Historian Peter Wakelin explores the fact and fiction of the post-Brexit prediction and outlines the likely pathways of a Europe and Britain severed.

The historian in me has always been interested in counterfactuals, those thought-experiments in which you try to assess the significance of one entity or event from the past by imagining what the rest of history would have been like without it. For example, if the railway hadn’t been invented, would the USA ever have become a great power; would Britain have been much different if Edward VIII had held onto his Crown? A few years ago, I was deeply intrigued by reading Philip Roth’s speculations in The Plot Against America, in which Roosevelt is beaten to the Presidency in 1940 by the aviator Charles Lindburgh, who thinks Hitler a great man and keeps the USA out of World War II.

So naturally, I’m curious about the alternatives on our horizon in 2016. Just what would the world look like under a Trump presidency? And what would happen if we really did leave the European Union? It’s a great game to play: picturing the parallel universe in which these things actually happen.

Let’s leave Trump out of the picture for now. Here’s how I see it if we Brexit.

First, the almost unbearable aggression of the referendum campaign is magnified yet further by recrimination and division. Britain is torn into two groups, each with deeply-felt and mutually exclusive world-views: internationalists on one side, horrified at finding themselves in a country they no longer recognise, and on the other triumphalist Englanders. A country once world-renowned for tolerance suddenly becomes a byword for civil strife. The fault-lines make the break-up of the UK inevitable: another referendum takes Scotland out of the UK; violence erupts on the streets of Belfast amid calls to reunify Ireland. Wales tries for independence but finds no majority for it.

In the new England and Wales, Metropolitan interests create an economy fit only to high finance, and a society fit only to the wealthy. Wales and parts of England grow weak and poor. The promised land of the Brexiteers – a place of low immigration and prosperity through free trade – both prove illusory. No longer the Workshop of the World, Britain discovers the impossibility of competing with countries that, unlike its old EU trade partners, unsportingly undercut its costs and standards. Illegal immigration soars without a partnership of neighbours to control refugees as economic migrants are still desperate to get to Britain for its one remaining virtue, that it speaks American. Bodies pile up on North Sea and Bristol Channel beaches now.

There’s a dramatic impact of Brexit on the rest of Europe, too, conditioned by the instability brought on already by the refugee crisis, austerity and readjustment to new world economic powers. The oxygen of Britain having done the unthinkable makes the flame of dissatisfaction throughout Europe burn brighter. Nationalism and racism flare. It starts with electoral wins by the Freedom Party in Austria and Marine Le Pen in France, then Kaczynski pushes Poland further to the religious right. Structures of democracy on which the European Union is founded totter, and EU members crash out until none is left (fulfilling the avowed wish of some Brexiteers).

Hate, selfishness, xenophobia, nationalism, ignorance, underlie all of this instability. They are the reasons Europe needed international cooperation and now they rise again, like rats from under the floorboards. Putin is emboldened to test the weaknesses of Western treaties. He begins by annexing the parts of the Ukraine he hasn’t grabbed already. Soon Russian forces seem to threaten Estonia, where the government elects to resign from NATO rather than spark a continental war.

Is this pessimistic? I wish such possibilities couldn’t come to pass, but I think there’s every risk they would. And they would be irreversible. In Philip Roth’s counterfactual America, the dark episode of anti-Semitism and authoritarianism comes to a close and everything returns to its true trajectory in the end with Roosevelt’s re-election. But I fear that all King Charles III’s horses and all of his men couldn’t put Europe together again.

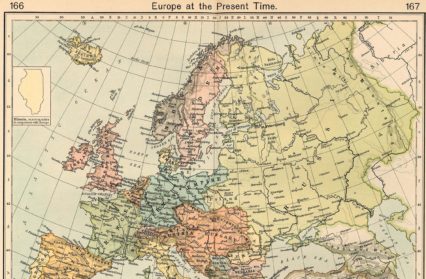

Addressing these possibilities makes me realise that what’s at stake is not just red-tape about vacuum cleaners, nor even the number of Poles in Peterborough. We are putting at risk the triumphant achievement of two generations of peace and cooperation in what was ever previously, the most intensively contested place on earth. My parents and my grandparents had to go to war, and I’m intensely grateful to belong to the first ever European generation to escape it. Yes, NATO has been a peacemaker, but history shows that nations make and break military treaties as easily as sneeze. The European Union made peace real not through snatched political alliances but through fostering deep relationships, in trade, movement of people, collaborations, partnerships, marriages. For now, these make it inconceivable that we would go to war with one another.

I share emotions with the Brexiteers. How lovely it might be to walk away from complex problems such as demographic pressures, budget cuts and tricky regulations. As individuals, any of us can find it satisfying to resign from organisations, or break collaborations, or abandon spouses and families, and just say, ‘I’ll decide for myself’ or respond, like Cain, ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’ Yet as individuals we know deep down that problems aren’t all caused by our relationships and we can see that we’re weaker and less capable if we try to do things on our own. The same must be true of nations, all the more so in an inescapably interdependent globe. Britain will succeed by working for a smarter, better Europe, not by abandoning it.

This imagining of outcomes quickly stops being entertaining. As the madness suddenly seems really, truly, possible, and already violence and lies are poisoning our society, please let the thought-experiment be enough.