Phil Morris discusses the career of the Welsh screen actor Ray Milland, whose films are being shown at the Chapter Arts Centre.

Ray Milland was an actor who regularly confounded expectations. While he lacked the rugged charisma, rich baritone voice and raw talent of his fellow countrymen Richard Burton and Anthony Hopkins, the Neath-born Milland was the first Welshman to win an Oscar. In terms of its length and breadth his Hollywood career has few parallels, encompassing; screwball comedy We’re Not Dressing (1934), epic adventure Reap the Wild Wind (1942), a Hitchcock thriller Dial M for Murder (1954), a global blockbuster Love Story (1970) and even a small role in sci-fi mini-series Battlestar Galactica (1978). Milland neither trained as an actor, nor had any prior theatrical experience, like his contemporary David Niven he spent several years in the British Army as a cavalry officer before bluffing his way into American movies with his good looks and easy charm. Unlike a host of handsome young leading men of the 1930s who faded from the screen Milland endured, extending his range as a character actor, star of B-movies and occasional director.

The highlight of his career is undoubtedly his Oscar-winning turn as alcoholic writer Don Birnam in Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945). The film shocked many with its searing look at alcoholism, Milland’s wholly convincing performance was rooted in pre method-era research he undertook at sanatoriums and drunk tanks. For an American audience coming to terms with the emotional fall-out of the Second World War, Don Birnam’s psychological torment, as addict and burn-out, was a case that many found sadly familiar and truthful. The film stands up well today mainly because of the sensitivity with which Milland played this career-defining role, revealing the aching vulnerability that drives the character toward self-destruction.

The critical and commercial success of The Lost Weekend did not pave the way for Milland to become a huge star, though he was briefly Paramount Studios’ highest-paid actor. The emergence of younger, more virile stars such as Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster, and method actors like Montgomery Clift (and later Marlon Brando) began to eclipse the aging Welshman, whose sophistication and refined looks seemed to belong to another era. Yet Milland kept working; the roles became less high-profile but they were arguably more quirky and interesting.

At the core of Chapter’s commendably eclectic and smartly curated season are a pair of films that Milland made with B-movie auteur Roger Corman, The Premature Burial (1962) and X: The Man With X-Ray Eyes (1963). Corman’s films of the early sixties, particularly his Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, gained instant cult status and grudging critical acclaim, mostly due to the director’s legendary ability to extract silk purse production values from sow’s ear budgets, and his casting of distinguished actors who could lend a distinct touch of class to rather workmanlike scripts. Whereas the likes of Vincent Price and Boris Karloff coupled their other-worldly strangeness with a campy gravitas that was entirely appropriate to Corman’s lurid takes on Poe’s gothic stylings; Milland brought something altogether different to the role of doomed artist Guy Carrell in The Premature Burial. His performance is an unsettling portrayal of a subtle and neurotic intelligence gradually devouring itself beneath a thinning veneer of urbane sophistication.

The Premature Burial, like the best horror films, is concerned less with the object of fear than the dynamics of fear itself. Poe’s original short story is a characteristically acute psychological study of obsessive fear, specifically the prevalent 19th century terror of being buried alive. The film frames Carrell’s mental collapse within a sketchy and unconvincing murder plot, in which his too-good-to-be-true wife, Emily, turns out to be too good to be true. A series of incidents, designed by Emily to play upon her husband’s fear of an inherited medical condition, lead to Carrell being buried alive after he is shocked into a cataleptic state. The attempted murder is foiled unwittingly by Emily’s father, who orders his dead son-in-law to be exhumed for medical experiments within hours of the funeral. The tropes of Poe’s gothic fiction; family curses, faded aristocratic ruin, murderous obsession and insanity are therefore all present and correct, yet the attempt by screenwriters Charles Beaumont and Ray Russell to open up their source material somehow falls flat.

