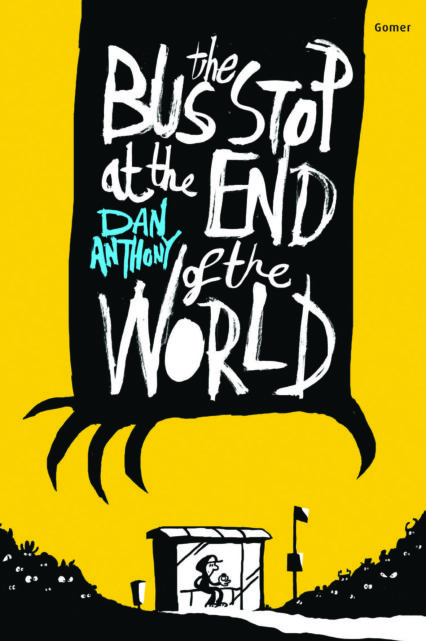

Dimitra Fimi talks to fantasy writer Dan Anthony about his new book The Bus Stop at the End of the World.

I read Dan Anthony’s new book, The Bus Stop at the End of the World (Gomer Press, 2017), nearly in one go. It is written beautifully, managing to combine believable, magical and funny characters, and blending the everyday with the fantastic seamlessly.

Richie lives in a farm cottage in west Wales with his army veteran dad and he is worried he is a “dead loss”: he can’t read properly, he is bullied at school, and he feels more at home in the bus stop that connects his rural existence with the town and school. Both the bus stop and Richie are liminal. Richie is an outsider (he has recently moved to that part of the world), he is at the threshold of adolescence (he’s 11), and he seems to understand animals and creatures from myth and legend who flock to the bus stop. The bus stop itself is an intersection: on the ground, buses drive past it criss-crossing the country; high above, aeroplanes use the area as a crossroads from and to the other side of the Atlantic; and underground, cosmic leylines join the place with mystical locations, such as Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Egypt. The bus stop is, therefore, a crossing, a typical place where the supernatural occurs and where everything is possible.

Richie lives in a farm cottage in west Wales with his army veteran dad and he is worried he is a “dead loss”: he can’t read properly, he is bullied at school, and he feels more at home in the bus stop that connects his rural existence with the town and school. Both the bus stop and Richie are liminal. Richie is an outsider (he has recently moved to that part of the world), he is at the threshold of adolescence (he’s 11), and he seems to understand animals and creatures from myth and legend who flock to the bus stop. The bus stop itself is an intersection: on the ground, buses drive past it criss-crossing the country; high above, aeroplanes use the area as a crossroads from and to the other side of the Atlantic; and underground, cosmic leylines join the place with mystical locations, such as Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Egypt. The bus stop is, therefore, a crossing, a typical place where the supernatural occurs and where everything is possible.

But will Richie be able to harness the power of the bus stop and the hidden power within him to save the world from the King? Can he become the “one-off” who will determine the fate of supernatural powers that still linger in the Welsh landscape? And, ultimately, can he save the world, his dad, and himself?

I’ll let you get to the ending of this wonderful book for yourselves, and discover trolls, witches, dragons and a flaming tree (all imagery that could have come straight out of the Mabinogion), as well as cowboys, bus timetables, and Elvis Presley! But I thought I’d share the answers to some of the questions I asked Dan when I met him to talk about the book. Enjoy!

DF: There is a long tradition of children’s books drawing inspiration from Welsh myth and folklore, such as the Mabinogion, or more recent folktales and beliefs. For example, my recent study, Celtic Myth in Contemporary Children’s Fantasy, examines Alan Garner’s The Owl Service and Jenny Nimmo’s The Snow Spider Trilogy, to name but a few. Do you see yourself writing within that tradition in this book?

DA: I can certainly say that, when I was thinking about writing The Bus Stop at the End of the World I was aware of Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, because, the strange tale spooked me as a child. A more powerful influence were however, the stories from the Mabinogion. But not at all in a literal sense. Quite the opposite. It always seems to me that the way the stories are told, rather than what actually happens, is the most extraordinary thing about them. There’s a sense that they are fragments of tales that have been knitted back together to make something that looks presentable – to a world that likes their stories packaged in certain ways, for economic and cultural reasons. To me the magic of the Mabinogion is almost in the stories that weren’t recorded, that blew away in the moment of telling, that flew off with the woodsmoke before they could be written down and organised to suit some sort of publisher. This idea, rather anarchic, unpackaged, distinct, unruly and hugely imaginative – in which the physical world and the metaphysical shape shift as if there is no difference between the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’ is what I was after. I got the idea because I came across a bus stop on Strumble Head in Pembrokeshire. As I wondered who on earth caught buses from this stop I noticed a sheep watching me. I guessed children would catch the bus to get to school. Then I considered the sheep.

