Wales Arts Review asked some the top writers of Wales to choose what they think are the best Welsh books of the decade. The list includes novels, short stories, poetry, history, memoir, diaries, criticism and social commentary, and shows an astoundingly rich ten years in Welsh writing.

Horatio Clare

My Welsh book of the decade has only recently been published. It is a glittering and ferocious portrait of our time, set in west Wales. The extraordinary situation in which we live, in one of the richest countries of the world, with an education system that fails the poorest, with a social system that divides the rich from the rest, and with a system of values that shames us all, built on getting and spending our way to the grave – a society, in short, which seems to lack vision, idealism, compassion and calling, is bitingly captured in this wonderfully angry, funny, involving novel, the story of three damaged characters who see a vision on a Welsh hillside. The book is Broken Ghost (Jonathan Cape, 2019) by Niall Griffiths, and it is a bitter and sparkling masterpiece.

Menna Elfyn

I did not expect to be so bowled over by Emyr Humphreys’ Shards of Light (UWP, 2019) as I considered him one of our great novelists, but this volume of poetry written in his hundredth year is full of luminous things. ‘Shards’ is the perfect word as it recognises the fragility of life, but oh, the light is what gives us the gleam as to the nature of being. There is profundity, there is lightness of touch, filling the void of today’s drivel and dross. Here is poetry of undiminished power, sparseness of language and clarity of voice and as always with a renewed sense of wonder even in the shadow of mortality. Poems which will live on and, for us, the lucky ones — to live by.

Richard Gwyn

Addlands (Granta, 2017) by Tom Bullough is a beautifully written novel, with astutely observed characters, and a profound appreciation of a landscape and its inhabitants, human and animal, their lives irremediably intermeshed; a place where loss and sorrow are quotidian facts, and the outside world – be it of machines, taxes, or advertisements – is held at bay. I felt, reading it, as though a kind of secret knowledge were being imparted, with Radnorshire as the kernel of the world, and at the middle of this known place, an otherness.

Addlands (Granta, 2017) by Tom Bullough is a beautifully written novel, with astutely observed characters, and a profound appreciation of a landscape and its inhabitants, human and animal, their lives irremediably intermeshed; a place where loss and sorrow are quotidian facts, and the outside world – be it of machines, taxes, or advertisements – is held at bay. I felt, reading it, as though a kind of secret knowledge were being imparted, with Radnorshire as the kernel of the world, and at the middle of this known place, an otherness.

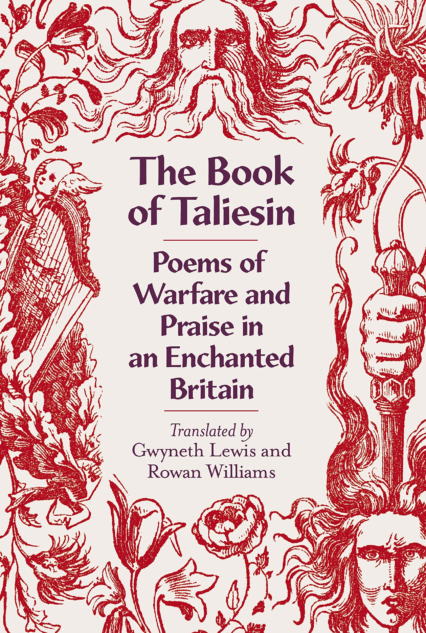

Catherine Fisher

As an Enchanted Britain is what we all need at the moment, I have chosen The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain (Penguin Classics, 2019), a marvellous translation, as my Book of the Decade. Rowan Williams and Gwyneth Lewis have produced a scintillating version of the strange and riddling works of the ancient masterpiece, and an introduction and full notes that incorporate all the latest scholarship fused with a real poetic insight. It’s a great contribution to the culture of Wales, a fascinating read, and surely will prove to be the seedbed of many novels and poems of the future.

Joe Dunthorne

A raw and unforgettable short novel from the Hemingway of Ceredigion. The Dig (Granta, 2014) by Cynan Jones tells the story of a lonely sheep farmer and a malevolent badger baiter. The latter is a man every bit as sinister and charismatic as The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. The Dig is a masterpiece of compression, packing huge amounts of emotion and tension into just 176 pages.

