Anna Lewis reviews the latest collection, The Black Place, from Tamar Yoseloff.

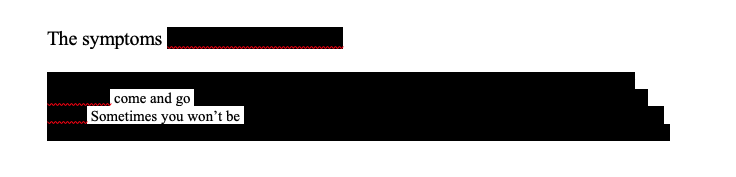

Tamar Yoseloff’s new collection The Black Place contains amongst its pages three immediately visual works. ‘Redaction 1’, ‘Redaction 2’ and ‘Redaction 3’ are each formed from rows of black blocks, in between which certain words are allowed to break through. Here is the beginning of ‘Redaction 1’:

As it proceeds, despite the very few and fragmentary words used, the poem becomes chilling. The black blocks, initially sinister in their apparent occlusion, begin to seem protective, holding in check a reality which bursts through in occasional instances of dreadful comprehension:

The text behind the black blocks, we learn from the notes, Yoseloff took from a pamphlet called Understanding Kidney Cancer, published by Kidney Cancer UK. This collection was written in the aftermath of the poet’s diagnosis, and the tone of the poems is raw, swinging from anger and resentment to disappointment and despair. There is little in the way of resolution or redemption, but equally there is little in the way of outright fear, its existence only hinted at, as through the gaps of the ‘Redaction’ poems. That triptych shows us in neatly subversive fashion how the ‘black place’, or inner darkness, can in fact hold the clarity of truth, and how hard we sometimes work to conceal it.

In ‘Cuts’, a long poem described in the blurb as the book’s ‘central sequence’, Yoseloff explores this tension between what is concealed or private, and what is made visible. Following a conversation with a consultant, in which her condition is revealed:

On the street the air is strange;

my secret’s blown. Fag ends stub

the pavement, the Standard blasts

Inferno – a tower fixed in flames.

There has to be someone to blame.

The poem makes further references to the Grenfell disaster, drawing parallels between the tower’s notorious ‘cladding’ and the materials of the Yoseloff’s own body:

… piss and blood for plastic cups.

I want to be all surface, nothing deep.

As her body gives up its secrets, the poet watches

… consultants handle me, a piece

of meat, a neat package of guts.

I practise leaving my body:

it’s not happening to me,

it’s happening to someone else,

someone who’s gone viral…

Serious illness brings with it sudden exposure: the body becomes a problem to be solved by experts, its substances clues to be examined, its outcome a point to be proved. ‘Cuts’ demonstrates the pain of this traumatic loss of privacy, but it is not quite the same thing as the exposure occasioned when a person’s death becomes a news story to be argued over by politicians, turned into metaphor by poets, and casually referenced in poetry reviews. The poet’s illness is only truly public property as a result of the poems she herself has written and published: whatever is happening to her body, she remains in control of her own narrative.

These are, for the most part, closely controlled poems: Yoseloff’s language is tense and spare, almost as though speaking is an effort:

… It’s already morning in Australia.

How exhausting. Someone is always

crowing about clear blue sky.

(‘Night Mode’)

The emotional experiences behind the poems are at their most conspicuously restrained in the ‘Redactions’ pieces, but a similar repression acts throughout the book. Prosaic, hard, built of short phrases, these poems have the textures of the city; but while those set in urban landscapes can be bleak (‘The city stirs, planes drown out birds, / the fox cries like a strangled child…’ – ‘Dawn’), there is no solace to be found in the countryside. Watching two rams fighting from a train window in ‘Sheeple’, the speaker wonders: ‘What ticks in their spongy brains? / The rest chew cud, footrot rooting them…’ In ‘Holiday Cottage’, the speaker has attempted to escape to a rural idyll, but ends up ‘… stuck to the window in wait / for sun.’ There is, perhaps, an unease with the wildness of the rural landscape: the unpredictability of its creatures, its vulnerability to natural forces.

Later in ‘Holiday Cottage’, the narrator’s gaze moves inwards, to

… dream of England: the shire bells,

the box set, the M&S biscuit tin,

the empire we’ll never find again;

detained in this hole…

a leave to remain.

It is not quite clear to me how this poem justifies its ending, with its allusions to immigration processes and the detention of those unwelcomed by the state. The disappointment of those whose journey across the world in search of a better life has failed is surely on a different scale from the disappointment of a washed-out weekend break. Read in the context of the book as a whole, perhaps the folly of nostalgia for a fallen empire can be seen as a metaphor for the vain hope to regain an earlier time before the shock of illness; stuck at the window, unable to leave the house, the narrator is equally confined in this new era of her life, watching the weather close in. But perhaps this is stretching the interpretation a little.

There are a couple of poems in The Black Place where the tension relaxes, and a more lyrical mode emerges. ‘Little Black Dress’ recalls the narrator’s student days, carefree to the point of carelessness, when in charity shops ‘… we picked over Givenchy like vultures; / my wardrobe belonged to the dead…’ The quick, rhythmic pace of this poem and its self-deprecating humour give it a freshness that is not always present elsewhere in the collection. Another more lyrical, but gentler, piece is ‘Darklight 1.’, a tender and quietly musical reflection on human mortality and the eternity of the universe. The narrator recalls:

Once I saw the aurora from a dock in Norway.

Men were going about their business, hauling

great loads from one bay to another.

The aurora was nothing to them, it had lost

its wonder…

… I practise my ghost walk,

for when I need to haunt; I am all soft edges,

a silhouette caught on the horizon.

Here, the indifference of the world to human suffering can be understood not as cruelty or hardness, but the dispassion of a universe infinitely larger than any of us, yet of which we are all a part. There is a suggestion that we may, indeed, be something more than our mortal cladding. It is the closest The Black Place comes to peace.

You might also like…

Anna Lewis takes a look at A Bright Acoustic by Philip Gross. Examining the interplay of the material and the immaterial, Gross’s A Bright Acoustic is an image rich, lyrical collection of poetry.

Anna Lewis is a contributor to Wales Arts Review.