Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff, 30th October 2014

Directed by Deborah Light

Devised with and performed by Eddie Ladd and Gwyn Emberton

Sound by Siôn Orgon

Costumes by Neil Davies

The making of the work

Before I saw this show I talked to Deborah Light, Eddie Ladd and Gwyn Emberton about the genesis of CAITLIN. Eddie was commissioned by the National Library of Wales to create a work as part of the Dylan Thomas centenary celebrations. There were just two stipulations – the work was to be about Dylan’s wife Caitlin, and it was to be a dance piece. Originally Eddie thought of it being film, but it evolved to be a performance duet, directed by Deborah and developed organically with Gwyn in the role of Dylan, and also with Siôn Orgon who made the soundtrack. The work was premièred in July 2014 in the Gregynog Gallery at the National Library in Aberystwyth. The form of that Gallery, an intimate space with a lot of things in it, in particular a large number of chairs, had a profound influence of the shape and nature of the work which the three dance artists devised. I did not ask more – I would shortly find out!

Caitlin and Dylan were married for over sixteen years, until his death in 1953, and this work is about the nature of their life together, which was marked by a mutual dependence on alcohol and on one another. I asked Deborah whether this work, like HIDE and much of her earlier work, was about what is revealed and concealed. She said that CAITLIN is, rather, a narrative piece and that what she has done in directing it is to start with a focus on tone, which is primarily bleak. The work has been conceived to offer a perspective on the relationship between Caitlin and Dylan in which their co-dependency is highlighted.

I commented on the irony of setting the piece in an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting, a structure intended primarily for talking. In fact there is speech in the piece, but Dylan says only two words. The team decided it would have been too difficult for Gwyn to reproduce the so-well-known cadences of Dylan’s speech, and this would also have been a distraction from Caitlin, who is at the centre of the work. Movement has of course its own language, and Deborah has worked with the performers on a vocabulary of movement in CAITLIN which relates specifically both to the Caitlin/Dylan relationship and to Eddie and Gwyn playing them. She said that she had started the work of developing the choreography not from words but with physical tasks – for Gwyn working with the head, because of Dylan’s focus on his brain; for Eddie more from her centre, because Caitlin lived more in her body, having trained as a dancer in her youth.

The Performance

The audience enter a room in which there is a circle of folding chairs. We are invited to hang up our coats and sit anywhere in the circle within a prescribed pattern, leaving many empty chairs. There is no ‘theatrical’ lighting. A woman enters. She is dressed neatly, demurely. She sits in place where she has empty chairs on her either side, looks around with determined caution, takes a breath and says, to the circle,

Hello, I’m Caitlin and I’m an alcoholic.

A man on the opposite side of the circle immediately stands and walks across the room saying:

Hello Caitlin.

He falls to his knees and puts his head in her lap.

The woman tells us that her husband was a very famous poet and that she was going to be a very famous dancer.

I thought it was going to a truce between his brains and my body.

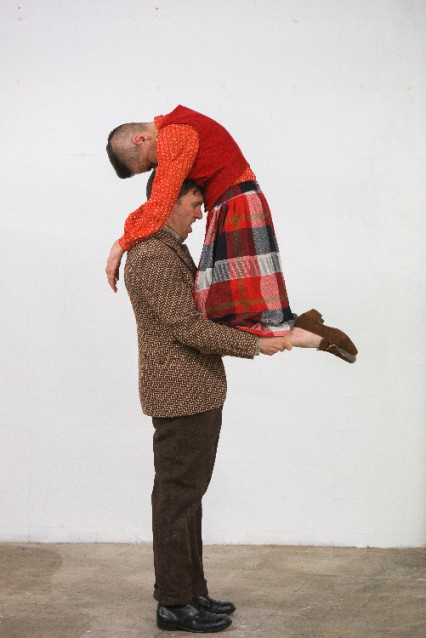

Thus begins a dance duet which moves through the shared life of the two characters, in which they literally fall for one another, over and over again. In a defining image from the piece Dylan carries Caitlin wrapped round his neck, her torso covering his face. That image conveys vulnerability and tenderness, but shows from the start that the equal relationship which Caitlin had hoped for was not to be.

If as watchers in the circle we are ever tempted to romanticise the relationship between Caitlin and Dylan, as they move in briefly joyful unison or we glimpse a moment in which a head rests on a shoulder, we are quickly brought back to reality as they bounce off one another and fall, time and again, to the hard floor.

Caitlin’s words, used sparingly but tellingly to spotlight turning points in the relationship, act as punctuation marks in the dance through the blurring miasma of alcohol, which might otherwise bring everything to confusion. And then there are the chairs, which populate the piece, not with more characters, but with metaphor, structure and weight. When Caitlin tells us:

We had three babies. Well, I had four, my husband was a professional baby.

She rocks a chair, folded and lying on the ground, like a cradle. Meanwhile Dylan sits inside another upturned chair, helpless as a baby. Caitlin gives him a book and sweets and he circles round in his own internal world while she busies around doing all that a mother must do. Siôn Orgon’s soundtrack, which mixes music from a score by Thighpaulsandra, contributes to the relentlessness of that grinding routine, one to which Dylan appears happily oblivious.

The narrative is not linear. After all, by the time Caitlin went to an AA meeting it was twenty years after Dylan’s death, so why would should she recount things in chronological order? It is partway through this narrative that we see what happened when she visited Dylan in his hospital bed in New York just days before his death. And it is not the ‘performance’ which she reportedly put on which we see, but the chair which acts as the straitjacket in which she was taken away to Bellevue Mental Hospital.

Then we are back to earlier days when the bond between Caitlin and Dylan kept them together in spite of infidelities, in spite of the effects of the drink which they take together like fooling clowns. Together they fight, they nuzzle, they entwine. When they pull apart he is loose-limbed, head pulling him; she is driven, ever on the move. The chairs are, by turn, refuge, containment, burden. They are also, in their crashing on the bare floor in the echoing room, the ‘noise’ of the pair’s deteriorating relationship.

The contribution of Siôn Orgon’s brilliantly diverse soundtrack to the whole piece could too easily be overlooked, so well does it run with the drama. There are, for example, two occasions where a tolling bell underscores the way Caitlin is – admittedly of her own volition – entrapped in this downward spiral. Again the chairs are wonderfully well used. It is no less than extraordinary to see Caitlin lift eight chairs together and lie with them all on top of her, and then to see Dylan turn into the caring parent animal who flings the chairs aside, nudges her up and, taking the material of her clothes in his mouth, lifts her to the ‘safety’ of sitting on a chair.

If what we see is a fall from grace there is nonetheless a kind of grace in the enthralling energy of this work, a committed portrayal of a relationship which starts in turmoil and proceeds to destruction. At the end Dylan is astride stacked chairs while Caitlin continues to carry the burden of chairs on her back, until both crash to the ground one last time. It is Caitlin who manages to stand up, go to a chair, sit once more and say, to the room,

I’m Caitlin and I’m an alcoholic. Thank you for listening.

It is a wonderful, movingly truthful ending to a peerless and revelatory performance.

Photo’s Courtesy of Warren Orchard

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.