Darren Chetty

Martin Johnes’ superb book, Wales: England’s Colony? The Conquest, Assimilation and Re-creation of Wales (Parthian, 2018), is engaging, accessible and timely. Rather than opting for polemic, Johnes take us through a history of Wales, organised into three stages, that cannot be neatly reduced to a clear yes or no in answer the book’s central question. He demonstrates that contempt for the culture of the people of Wales went hand in hand with the economic exploitation – but that Wales was often a willing beneficiary of British colonialism. This is in part a book about history as a discipline – what it can and cannot achieve and how it is so often bent and shaped in service to contemporary political debates. Johnes concludes that whilst history has shaped Wales it is the people of Wales who will shape its future.

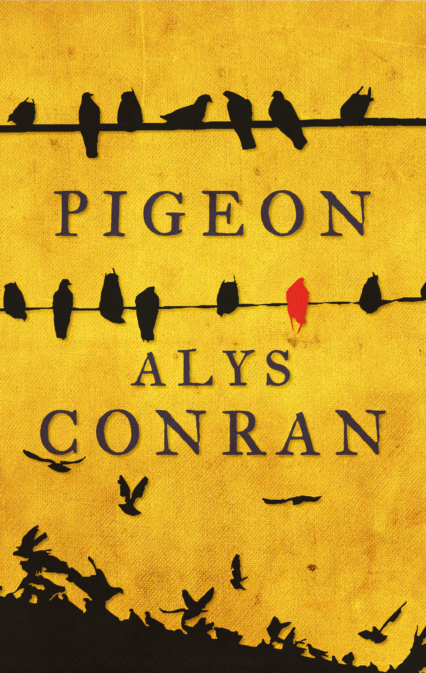

clare e. potter

Alys Conran’s debut novel Pigeon (Parthian, 2017) is hands down my favourite novel of the last ten years. Exceptional writing where language functions as character: Geiria, Words, Welsh and English, how they intersect, reveal something of culture and friendship. Pigeon went deep into my heart. I wanted to take him out of the shed, out of hurt and neglect. But this story had other plans for him, diolch byth, and he found his own way out. ‘With Pigeon everything is bright and big and better than you’d think it was’ (p.8). This novel teaches empathy, teaches us to love those we might judge.

Natalie Ann Holborow

As a student, I was blown away by the writing of Dylan Thomas Prize-winning writer Rachel Trezise. I remember devouring Sixteen Shades of Crazy (The Borough Press, 2010) in the space of a week; the sharp dialogue, razor-sharp character description, and the absolute credibility of the gritty Valleys setting punched me clean in the stomach. It spurred me to fall in love with writing fiction again after so long enamoured with poetry. She’s a bold, refreshing voice in Welsh writing, and I’ve often revisited the book as an example of how to write compelling and authentic dialogue. (If you haven’t guessed already, I’m still something of a fangirl.)

Niall Griffiths

From a cramped and crowded field – this has been a rich decade for writing about Wales – the work that springs out for me is the William Condry Reader (Gomer, 2015), edited by the great Jim Perrin and with a foreword by the great Gwyneth Lewis. Some of the most wondrous nature writing ever to come out of these islands. Crystalline prose, sense of wild awe, ego-free transmissions of calm and acceptance. Vital and beautiful.

Sophie McKeand

Pascale Petit’s dark collection, Mama Amazonica (Bloodaxe, 2017), reaches into my heart to squeeze and squeeze. These are epic, achingly beautiful poems of love, abuse and self-betrayal that are, ultimately, a celebration of the glorious tenacity of life in multitudinous shape-shifting form. That these multifaceted poems simultaneously expose, in microscopic detail, the horrors of the dysfunctional family, while unmasking our patriarchal culture’s violation of Mother Earth, is nothing short of genius, and is what lifts Mama Amazonica into a poetic stratosphere of its own.

David Llewellyn

The Richard Burton Diaries (Yale University Press, 2013) are an entertaining blend of showbiz gossip and soulful Welsh introspection, taking us from Burton’s Neath Valley childhood to his Hollywood fame and fortune. We get the highs (buying the world’s most expensive diamond – “I got the bloody thing for $1.1million”) and the lows (most of them booze-related), but Burton is charming company throughout. The longer entries are probably the closest we’ll ever have to his memoirs and reveal a keen literary mind, a legacy of the rich intellectual life of South Wales’ coal mining communities.

The Richard Burton Diaries (Yale University Press, 2013) are an entertaining blend of showbiz gossip and soulful Welsh introspection, taking us from Burton’s Neath Valley childhood to his Hollywood fame and fortune. We get the highs (buying the world’s most expensive diamond – “I got the bloody thing for $1.1million”) and the lows (most of them booze-related), but Burton is charming company throughout. The longer entries are probably the closest we’ll ever have to his memoirs and reveal a keen literary mind, a legacy of the rich intellectual life of South Wales’ coal mining communities.

