Welcome to Wales Arts Review‘s look back on the cultural highlights of 2016, a tour of the moments that have lifted up the year for some of our top writers and artists.

Sophie McKeand

The highlight of 2016 for me in Wales was Focus Wales festival. It’s been gaining in style and confidence since its inception five years ago and has quickly become an absolute calendar-must. Held across multiple venues in Wrexham over four days in May, Focus Wales showcases some of Wales’ most innovative and interesting performers on a platform that’s becoming increasingly international. My only complaint is that, now it’s getting bigger there just isn’t the capacity in the time/space continuum to see everything, no matter how hard I try, or how much gin is consumed.

Every year I have a new art-crush. This time around New Orleans based Charm Taylor blew me away with her unique blend of spoken-word-freestyling-soul-sonic-magic. And she looked great doing it while being deftly supported on synth by Amahl Abdul-Khaliq (aka Af the Naysayer).

These international exchanges are a real high-point. In the past Focus invited artists over perform from South Korea who completely shredded our minds – that year was off-the-wall-manic-to-the-point-of-insane and we loved every crazy band.

You might feel that having to leg it around town to see all the artists when, to be honest you still won’t see every band marked off on your programme, is asking a bit much, especially now that some of the venues are starting to hit capacity but what gives a festival like this its charm is the multi-venue element. A day that begins sitting in hushed pews in St Giles’ Church watching a stunning acoustic performance from The Gentle Good, that continues with hot-footing it over to Oriel Wrexham to catch Voicebox spoken word collective, that later involves legging it to Central Station to be sonically battered by Qujaku (from Japan) is a good day indeed. It’s a time when Wrexham comes alive that’s not about football or the usual Saturday night blag.

People are finally making the effort to travel here for the festival, which has taken a while because there’s an odd cultural identity in this old town: not Welsh enough for the north-west Walians, too provincial and northern for Cardiff, too Welsh for Liverpool or Manchester, too working-class for Chester, which has, in the past, created a certain kind of cultural psychosis, a ‘why should we bother when this town is shit’ local attitude.

The arts scene here has made a huge difference to the wider world’s perceptions of Wrexham, and helped local young people begin to take a real interest in the town’s creative endeavours instead of feeling they need to up-and-leave to find anything culturally interesting. I believe Wrexham has the potential to be a real northern powerhouse in Wales, in the way Manchester is for England, and it’s cultural pioneers like Focus Wales who are forging an interesting path forward.

Sophie McKeand is the Young Persons’ Laureate of Wales, and in January 2017 will be Wales Arts Review’s Artist in Residence.

Niall Griffiths

The highlight of 2016 will be the very second the clock ticks over into 2017 and I can wave goodbye to this vile, stinking, obscene year. The deaths of heroes; the deaths of friends very dear to me; the slipping back into barbarity of many people with the realisation that to think, and to feel, are far too difficult, and life is far easier with the painless and stupid joys of obedience, especially when wearing the tissue-thin mask of rebellion. 2016 – the centenary of the Somme, and oh how keen we’ve been this year to re-enact the senseless slaughter of that. The year when lies became truths; when compassion became a weakness to be eradicated; when to question became taboo; when the dumb bellow drowned out reason. This year will be the year that future historians will point to and say ‘that’s where the horror began again; that’s where the rotten-ness ran out of all control’. 2017 will be worse, but when 11:59 becomes 00:00 there will be a tiny moment of futile hope, a moth’s breath of optimism, an at least miniscule instant in which the thought ‘maybe everything will turn out okay’ will not seem laughable. Fuck this year.

Oh, and Wales reaching the semi-final. Obvs.

Niall Griffiths is author of 9 novels, and his first poetry collection, Red Roar: 20 Years of Words is available now from Wrecking Ball Press.

Robert Minhinnick

During my interview with John Barnie in October/November 2016, recently published by New Welsh Review and Sustainable Wales, what was confirmed for me was this man’s dedication to writing. And above all, his dedication to poetry.

