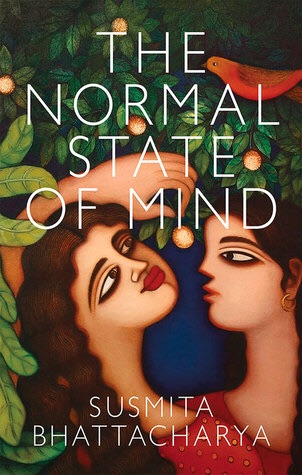

Justin Jones casts a critical eye over Susmita Bhattacharya’s novel The Normal State of Mind.

Susmita Bhattacharya’s novel may have been conceived in Plymouth and Cardiff, but it is set in Mumbai and Calcutta during the social convulsions of the 1990s.

Susmita Bhattacharya’s novel may have been conceived in Plymouth and Cardiff, but it is set in Mumbai and Calcutta during the social convulsions of the 1990s.

The blurb certainly makes it clear that while Bhattacharya tells the tale of two Indian women, there is a wider story here. She seems to aiming at writing something of a state of the nation novel in which Dipali and Moushumi, the two central characters, act as voices for disempowered women in the subcontinent. Obviously, one might be tempted to consider The Normal State of Mind to be a ‘lesbian story’. However, while same sex relationships play a central role in the novel, the book portrays wider issues concerning the lives of women in India, issues that continue to be painfully relevant in 2015. As Dipali says at one point, ‘a woman always has to lose’. And perhaps it’s not just women: the struggle of Moushumi and others like her is bound up with a wider class struggle in a country where ‘rich people’s SUVs ran over homeless people sleeping on the streets’.

The Normal State of Mind is a story of shifts in personal identity and orientation and it is set in a nation experiencing something similar: Moushumi is forced to move to Mumbai, a city that Bhattacharya tells us has reverted ‘back to the original name the natives used to call their city’. Moushumi recognises, however, that while there may be ‘different names’ and ‘different identities’, ‘the spirit of the city has not changed’, something her own family cannot understand about her after her lesbian identity is revealed. But it doesn’t matter to her: ‘she too would metamorphose’.

Indeed, this idea of metamorphosis is echoed in the repeated references to film, to actors, to story telling. So many Bollywood films begin on the steps of the Mumbai railway station where Moushumi finds herself after fleeing the family pressures placed upon her back home in Calcutta (or should that be Kolkata?). There is a point where Moushumi is changed in Dipali’s eyes into ‘a soft filtered heroine in a sixties Hindi film; she is ‘transformed into another being’. And yet, when the film trope makes its next appearance, it is very much the case that men are in charge of the stories being told in this medium, when a film poster is described as featuring a ‘buxom woman clad in a wet white sari…(who) leaned against a man with a bushy moustache and broad shoulders’. The portrayal of women is fiercely contested here: a group of women protest against the soft core pornography on offer in this scene, while later on, a Hindi film that dares to tell a ‘lesbian story’ is met with an extreme violent response. As one outraged man says, it’s ‘not Indian culture, spoiling our sanskriti.’ When Moushumi attempts to honestly tell her story to the media, defending the women who protest against the violence displayed against this film, she suffers for it.

The portrayal and the silencing of women shape and influence much of the novel. Gandharv is the photographer with whom Dipali has a relationship after the death of her husband. He seems to be a new generation metrosexual Indian male but it’s interesting how his role as a photographer is emphasised; one could argue that he profits from the ‘male gaze’ as he takes pictures of ‘Miss Mumbai’ for an advertising shoot. In a very different way, when Dipali’s brother attempts to take control of the family’s assets, he asks her ‘And since when have you grown a tongue?’ Later, Dipali thinks of the physical and sexual contact she had with her long dead husband and how easily her brother ‘made it sound filthy’.

While Bhattacharya attempts to paint on a broad canvas, the book itself reads very easily indeed. The narrative and the characters’ dialogue are very snappy and accessible. Indeed, it seems as European readers that we are being tempted to think of these characters as living in an India that is becoming easily and rapidly Westernised. However, the novel is full of Hindi terms and phrases which aren’t translated: a bride’s eyes are ‘covered in paan leaves’, children gorge themselves on ‘jamuns’, a restaurant serves ‘good brun pav chai special and kareema parathas’, some of the characters have a view which overlooks ‘the tops of the Gulmohar trees’. There is a sense that the women in the novel are cutting across the grain of a venerable culture; their lives are ones of tremendous difficulty, despite the ease with which their story is told. Despite the easily accessible style of the book, we are reminded that India itself is an enormous and enormously old culture; when Moushumi tells her lover Jasmine that lesbian relationships are accepted in the West, Jasmine tells her to ‘go live in the West’. However, perhaps the deeper roots of Indian culture are being forgotten by some of the reactionary characters that Bhattacharya portrays. The shape shifting supreme god Krishna appears on several occasions in a book of shifting identities while Moushumi reminds a journalist who interviews her about the Kamasutra and how ‘homosexuality existed then and it exists now’.

Those very culturally specific references in the novel are often focused upon the sensual impact of new sights, new tastes and textures. Moushumi meets her socialite lover, Jasmine, at an art show; their first kiss is compared to the ‘confusion of pleasure and pain’ that accompanied the memory of a childhood feast. Indeed, descriptions of heady tastes and sensations infuse the book, the newness or unfamiliarity of them to European readers perhaps echoing the new sexual and emotional sensations being experienced by Moushumi and Dipali.

This sense of the book being perhaps not quite the easy read that one might have initially expected can also be seen in the structure of the novel. The first section, set in 1990, contains alternating chapters from the viewpoints of the central characters, outlining Moushumi’s experience as a lesbian who is ostracised by her family and Dipali’s life as a young bride who is about to experience terrible personal tragedy. Each chapter is entitled ‘Moushumi’ or ‘Dipali’. When the story jumps forward to 1998 in the second section, the chapter titles are abandoned as the two threads of the story become entwined and Moushumi and Dipali end up working in the same school. It seems as if Bhattacharya is telegraphing to the reader an eventual relationship that is bound to blossom between the two women. However, without wanting to put you on spoiler alert, things aren’t as simple as that.

They discover a common bond, a common experience as they start to work together as teachers at a Mumbai convent school. While Moushumi introduces new tastes and ideas to Dipali, Dipali sees in her at one point not a lesbian but ‘a vulnerable woman with tears in her eyes’. Indeed, this common bond is emphasised when Dipali observes that they are similar because widows and lesbians are both ‘hanging on to the edges of society, begging to be recognised’. There is a wider battle being fought here.

At its best, the strongly sensual descriptions of the streets of Mumbai and of new tastes and sensations leave a lasting impression in the mind while that ‘snappy dialogue’ really does catch the rhythm of everyday conversation. And despite the brisk style of the novel, it is genuinely moving at many points. Dipali’s experience as a young widow, her terrible sense of isolation and entrapment, has a powerful effect on the reader. Moushumi’s exile from her family is also poignantly portrayed, especially when her nephew answers when she tries to phone home and he is told by someone in the background that ‘You mustn’t talk to strangers’ before they hang up.

At other times, the worthiness of the novel’s subject matter grates somewhat as it affects the style of the writing; occasionally, there is perhaps a little too much ‘tell’ and perhaps not enough ‘show’. However, A Normal State of Mind is a powerful debut novel and is a very encouraging sign of future things to come from Bhattacharya. Its publication by Parthian is also another welcome confirmation of how wide ranging and cosmopolitan the publishing world in Wales can be.

The Normal State of Mind is available from Parthian Books.

Justin Jones is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.