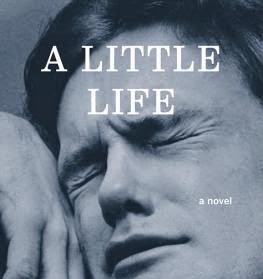

Carolyn Percy casts a critical eye over A Little Life, the new novel from Booker-shortlisted author Hanya Yangihara.

Four very different individuals meet at a small Massachusetts college – mercurial JB, dependable Malcolm, kind and handsome Willem and the brilliant but reserved Jude – and find, in each other, that rarest thing of all: pure and perfect friendship. After graduation they all head to New York to pursue their dreams of adult life: JB as an artist, Malcolm an architect, Willem an actor and Jude a litigator. The path to success, however, is not always smooth, and as relationships morph and mutate over the years, they come to realise that it won’t be their careers that are their greatest challenge but Jude himself. Jude, whose brilliant mind pulls people into its orbit like planets, but whose past remains as mysterious to them as the contents of a Chinese box; outwardly a confident and ferociously talented litigator, inwardly an ever more broken man. For Jude’s whole life is dogged by a shadow, the events of an inexpressibly cruel and terrible childhood that have left him scarred both in body and mind.

Finishing Hanya Yanagihara’s Booker-shortlisted second novel is an experience akin to being put through an emotional mangle, which, I’m aware, doesn’t sound like much of a recommendation, but, trust me, it is. A Little Life is a book of many facets. It begins as a tale of four friends trying to make it through life in New York before peeling back the layers to reveal the real story, that of Jude, a gothic Dickensian fairy-tale of abuse and trauma. What makes it work is, partly, the way the story is constructed: told from multiple viewpoints, this allows the facts about Jude’s past to be revealed piecemeal, ensuring a gradual build-up of tension and emotion rather than a tidal wave that overwhelms the reader. Some have complained that the level of abuse depicted in the novel is unrealistic and gratuitous. Is it? Well, as far as unrealistic goes, it depends on your opinion. We know that, unfortunately, institutionalised abuse does happen, and that isolated abusers also exist, and Yanagihara herself admits – in an interview with the Guardian on July 26th – that she “wanted there to be something too much about the violence in the book, but I also wanted there to be an exaggeration of everything, an exaggeration of love, of empathy, of pity, of horror. I wanted everything turned up a little too high.” As for gratuitous, I have to disagree. The events in A Little Life may veer into melodramatic territory but the prose certainly does not; it’s beautifully precise and psychologically deft. So psychologically deft in fact, that one of the things that left me feeling unsettled weren’t the descriptions of abuse and self harm but the fact that she manages to write about self-harm in a way that manages to take you completely into the mind of someone who self-harms and make you understand – even empathise with – their motives and logic. But where there is darkness there is also light, for A Little Life is also a paean to friendship, particularly male friendship, something that’s often side-lined in fiction in favour of romantic relationships. Willem, in fact, makes an interesting point, when he muses on society’s apparent obsession with seeing people settle down in couples, citing ‘“thousands of years of social evolution and this is still our only option?”’

But even though there is as much love and kindness as there is darkness, A Little Life, rather bravely, shows that, sometimes, no amount of love is a miraculous cure for pain, and that some things can’t be ‘fixed’, and so it comes to a rather sad end, somewhat inevitably but still managing, simultaneously, to pack a punch to the gut and contain a small, bittersweet seed of hope.

Yes, the subject matter is difficult. Yes, I felt a little like a wrung-out sponge when I’d finished it. But my God, it is satisfying. A dark and heart-breakingly beautiful novel that well deserves to make the Booker shortlist

A Little Life is available from Penguin Random House.

Carolyn Percy is a critic and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.