Barnie appears to maintain a rigorous regime, rising at 6am and starting work at 7am. Often, he states, this work is fruitless, yet I must contradict him. John Barnie has published over 300 poems, plus memoir, reviews and a cohesive collection of essays {‘Fire Drill’}, since his Selected Poems appeared from Seren in 2006.

Barnie appears to maintain a rigorous regime, rising at 6am and starting work at 7am. Often, he states, this work is fruitless, yet I must contradict him. John Barnie has published over 300 poems, plus memoir, reviews and a cohesive collection of essays {‘Fire Drill’}, since his Selected Poems appeared from Seren in 2006.

The process of this interview was certainly good for me, as I rediscovered a man dedicated to art, atheism and the importance of science. (Barnie’s latest poetry derives from his residency in Oxford university and looks exciting…}

Yes, there is John Barnie on these black and frostbitten mornings hunkering down yet squaring up in Comins Coch and actively pursuing poetry’s holy smoke.

Barnie’s thinking bout ‘time’ permeates his published poetry with an awareness of geology and the ‘fossil record’. This indeed is his great subject, allowing him the longest perspective of all ‘non-religious’ poets.

Yet more recent time takes centre-stage in Wind Playing with a Man’s Hat (Cinnamon, 2016) with its writing about ’death’ and ‘the old’.

Chastening? Maybe. Yet deliciously acerbic in their refusal to sentimentalise. At least that’s how I find many of the poems in this book, paying as I do regular calls to care homes and locked wards.

Many of the tiny poems such as Barnie has published since that Selected are like the hard bitter lemons I remember from childhood. Compulsive, addictive.

Although he dislikes social media, John Barnie cannot be technically maladroit, having edited ‘Planet: the Welsh Internationalist’ for many years. But because of his lack of Facebook etc. presence he has no immediate on-line constituency that might in theory buy, or even read, his books.

But for John Barnie social media, with its self-promoters and hyperventilating local demagogues, offers a miasma of possibilities he has decided to abjure.

Are there better poets? There always are. But I really cannot think of a better poet as role model, concerning him/herself with what’s important. And that is why I am glad to choose John Barnie’s publication of Wind Playing with a Man’s Hat as my Wales Arts Review’s highlight of the year.

Robert Minhinnick‘s latest novel, Limestone Man, is available now.

Mark Blayney

This being a year of things falling apart, it seems appropriate to try to glue them back together with inspiring lines I’ve heard individual authors say this year. ‘There’s a myth that readers read to escape things,’ Marlon James said at Hay. ‘Actually, it’s where they confront them.’ James, who won last year’s Man Booker Prize for A Brief History of Seven Killings, made the audience laugh for much of his 45 minutes with statements like ‘enjoying a book does not mean having fun’ and impeccable advice like ‘complicate your characters. Don’t make it too easy for the reader.’

Along the wooden duckboards to a different tent and Horatio Clare is amiably nailing the difference between a good book and a great book. ‘The subject is half the battle. The form is the pleasure.’ And elsewhere, Andrew Davies talks about sex, because people always ask him about sex. ‘It has to be on the spine of the story.’ So in adapting House of Cards, Mattie has to have an affair with the main character, not a secondary one as happens in the book. ‘This puts you in the difficult situation of realising – she’s going to have to have sex with the old man.’ Awkward face. ‘Dare I write that? In the end, I had to dare.’ On the page, Davies is as brave a writer as any, although there are limits. ‘I’m not allowed to talk about what I think of the remake,’ he said drily. ‘They actually put that in the contract.’

