The novel Seaglass by Eloise Williams follows a thirteen-year-old Lark and her sister Snow embrace the distinctive nature of West Wales.

Not all the powers of the sea can make plastic safe or pretty, but who has not bent down to pick up and admire a piece of seaglass, its sharp shattered edges rounded by the tide to lustrous translucent pebbles of brown or green? They are just as much a product of the Anthropocene as the photo-oxidated coke bottles cluttering the tideline, yet seaglass has the charm of a functional object made functionless and beautiful by the smoothing ocean. The richness and strangeness of this particular sea-change are one of the running themes of Eloise Williams’ Spyglass, inspiring some of its best prose.

“Just think,” Mam says, looking at a particularly the beautiful piece of glass with a rose tint. “All those lives. All those people who threw things away.”

I never really thought of them like that before: each piece having a life, or two or three, attached to it. Mam is special like that.

“Perhaps this piece,” she holds aloft a piece of blue-white glass, “was part of a bottle that held a message for a lost love.”

The book begins with thirteen-year-old Lark and her sister Snow arriving at a caravan park on the shores of West Wales, aiming to give her sickly mother a break from the strains of the city. Exploring the woodland that borders the beach, Snow and Lark discover the remains of a bombed-out cottage, haunted by a ghostly girl in a green dress. As the spectre begins to exert an uncanny power over her mute, traumatised younger sister, Lark resolve to unravel the ghost’s mysteries before she can lead Snow into mortal peril.

The book is written in Lark’s voice, which is modern yet distinctive; her habit of counting down from ten before she blows up with rage is a great tension-building device, and there are some lovely passages where her interest in birds feeds into her descriptions, such as when she describes her mam-gu’s head snapping up ‘like a kingfisher with a catch’. Thematically, too, the book is pleasingly solid. Lark and Snow’s mixed-race parentage is introduced so casually that at first, it seems throwaway, but prejudice builds into one of the book’s central themes, with the cruel and childish bullying Lark and Snow experience paralleled by the hounding of the ghost, who turns out to have been a German refugee caught in a World War Two bombing raid. The West of Wales is vividly realised, both in the natural description of the beach and the onset of a sea fret, and in the characterisation of a social setting still very much influenced by the hippy migrations of the seventies. Refreshingly, this means that once the evidence for the ghost builds, there’s no staunch rationalist to declare that ghosts don’t, can’t, could never exist.

One of the challenges of writing fiction for children and young adults is to get the adults out of the way so that the adventure can begin. This was easier in the days when orphans were more common, and the author could wipe out both parents with a stroke of the pen, but there are plenty of reliable modern options. In Seaglass, we get parental illness: Lark believes her mother is dying and told her sister so, news which shocked Snow so badly that she doesn’t speak for most of the book. It’s a device that works to keep the parents distracted and self-focused, but it does mean that the book begins with Lark at the maximum emotional intensity and nowhere else to go. Even the presence of a ghost can’t wind her up much further, and it’s a relief when she gets back into the company of her friends and frenemies, and starts to loosen up a little. The mysterious illness later turns out to be a non-threatening case of depression, a twist that’s better than a miracle cure as a means of rounding out the book, but almost as unlikely. Even the most lackadaisical of parents could probably have figured out that something was wrong when their younger daughter falls mute and gotten to the bottom of the misunderstanding.

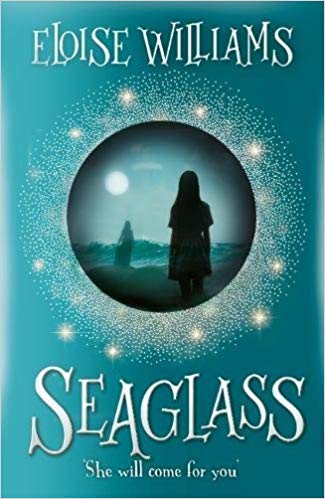

Overall, however, Seaglass is very successful as a young adult ghost story, vividly realised, pleasingly creepy but not gory or violent, with an engaging narrative voice and chapters that end on solid cliffhangers. Almost as handsome in its cover design as seaglass itself, it would make an excellent beach read.

Seaglass by Eloise Williams is available now from Firefly Press.