Manon Steffan Ros

Light Switches Are My Kryptonite by Crystal Jeans (Honno, 2017) is a punchy, brave novel that feels absolutely Welsh whilst being urban, honest, and real. It was a deserved winner of the English language prize for fiction at the Wales Book fo the Year awards in 2018. It balances touching tenderness with some gut-punching moments of hurt and pain. Crystal Jeans’ writing stays with me always- she’s a genius.

Jonathan Edwards

Alan Perry’s Waters (Moonstone Press, 2017) is a collection of poems that for me does all that poetry should. Accessible and unpretentious, it goes for the right target – the human heart – and hits home again and again. Moving in its explorations of family history, sophisticated in its management of time, playful in its forms, it is a collection I keep going back to and it is, simply, a gift and a joy.

Ailbhe Darcy

I’m a newcomer to Wales, an interloper. It’s hubris for me to choose. But who could pass up the chance to praise Wales for being – in a kingdom disdainful of multilingualism – a gateway to the world? Nia Davies’ editorship of Poetry Wales, for half of the decade, was exemplary in this regard. The season I arrived, Poetry Wales featured six Galician poets I’d never encountered, as well as new work by Aase Berg, translated by Johannes Göransson – who’d been my teacher back in South Bend, Indiana. It let me know that I could make a home in this place. An editorship is not a book, but I choose it.

Adam Somerset

Russell Davies’ Sex, Sects and Society (UWP, 2018) is a rebuke to a telling of history as piety and Welsh exceptionalism. Illness and death, sin and suicide stalk its pages but so too do invention, laughter and sex in large amount and variation. The printing presses of the era were churning out pornography in abundance. A culture where an undertaker named Percy Edwards becomes “Perce the hearse” has to be one on its own. A review concluded: “If this social history is the stuff of nightmare for Tourist Board and Heritage Wales, it is genuinely revealing of a period filled with vivacity, volatility and variability”. As for the writing it was described as “comprising a density of detail and a gusto of style.”

Mab Jones

So many Welsh writers had a go at the John Tripp Spoken Poetry Award, but had never read any of Tripp’s work. It was, in the noughties, very hard to come by. The Meaning of Apricot Sponge: The Selected Writings of John Tripp (edited by Tony Curtis; Parthian, 2010) was a vital and timely publication. This mighty tome remedied that lack, bringing Tripp’s wit and lively character to life in a 180 page collection of poems, stories, essays, and more. I admire Tripp’s range of form, as well as his sparkling style. He was never dull, and his work brought Wales, in words, to life. Tripp was important, acknowledged, but until this anthology, a little bit overlooked.

So many Welsh writers had a go at the John Tripp Spoken Poetry Award, but had never read any of Tripp’s work. It was, in the noughties, very hard to come by. The Meaning of Apricot Sponge: The Selected Writings of John Tripp (edited by Tony Curtis; Parthian, 2010) was a vital and timely publication. This mighty tome remedied that lack, bringing Tripp’s wit and lively character to life in a 180 page collection of poems, stories, essays, and more. I admire Tripp’s range of form, as well as his sparkling style. He was never dull, and his work brought Wales, in words, to life. Tripp was important, acknowledged, but until this anthology, a little bit overlooked.

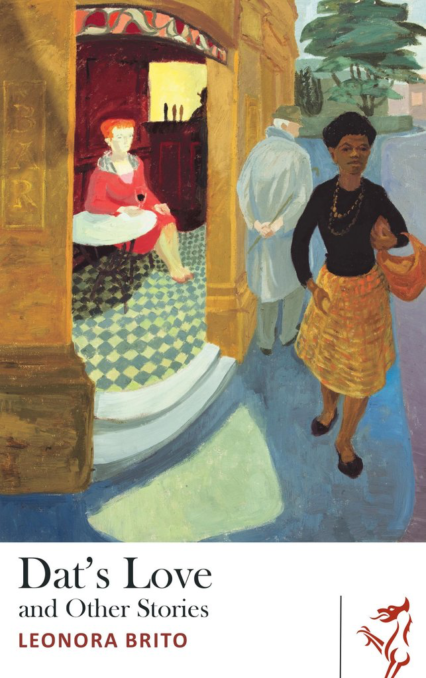

Nigel Jarrett

Wales is reluctant to discard fantasy images of itself long ridiculed beyond its borders. Part of a reality had long existed in the capital’s docks area, where Leonora Brito, of African Caribbean origin, began writing stories of acuity and vivid characterisation. Dat’s Love (Parthian, 2017) raised the possibility that a racially diverse Wales might emerge from the ghettoization, social and cultural, in which its promise was stifled. Dat’s Love, a collection first published by Seren in 1995, was re-published presciently by Parthian in 2017 as a Library of Wales classic. And deservedly so. Brito died in 2007, aged 52.