Along the wooden duckboards to a different tent and Horatio Clare is amiably nailing the difference between a good book and a great book. ‘The subject is half the battle. The form is the pleasure.’ And elsewhere, Andrew Davies talks about sex, because people always ask him about sex. ‘It has to be on the spine of the story.’ So in adapting House of Cards, Mattie has to have an affair with the main character, not a secondary one as happens in the book. ‘This puts you in the difficult situation of realising – she’s going to have to have sex with the old man.’ Awkward face. ‘Dare I write that? In the end, I had to dare.’ On the page, Davies is as brave a writer as any, although there are limits. ‘I’m not allowed to talk about what I think of the remake,’ he said drily. ‘They actually put that in the contract.’

My favourite moment was with Gillian Clarke, explaining why poems from the point of view of a child can seem so affecting. ‘The child doesn’t know something is sad. They just see it as interesting.’ Part of the joy of being a writer in Wales is the chance to meet and work with other writers you admire. We have a community here, a sense of belonging that is perhaps more pronounced than elsewhere. Hay symbolises this; a world-class festival in a place where you would have to be crazy to set up a festival (no train station for miles and it always rains). But, those clichés are as susceptible to investigation as others. This year it didn’t rain. When you get a cliché or myth (or even, shall we say, a lie on the side of a bus) it doesn’t take much to debunk it. The question is, when things fall apart, how best to glue them back again?

Mark Blayney is a short story writer and poet, whose latest collection, Loud Music Makes You Drive Faster, is out now.

Sian Norris

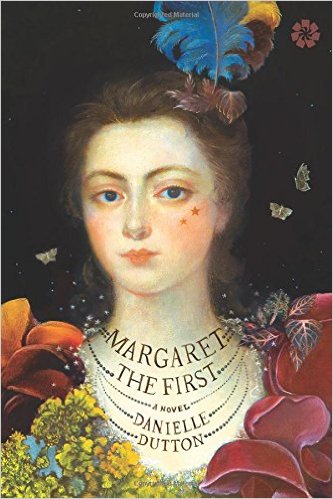

Margaret the First was one of the first books I read in 2016, when it was published in the USA by Danielle Dutton’s publishing imprint, The Dorothy Project. Looking back on a year that has seen the publication of many extraordinary works by tremendous women, it shines out as a gorgeous, fantastical highlight – written with Woolfe-ian fervour and vitality. Published in the UK this autumn, Dutton’s retelling of the life of essayist, playwright and proto-sci-fi writer Margaret Cavendish is a luscious read full of surprising detail and voluptuous imagery.

Dutton accomplishes quite a feat in fictionalizing Margaret’s entire life into a slim volume numbering 166 pages. We follow Margaret to Paris and Antwerp where she escapes the English Civil War; we witness her marriage with William the Duke of Newcastle, and then we journey back with her to the Restoration Court in London. It’s in London where Margaret becomes the ‘Mad Madge’ of legend – the ‘character’ Woolf writes about in her extended feminist essay A Room of One’s Own. Known for her daring and crazy antics, Margaret becomes a celebrity gazed upon in horror and wonder by the leading male minds of the day – male minds she dares to compete with on her own terms.

Dutton accomplishes quite a feat in fictionalizing Margaret’s entire life into a slim volume numbering 166 pages. We follow Margaret to Paris and Antwerp where she escapes the English Civil War; we witness her marriage with William the Duke of Newcastle, and then we journey back with her to the Restoration Court in London. It’s in London where Margaret becomes the ‘Mad Madge’ of legend – the ‘character’ Woolf writes about in her extended feminist essay A Room of One’s Own. Known for her daring and crazy antics, Margaret becomes a celebrity gazed upon in horror and wonder by the leading male minds of the day – male minds she dares to compete with on her own terms.

Writing a novel rather than straight biography gives Dutton the freedom to focus on the big, blazing moments of Margaret’s life, the interior world she inhabits as well as the external world in which she lived and produced her work, all interspersed with the domestic details that are the bread of life. Margaret the First is not—nor does it ever set out to be—a straight re-telling of Margaret’s history. Dutton takes a non-linear approach so that each big glowing moment of the novel shines on its own, and is allowed enough space and time so that the reader can relish the experience of reading Dutton’s pithy, poetic prose.