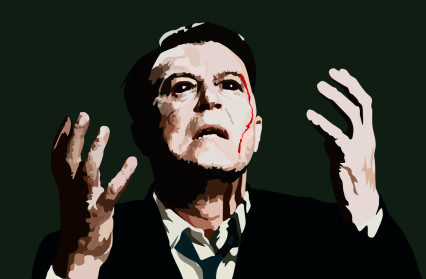

The thick fog that appears to perennially swamp Carrell’s large country estate, is a metaphor for the character’s creeping mortal dread. The cinematography by Corman veteran Floyd Crosby is vivid and glossy but serves only to hide the limitations of the production budget. An expressionistic dream sequence is heavy with colour filters but somewhat light on the atmospherics of terror. So it falls to Milland to provide the film with its nervy palpitating heart and its deranged finale of brutal revenge. The dominating image of The Premature Burial is not the rich palette of Panavision colour but Ray Milland’s eyes, which communicate the helplessness and inner-tumult of his growing paranoia with an intensity similar to that of his ground-breaking depiction of alcoholism in The Lost Weekend. The stomach churns in sympathy at his sickened expression when a mewing cat is discovered trapped between a wooden panel and a wall. In the film’s climactic burial scene, during which his character is locked inside a self-induced paralysis, Milland is able to convey the absolute horror of being declared dead and buried alive with an unmoving stare, which is as compelling a visual representation of Poe’s morbidity as you are likely to find anywhere on film.

The image clearly made an indelible impression on Corman because he cast Milland in X: The Man WithX-Ray Eyes the very next year. This odd curate’s egg of a film was made with the same crew that made The Premature Burial, yet its feel and look belong very much to Cold War America, with its theme of scientists playing God with technologies they cannot control. Milland plays Dr James Xavier, a research scientist experimenting with an eye-drop solution that can extend the range of human vision. Frustrated by the limitations of trialling the drops on animals, and by being ‘blind to all but one-tenth of the universe’ he experiments on himself, with predictably disastrous results. Initially, Xavier’s newly acquired power of X-Ray vision enables him to cure a cancer-stricken young girl, but the extension of sight brings about profound psychological changes in him and he winds up as a fugitive from the authorities.

The early hospital scenes in X: The Man With X-Ray Eyes are unintentionally humorous, played with an earnest hand-wringing-in-the-face-of-bizarre-situations-manner redolent of Channel 4 comedy Garth Marenghi’s Dark Place. Milland’s unaffected air of intelligence might have been perfectly suited to his role of doctor-gone-mad were it not for the cringe-worthy dialogue he often has to deliver. The film lurches wildly from sci-fi fantasy to melodrama to cack-handed social satire with Milland straining to hold everything together, until that is both the narrative and central performance make a final bold turn into abstruse mysticism.

On the run, abetted by a long-suffering girlfriend, Xavier is asked what it is exactly that he sees from his getaway car. He delivers a strange, almost poetic, apocalyptic meditation on the post-War American city – it is a moment that jars dramatically with the earlier tone of the film:

‘Rising into the sky with fingers of metal. Limbs without flesh. Girders without stone. Signs hanging without support. Wires dangling and swaying without poles. A city unborn. Flesh dissolved in an acid of light.’

A playful, though often silly, disquisition on the metaphysics of sight is suddenly transformed into a mysterious fable, in which Xavier’s penetrating vision looks out beyond our world of phenomena into the noumenal realm. The author Stephen King has observed of the film’s biblical ending – which takes place in a preacher’s tent in the Nevadan desert – that it is reminiscent of the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft, and by extension the Welsh writer Arthur Machen. Milland’s closing speech certainly draws on a vein of mystical wonderment:

‘I’m come to tell you what I see. There are great darknesses – farther than time itself, and beyond that darkness a light that glows, changes. And, in the centre of the universe, the eye that sees us all.’

It is a hauntingly bizarre final scene that closes with Xavier gouging out his own eyes for having the temerity to have glimpsed only what God should see. It is a rare breed of actor that can succeed, as Milland does, in giving the climax of this quite frankly bonkers film some sense of tragic grandeur. The B-movie directors of post-War cinema were extremely fortunate in having at their disposal a number of actors – including Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee in the Hammer stable – who imbued each of their performances with an emotional intensity and seriousness of purpose that occasionally elevated their material from the merely sensational and exploitative to the near-profound.

With the obvious exception of The Lost Weekend, Chapter’s season of Ray Milland films does not showcase the work of Ray Milland at his very best. Wilder’s earlier comedy The Major and the Minor (1942), Fritz Lang’s Ministry of Fear (1944) and the self-directed psychological Western A Man Alone (1955) are better examples of Milland’s underrated talents. In the Corman films we see a fine actor struggle with material that is clearly beneath him but to which he never condescends. Indeed, a through-line can be drawn from The Lost Weekend to The Premature Burial and X: The Man With X-Ray Eyes, as each of these films feature an anti-hero who has gazed into the abyss only to be destroyed when the abyss gazed back at him. Milland is a not a name that springs to mind when you think of Welsh acting greats, but his eyes were those of a consummate screen actor.

To find out more about upcoming events at the Chapter Arts Centre visit their website.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Original illustration by Dean Lewis