Kate North

My choice for the best Welsh book of the decade is The Last Hundred Days (Seren, 2011) by Patrick McGuinness. This novel is fascinating, exciting and terrifying. It traces a time of political and social change in Romania while offering us lessons from the past and questions for the present. It is a dramatic retelling of a significant period in Twentieth Century European history.

Zoë Brigley

Two of my favourite Welsh books from the last ten years both deal with violence in a thoughtful and perceptive way, and they top and tail the decade. What the Water Gave Me by Pascale Petit was published by Seren in 2010, and it is a series of poems inspired by the life and art of Frida Kahlo. It is hard to choose from among the many collections that Petit has published in the past decade, but these poems begin to show the healing power that exerts itself across her work. Take the moving lines in ‘Remembrance of an Open Wound,’ which speak both for Kahlo’s horrific traffic accident as a child and for all survivors: “I didn’t expect love to feel like this – / you holding me down with your knee / wrenching the steel rod from my charred body / quickly, kindly, setting me free.” The other book that I am keen to mention was just published this year (again by Seren) but this time it is a novel: Robert Minhinnick’s Nia. The story is a deliberate, thoughtful portrait of what it is like to live with trauma, and it is incredibly empathetic with the situation of women living with the threat and memory of violence. It’s a great portrait of Porthcawl’s peculiarities, and also speaks to the eerie magic of nature as a space with the potential for healing, but ultimately with its own will, and desires. For me both writers are incredibly powerful because they interrogate our relationships with nature and each other.

Aled Smith

One of my favourite books from the last decade would have to be the collection of short stories by Thomas Morris, We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber, 2015). Ten bitter-sweet tales that provide a glimpse into the day by day lives of ordinary people living in South Wales. There is an honest power in Morris’ straight and uncluttered prose which manages to reveal the particular truths known and the common universal sadness felt by his small-town characters. The minor descriptive detail spread across each page is precise and impressive, and the penetrating humour doesn’t deflate from its overall tone of quiet tragedy.

Hayley Long

From the intriguing opening sentence right through to the deliberately understated ending, every word of Gary Raymond’s short novel The Golden Orphans (Parthian, 2017) adds up to a beautifully crafted thriller. By means of an unnamed narrator, Raymond pulls us into a Cypriot landscape which is clearly marked with the scars of the 1974 division, and yet somehow simultaneously evokes an earlier era when the most compelling paperbacks all had orange and white stripy covers and the crime thriller was king. A wonderful read.

Joao Morais

I would be lying to myself if I didn’t admit that my favourite book of the last decade by a Welsh author was Vegan 100 (Quadrille, 2018) by Gaz Oakley. Not a week has gone by where I haven’t looked at this book for inspiration, and not a month has escaped, when I’ve been in the country with my own kitchen at hand, without me following one of his often creative and intricate recipes verbatim. I’ve learnt a lot from it, and will continue to do so for the rest of my life. Sorry for the pretentious answer, but it’s the truth.

Jo Lloyd

Among so many good Welsh story collections this decade, two favourites: Carys Davies’s The Redemption of Galen Pike (Salt, 2014) for intense focus and beautiful precise prose, whether in South Australia or Southerndown, and her subtle contemporary version of the twist, which reveals itself as corkscrewing through the story from the start. And Thomas Morris’s extraordinary debut, We Don’t Know What We’re Doing (Faber, 2015), for clear-eyed generosity, introducing Caerphilly Castle as its own black monolith, around which turns all of human life and even afterlife.

