Adam Somerset reviews Bettina Harden’s The Most Glorious Prospect, which covers sixteen gardens of Wales with illustrations, notes and bibliographies.

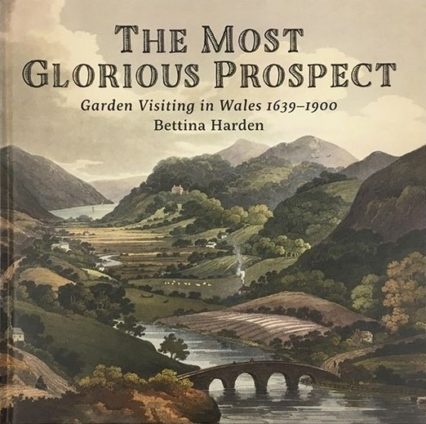

The Most Glorious Prospect is a book written from authority and experience. Bettina Harden is herself owner of an historic garden of Wales, outside Pwllheli, and was for six years Chair of the Welsh Historic Gardens Trust. She founded the Gateway Gardens Trust, the first charity with a mission to extending access to heritage through social inclusion. Her book carries the Graffeg imprint. The physical quality of books from publishers of Wales varies highly. Among them Graffeg is an unfailing guarantor of quality. It comes with 209 illustrations and 25 pages of notes, bibliography and index. It is by any standard a book of distinction.

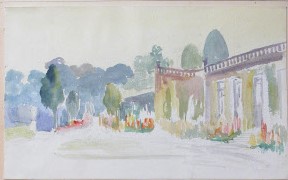

Its subject is sixteen gardens of Wales. North to south it covers Baron Hill, close to Beaumaris, to Piercefield in the Wye valley. Those in the north include Plas Newydd, Tan-y-Bwlch, Penrhyn. Those south of the Severn are well-known names: Hafod, Picton, Dynevor, Stackpole, Margam. Among the illustrations there are some highlights. Alice Douglas-Pennant painted Powys Castle garden in beguiling watercolour in 1892. A print of Devil’s Bridge from the nineteenth century gives the location a harmony and elegance lacking in 2018. An unknown artist of 1667 renders Llanerch from an aerial view. In a piece of eye-bending perspective the round pond is rendered vertically to show off the statue of Neptune.

The book’s subtitle is “Garden Visiting in Wales 1639-1900.” It is a record of how the locations were experienced by the many visitors who came to them. Some visitors were complimentary. Lord Lyttelton wrote of Plas Newydd: “the view from it is charming…the sweet country through which we had travelled…which ennobles prospect…the Menai winds, in a most beautiful manner.” He was at Wynnstay when only one wing had been completed. Nonetheless he thought: “the view from it is the most cheerful I ever beheld”.

Gardens were conceived to be works of art and some critics discerned aesthetic shortcomings. Sir Richard Colt Hoare was at Chirk in 1798 and recorded “a piece of water, badly planned and managed, made on a hill, contrary to nature…Thus two errors are created: Nature outraged, and a defect instead of a beauty.” Benjamin Heath Malkin at Stackpole took a similar view: “it may be questioned whether…a correct taste would have indulged itself in any such attempts.” The Honourable John Byng found Margam in August 1787 to be “in much disorder”. As for the woods “they appear to be very ill managed.” Reverend John Evans also disliked what he saw of Margam: “it is always disgusting to the eye of taste, to observe ancient and modern architecture blended together in the same edifice”. The park of Dynevor has always impressed but Dr George Lipscombe in 1799 critiqued the mansion as “a structure devoid of taste or elegance, and a great disgrace to the scenery which surrounds it”.

Bettina Harden’s chapters on the sixteen estates are framed by a scene-setting opening and a gazetteer on her subjects’ current fate and condition. She opens with a description of transport in Wales. Conditions were bad to the extent that “A Welsh Journey” became a phrase in its own right. In the books of the early eighteenth century roads were marked as “mere rights of passage.” Coach travel was significantly slower and more hazardous than horseback. When Jonathan Swift travelled to Ireland in the summer of 1713 Chester to Holyhead took him three days. Pictures illustrate the cliff path at Penmaenmawr both before and after its safety wall.

The rise in visitors was motivated by both politics and science. Thomas Johnson, who recorded the first ascent of Snowdon in 1639, and John Ray, an early traveller, were interested in plants and botany. The Act of Union of 1801 prompted the creation of Telford’s road to Holyhead and the bridging of the Menai Straits. Revolution and war in France staunched the opportunities for travel in Europe and interest from English travellers turned westward. By 1813 George Nicholson was applauding “the macadamising principle”. The new routes “have almost annihilated time and space, and London can be reached from Aberystwyth in twenty-four hours.”

The Most Glorious Prospect ends with summaries of the present day. The conditions cover a huge spectrum. Many of the properties suffered family bankruptcies. Baron Hill is derelict and roofless. The Home Guard tossed grenades into Penrhyn’s bath house. The collapse of the slate industry was ruinous for the owning dynasties. The Forestry Commission dynamited the wreck of Hafod in 1958. Piercefield Park is the site of Chepstow racecourse. Wynnstay is visible in fragments. Llanerch is privately owned. The author comments: “so I have not been able to see it in its present incarnation.”

But much glory has survived from Plas Newydd- both Anglesey and Llangollen- to Bodnant, Chirk, Picton, Stackpole. As for the once owners they were equal in ambition if less equal in likeability. But it is hard not to warm to Sir Thomas Myddelton who set to his walled garden in 1651 and celebrated his undertaking in verse. His first lines run:

When first I did begin, to make

This garden, I did undertake

A worke, I knew not when begun

What it would cost, ere it was donn.

The Most Glorious Prospect by Bettina Harden is available now from Graffeg Publishing.

Adam Somerset is an essayist and a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.