Steph Power visited the BBC Hoddinott Hall in Cardiff twice for performances of Welsh Foundations and Great Brits by BBC National Orchestra of Wales.

It seems astonishing that the composers William Mathias (1934-92) and David Bedford (1937-2011) were born just three years apart – and that the same is true, two decades later, of Gareth Glyn (b. 1951) and Steve Martland (1954-2013). Greater musical contrasts would be hard to find across the UK classical music world of the last 80 years, and their proximity in time provides a fascinating glimpse of how diverse that world has been. Not that these pairings appeared together in the same concert but rather, differently aligned, within the same fortnight as part of the final instalments of two immensely worthwhile, parallel short series from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales: Welsh Foundations and Great Brits.

The series each explored a distinct musical strand bridging the 20th and 21st centuries: Welsh Foundations celebrated pillars of the burgeoning post-war Welsh establishment, and the composers building on that legacy today in Wales and further afield. Great Brits cast a wider geographical net to celebrate post-war and contemporary British composers who have pushed against convention by forging a strongly individual voice and new kinds of cross-disciplinary partnership. Appropriately enough, if just one were to be chosen, the sole Welsh composer featured in the latter, rebel series was Cardiff-based Charlie Barber (Great Brits 1, 13 January 2017); a longstanding, brilliantly accomplished defier of cultural barriers.

Of course it could be argued that the very founding of a music establishment in Wales pushed against prevailing conventions in the sense that it was a necessary riposte to a London-centric status quo; a perceived tight-knit cadre, based around the then BBC Third Programme and top colleges and universities, which held the keys to the professional musical castle, and to which all kinds of composers not conforming to a certain background and outlook struggled to gain access. At any rate, the notion of what is ‘establishment’ and what lies outside or counter to it remains in some ways subject to cultural perspective – and indeed, on a wider, societal level, the whole question is emerging as a key point of tension in a world increasingly fraught with divisions along lines of identity and tribal self-interest.

But back to the BBC NOW, if you pardon the pun. Welsh Foundations 3 proved another fascinating insight* into Wales’s strong orchestral heritage as laid down by two perhaps quieter but nonetheless passionate individualists, Mathias and Alun Hoddinott (1929-2008); themselves building on the work of symphonist extraordinaire Daniel Jones (1912-1993). In a robustly performed concert, conducted by Rumon Gamba, it was in fact a symphony by Hoddinott – his impressively assured No. 2 of ten, written in 1962 – which came under the spotlight, together with Jones’s all-too rare Violin Concerto of 1966. Both works were dispatched with the kind of aplomb appropriate to their lack of compositional small talk; the Hoddinott full of intensely worked, brooding details amidst contrastingly big-boned, dramatic gestures, whilst the Jones proved the highlight of the afternoon in soloist Jack Liebeck’s wonderfully clear and idiomatic reading. Here it was the middle Lento that most compelled in its deft balance of rigour and expressivity; lush, full orchestral writing to lyrically angular solo cadenza.

Alongside these works, Mathias’s once-popular Laudi served as a generous reminder of the North-Walian’s rejection of what Gwyn L Williams eloquently described as the ‘greyness’ of Welsh religious non-conformity for a broader, more expansive sense of the spiritual. Meanwhile Anglesey-based Glyn, a composer who continues to embrace with vigour the solidity of tonally-based forms, here delved into medieval poetry with a blockbuster orchestral suite on Aneirin’s bardic tale of 6th-century battle, Gododdin.

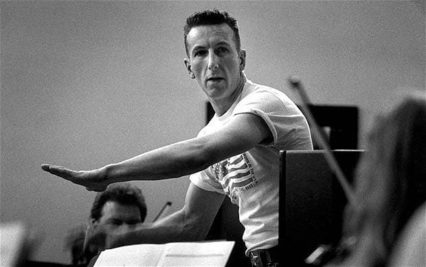

To my mind, in a time of increasingly dark nationalism, the title ‘Great Brits’ contains awkward echoes of 90s ‘Cool Britannia’ at the very least. But presumably – and for those less cynical than I – it was intended as a nod to the peculiarly British phenomenon of affection towards maverick outsiders. The sorely-missed Steve Martland was refreshingly unafraid to voice strong opinions, once letting off steam at what he saw as ‘this class thing’ in contemporary music: ‘I hate petty pretensions, stupid rules, everything that’s expected of you. I am arrogant, but it’s about the establishment, about what people will do for just one little performance at the Proms.’