In Margaret the First, Dutton has written a remarkable book that gives us a joyous and minutely detailed insight into a female writer’s inner life. She brings to life in full colour, scent, and sound the history of one of our most remarkable and, sadly, forgotten women. A decidedly feminist novel, the thrill for the reader lies in Margaret’s lively inner voice, along with Dutton’s imaginative prose. Her writing is inventive and artful, conjuring a luminous, colourful and often grotesque world.

With Dutton’s novel, Margaret Cavendish will no longer be the woman Woolf described in A Room of One’s Own as the “crazy Duchess…a bogey to frighten clever girls with.” Instead, we discover an ambitious, hungry, and sensational woman who blazed and created and refused to be cowed by a society that saw her as an object of mere fun and gossip.

Sian Norris is a writer and feminist activist. She is the founder and director of the Bristol Women’s Literature Festival, and runs the feminist blog site, Crooked Rib. Sian will also be one of Wales Arts Review’s 2017 Artists in Residence.

Dan Tyte

It started with the dachshund. New year, new animal. One name enough, the sur superfluous. Patti, Leonard, Joni. The set texts of a youth that wasn’t mine but was lived in spite of the limits of space and time.

‘Iggy won’t work, you can’t call a sausage dog Iggy’.

So we didn’t.

*

We married in the spring. His voice stalked the rooftop scene, guttural and giving, the hands holding plates of picky bits not minding the drizzle, the mariachi band smoking, Spanish guitars slung over shoulders.

‘I’m going to break into your heart’

And she had.

*

She sprawled under the sheets, the blurred mascara black against the white of the bed. I left the apartment and crisscrossed the grid, Cinco de Mayo margaritas stale on my breath, the promise of the Lower East Side’s best bagel teasing me onwards. The rain seeped through the paper bag, the seeds showing, his voice in my ears.

‘You could be burned at the stake

For all your mistakes, mistakes, mistakes’

It was in my hands, all of it. It was possible, all of it.

*

The cats in the cafe in Le Marais ignored our table, preferring instead to play paw piano for a snap-happy family, the late summer sun breaking through the frame. A human mass snaked across the Seine to the festival field, wine bottles swaying by their sides. The buzz defied the Bataclan. He erupted onstage, 69 and day old naked.

‘Bonsoir mother fuckers’

It was a very good year, for Iggy and for us.

Dan Tyte is author of the novel, Half Plus Seven.

Emily Garside

The teenage Welsh Learner in me firstly wants to thank this production for a refresher in Welsh swear words – always a useful commodity. Secondly that long ago Welsh learner is also thankful for feeling this bilingual production was as much for me. Made inclusive not just through innovative use of video surtitles, but also through the attitude of the company, that their production that it was for everyone, no matter what language their native tongue, is an example for others to follow.

And, although language is a big part of this play, in terms of creating truly bilingual work, there’s much more to this play. The most important element of this play is, I’d argue, it’s heart (pardon the pun). What this play has is everything I ever want or need from theatre- a story that tells me something about people, and makes me feel something. As with many brilliant works the premise-as well as the staging is deceptively simple. For the premise, I believe writer Alun Saunders drew inspiration from the idea of ‘What if ‘Long Lost Family went really wrong?’ and following a boy from Wales who always knew he was adopted but didn’t know he had a brother, it does for a time go (hilariously and heartbreakingly) wrong. The idea of language dividing the two brothers, as an indicator of their different upbringings, is a fantastic device for storytelling but the inclusion of bilingual writing allows audiences to consider the way language shapes us, and how others see us. Staged on a virtually bare set, energetically almost frantically directed and brought to life with such (again pardon the pun) heart by its two young performers, there was something simply infectious about this production that makes it hard to shake in the best possible way.