What if, I wondered, the sheep could tell me the answer? Soon as I began talking to the sheep I knew I wasn’t exactly trying to reconstitute the Mabinogion. Thanks to the geography – I was in it… again.

DF: How specifically do you expect your readers to make links between the creatures Richie encounters and those from Welsh tradition? There is a red dragon there, for one, but we never quite get a clear sense of who the Wooly Woman is (a goddess, but which one?), for example, or whether Woody the troll, or the Scaries (the fairies), are strictly creatures of Welsh folklore or more universal legendary characters. Are these identifications meant to be specific or more fuzzy? (And does it matter?)

DA: Again, there is a connection, but it’s not direct, and I’m really not at all concerned if readers enjoy the story, but don’t make the connection. I’m really just trying to draw on the imagination within Welsh, and possibly other folk stories. I’m also trying to tell a story about a modern kid, with modern problems. It seems to me this contemporary feel is often absent from many of our reconstructions of folk tales. I didn’t want this story to be a about a fantastic place – a long, long time ago – I wanted it to be about today, now, after a warrior comes back from a war. It’s just that the war was the recent Afghan conflict – not, for example, the Trojan one.

The Woolly Woman? If she has a connection to Welsh folklore, to Welsh culture, it is that she is a powerful, and – to men – mysterious, woman. Richie and his Dad are, for whatever reason, fish out of water; when the story begins they are two blokes in a parlous state. So are the comic duo Kid Welly and Doc Penfro.

DF: The quest for the Blue Stone references the stones at Stonehenge having originated in Wales (and there is, of course, the famous story of Merlin moving the stones in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae). Were you aware of recent excavations at Stonehenge and the argument for the (possible belief in the) healing power of the “blue” stones?

DA: Absolutely. Again, I wanted to try and de-mystify, or perhaps, re-mystify the story. If the stones really were so powerful, you can imagine the kind of attention they would draw. I wanted to make the suggestion that people of the Stone Age weren’t much different to people today. A few locals decided to hide one of these apparently magic, healing, stones. In this story there is magic in the stone, but only Ritchie can imagine it back into existence.

DF: Who are the Spannermen? Are they the remnants of Wales’s industrial past who have taken a life of their own and have entered the world of folklore? (I am over interpreting here?) And was it a conscious decision to have a sheep as a character in a book set in rural Wales? (Shemi doesn’t utter a word, but she *knows* everything! And she’s relatable and memorable!)

DA: In a sense the kind of ‘creatures’ who appear don’t need to make much literal sense. Remember this story is a kind of stab at a certain kind of storytelling. And, as in all children’s stories, they have to work in the way that children’s imaginations do – children’s imaginations are far more powerful than adults’. I don’t think the original tellers of Mabinogion tales worried too much about logic, they were after powerful images. A woman constructed out of flowers seems to me to be a kind of robot. Creatures made out of junk metal, old washing machines, speaker cabinets, spanners and saws, are made in exactly the same way as Blodeuwedd.

Regarding Shemi – yes you are right – Shemi is a key character. Shemi sees the whole story – he gets it, he’s the only one who does, he’s seen it all before. Remember, Shemi the sheep gave me the idea. There was a story teller, a tramp-like figure who lived on the outskirts of Fishguard some time ago. Apparently he was a brilliant teller of tales – his name was James Wade, or Shemi Wad. So I’m told, Shemi Wad used to sleep in people’s hedges and gardens around the Goodwick and Strumble Head area.

After he died, I thought, if he was going to come back, he’d be sheep – standing by a gate, making notes.

DF: Would you say that this is a book about Richie finding himself and growing during the course of the book? Or is it a book about modern Wales’s firm links with its legendary past? Or are the two completely intertwined – the liminality of Richie matched by the liminality of the otherworldly characters in a location that is equally “betwixt and between”?

DA: The story is about Ritchie and how he overcomes some difficult problems. How, in doing so, he unblocks a lot of other difficulties, for his father, and even others around him. Of course, the story might not be true, it might be just what kind of happened in Ritchie’s head every time he went down to the empty bus stop. It might be the story he muttered to Shemi as he played with pebbles on the gravel. It might not really exist, in the way that most of us like things to exist. That, liminality, as you put it, that moment of expansion, like a Big Bang of the mind, is the folkloric idea I’m after. Symbols like the watching crow, the stone itself, which expands and (for me) connects the tale to the moon, which Ritchie describes as being ‘in his mouth’ at the beginning, and the inclusion of the car (which has driven far enough to reach the moon), busses, aeroplanes, landmine, operating theatres and Elvis Presley emphasises the immediacy, the ‘modernity’, and the accessibility of our quite wild story telling traditions.