Martland was a deeply engaged socialist, and I can only imagine him turning in his too-early grave at current, dreadful political developments in the UK and especially across the pond. His piece for string orchestra, Crossing the Border – written in 1990-91 and itself very much of that decade in its Andriessen-inspired, driving minimalism – seems more than ironically titled in the present context. Once memorably described as ‘psycho-pastoral’ by the Morning Star, under conductor Edwin Outwater the piece took the BBC NOW players considerably out of their comfort zone – but not positively so, as they struggled with its alternating stabbing counterpoint, hocketing motifs and surprisingly sensuous sustained lines.

The full orchestra fared far better with Graham Fitkin’s elastic-feeling and more sympathetic, yet equally rigorous Intimate Curve. Composed in 2014-15, the piece is a kind of slow-build funky concerto for orchestra, which Fitkin (b. 1963) describes as ‘probing the idea of sensory change over time and in particular the nature of arousal.’ He too studied with Andriessen, but his music is less coiled aggression than unalloyed joy, here delighting in crunchy James Bond brass and melody-driven juxtaposed blocks of sound. Fitkin recently commented on how others see his music, ‘I have been called “postmodern” but I have also been called “establishment”.’ Actually, I suspect they’re no longer mutually exclusive terms. But the idea is also interesting vis-à-vis Great Brits and changing fashions: perhaps, even by virtue of being recognised as at least one-time outsiders, these composers have already become absorbed into the mainstream. Not that that makes their music less interesting or worthwhile.

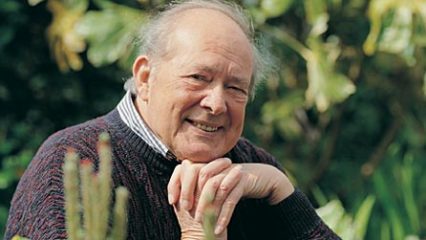

David Bedford in 2009, photo AlamyIndeed, the most fascinating, beautifully rendered piece of the evening turned out to have very dated elements, combining orchestra with a solo trio of prog rock-inspired electric guitar, bass guitar and drum kit (here I have to confess that it was an old chum of mine from my days playing with Icebreaker, Pete Wilson, who nailed the tricky bass part, alongside the excellent guitarist Mats Bergström and BBC National Orchestra of Wales drummer/percussionist Steve Barnard). David Bedford would have turned 80 this year and, coming back to unlikely coincidences, his astrophysics-inspired Star’s End was composed in 1974; just a year after Mathias’s Laudi, a stylistic universe away – but around the time Pink Floyd released Dark Side of the Moon and Tangerine Dream made John Peel’s 1973 album of the year with Atem. Conceived as a studio album, the work has sounds and ideas in common with these and other bands – as well as the Tubular Bells album by Bedford’s original guitarist, Mike Oldfield, and an affinity with certain strands of post-Cage experimentalism.

This was the first time Star’s End had been performed live since 1974. If its bluesier psychedelic aspects felt less convincing in today’s more self-consciously hipster world, the orchestral writing felt remarkably fresh and contemporary. With swirling yet static textures built from long, simultaneously rising and falling figures, the music edged in and out of diatonicism and shimmering chord clusters which coalesced at times into chorale-like passages. Concerned with entropy, or the ‘Heat-Death’ of the universe, this was genuine outsider stuff; teleported from 40-odd years ago via a wormhole Bedford made a very happy way to travel.

Welsh Foundations 3 – National Orchestra of Wales

BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, 27 January 2017

Conductor – Rumon Gamba

Jack Liebeck – violin

Music by William Mathias / Daniel Jones / Gareth Glyn / Alun Hoddinott

Great Brits 2 – National Orchestra of Wales

BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, 3 February 2017

Conductor – Edwin Outwater

Mats Bergström – electric guitar / Pete Wilson – bass guitar / Steve Barnard – drums

Music by Steve Martland / Graham Fitkin / David Bedford

* See here for reviews of Welsh Foundations 1 and Welsh Foundations 2

Graham Fitkin’s Concerto for multiple amplified recorders and orchestra, performed by BBC NOW and soloist Sophie Westbrooke, will receive it’s world premiere at the Vale of Glamorgan Festival on Friday 26 May, BBC Hoddinott Hall, 7.30pm

Both concerts were recorded live by BBC Radio 3, Great Brits for future broadcast. For information visit bbc.co.uk/now