Siôn Tomos Owen

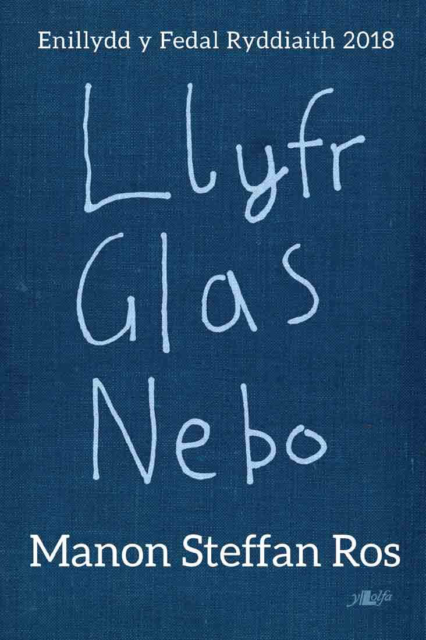

The 2018 Eisteddfod Prose Medal winning and Book of the year 2019, Llyfr Glas Nebo (Y Lolfa, 2018) by Manon Steffan Ros is a phenomenon. A short dystopian novel about a single mother and her young family trying to survive a nuclear fall out with alternating narrative between mother and son in the blue notebook of the title. Written for young people, it sold out within a week and is already on its 4th reprint, been introduced as a GCSE text and turned into a play. The simple language exploring loss of nature, of human contact and of language deserves to be read in any language.

The 2018 Eisteddfod Prose Medal winning and Book of the year 2019, Llyfr Glas Nebo (Y Lolfa, 2018) by Manon Steffan Ros is a phenomenon. A short dystopian novel about a single mother and her young family trying to survive a nuclear fall out with alternating narrative between mother and son in the blue notebook of the title. Written for young people, it sold out within a week and is already on its 4th reprint, been introduced as a GCSE text and turned into a play. The simple language exploring loss of nature, of human contact and of language deserves to be read in any language.

Helen Pendry

It’s not a book, it’s a gateway to books. Publications like O’r Pedwar Gwynt and Wales Arts Review enable two of the greatest pleasures in life: making unexpected connections and seeing things from a new angle. My literary ‘discovery’ of the decade has been the American writer Marilynne Robinson, whose novels and essays struck me as very ‘Welsh’. M Wynn Thomas’s piece ‘Chwilio am yr enaid’ (OPG 9) deepened my understanding of the connection between Robinson’s work and a certain Welsh sensibility, and introduced me to Emyr Humphreys’ great novel Outside the House of Baal (reissued by Seren in 2019).

Cynan Jones

Picking one book from the last ten years is a very difficult thing. Just one from the many books out of Wales that have struck me this last decade. But! That’s the game. In the end, I’ve gone with a story whose prose gripped me the tightest, and imagery that hasn’t let me go. Carys Davies’ West (Granta, 2018).

Eloise Williams

My choice for Welsh book of the decade is Hayley Long’s The Nearest Faraway Place (Hot Key Books, 2017). I loved this book and felt thoroughly bereft when I’d finished it. It’s a poignant, beautiful story which examines the love between siblings and the impact of loss. Moving through grief with empathy, humour and honesty, the author takes the reader on a fully encompassing emotional journey. Populated by brilliantly realised characters, peppered with references to Dylan Thomas and music, it brings the contrasting landscapes of New York and Aberystwyth to life vividly. This story broke my heart and then fixed it.

Richard Owain Roberts

An international best seller, translated into numerous languages worldwide and with a Hollywood adaptation in development, Amy Lloyd’s debut thriller The Innocent Wife (2017, Penguin), is my Welsh book of the decade. Lloyd, in her debut novel and again with 2019’s One More Lie, announced and then confirmed herself as a global force in literature for the decades to come, an author with an innate mastery of genre, aesthetic, and a uniquely identifiable prose style. For sure the most important Welsh writer right now.

Molly Holborn

A book that really stood out to me the moment I read the first ten pages was Bad Ideas/Chemicals (Parthian, 2017) by Lloyd Markham. It’s fantastically surreal and has the makings of a cult classic. For me, this book was a sign of the times for a lot of young people facing the dilemmas of the world. The characters are all beautifully unique and developed and the story is powerful and strange. I read it all in one day and loved every page.

Glyn Edwards

How to follow up on what must be Wales’ best-selling, best-reviewed poetry collections since the millennium? Having attained that great rarity in literature – commercial and critical success – with his debut collection My Family and other Superheroes, Jonathan Edwards’ Gen (Seren, 2019) has attained perhaps even more accolades. Again, there are poems that fixate the experiences of a teenager and their pivotal moments between innocence and adulthood. There are poems about Aberfan and Capel Celyn, about scares in Welsh history and scars in identity. There are poems warmed by the Edwards’ sincere charm and humour, and there are those where the intrusive narrative voice is distinctly different from the poet’s, where the reader is compellingly coerced and complicit in the observation of a private moment. Whether it is the ‘love’ for 100m sprinter Ben Johnson we race alongside ‘for a day’ in 1988, the love we mourn for ‘in the kettle, in the fridge, in the ceiling above’ a bed, or the love that longs for an ideal to ‘make this where you are’, all the poems in Gen are charged by the heart.