And, although language is a big part of this play, in terms of creating truly bilingual work, there’s much more to this play. The most important element of this play is, I’d argue, it’s heart (pardon the pun). What this play has is everything I ever want or need from theatre- a story that tells me something about people, and makes me feel something. As with many brilliant works the premise-as well as the staging is deceptively simple. For the premise, I believe writer Alun Saunders drew inspiration from the idea of ‘What if ‘Long Lost Family went really wrong?’ and following a boy from Wales who always knew he was adopted but didn’t know he had a brother, it does for a time go (hilariously and heartbreakingly) wrong. The idea of language dividing the two brothers, as an indicator of their different upbringings, is a fantastic device for storytelling but the inclusion of bilingual writing allows audiences to consider the way language shapes us, and how others see us. Staged on a virtually bare set, energetically almost frantically directed and brought to life with such (again pardon the pun) heart by its two young performers, there was something simply infectious about this production that makes it hard to shake in the best possible way.

As a new theatre voice for Wales, and a new take on what Bilingual writing could be as well as simply being a beautifully written piece of theatre, A Good Clean Heart is one that will stay with me well beyond 2016.

That and how could you not love a play that has a Dizzy Rascal rap in Welsh?

Emily Garside is a widely published theatre critic and writer, whose PhD thesis was on theatre as a cultural response to HIV/AIDS.

The Afternoon Critic

My highlight was a great late Turner, Snow Storm – Steam-boat off a harbour’s mouth, making signals in Shallow Water, and going by the Lead. The author was in this storm on the night the Ariel left Harwich (1842) exhibited by the Glynn Vivian as part of an exhibition celebrating the life of Richard Glynn Vivian. I visited it four times and was sad to see it go. The gallery paid no special attention to it (even the title was abbreviated) but deserves praise for the excellent way it was actually displayed. Given its own space, here was an un-crowded, unhurried, opportunity to build a relationship with the picture as a visual experience and see if it still has the power to provoke the engagement of today’s viewers. If it does, it’s because Turner was one of the first to make art which addresses what have become the typical predicaments of artists and viewers experiencing modernisation: acceleration, instability, fragmentation, dislocation, individuation etc., with all their emotional and pathological effects. This was the sort of world that Turner experienced as coming into being. But to make art which served the new cultural needs of his audience, which includes us, he had to use what was to hand, existing traditions and genres, (dominated by landscape), and adapt them to serve needs for which they were not originally invented. Artists who provide this sort of cultural leadership face a perennial tension between sensing that their audience needs existing cultural practices to be elaborated, and audiences themselves, who may not yet see that these existing practices may be inadequate for objectifying their experience. Tuner’s Snowstorm, armed with its unlikely title, demonstrates the perennial difficulty for modern artists, of maintaining the attention of conservative audiences, in order to innovate and work against their ill-founded certainties.

Turner’s Snowstorm remains relevant because the painting achieves the aesthetic intensification required to give objective form to our personal and historical experience of life under conditions of modernity. To do this he had to change an aristocratic, religious, pre-modern way of seeing which, by using information about edges, surfaces and the spatial location of well-defined objects, tended to objectify stability and induce a feeling of calmness. Using the Snowstorm’s ‘transitional’ objects – storms, mist, spray, smoke, wind – objects certainly, but without stable surfaces, edges, or spatial location, Turner could make visible the energies and open-ended potentialities of processes, or change as it’s happening. Stability and calm are displaced by instability and uneasiness. If looking at a picture could make one sea-sick this might do it. The composition, lighting and handling of paint objectify the experience of being in a dangerous condition of high energy movement, rather than of location in space. The picture’s content is not about events or space. Turner intended his painting to upset viewers’ expectations just as the world which was coming into being was doing. But he tried to keep them ‘on board’ by kindly giving them a detailed narrative title so that they might mitigate their sense of insecurity by being able to say what was going on and where.

Watch this space for more cultural highlights from Wales Arts Review in the coming days.