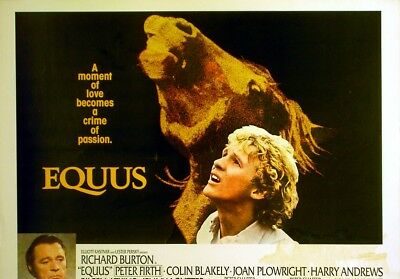

One of the less significant consequences of the lockdown of 2020 was that it cut short a season of Richard Burton films, introduced by academics, taking place at the independent Cinema and Co. in Swansea. The stimulus for arranging the series was the opening of a major exhibition on the actor Richard Burton — ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ / ‘Bywyd Richard Burton’ — the result of a collaboration between The National Museum in Cardiff and the Richard Burton Centre and Archive at Swansea University. The exhibition is about to re-open at the National Museum and, it is hoped, will run until October 2021. This is the first of a series of essays to run concurrently with the exhibition, curated by Daniel G. Williams, director of the Richard Burton Centre at Swansea University. Each essay will discuss a specific Burton film; here Daniel G.Williams kicks the series off with his exploration of Equus.

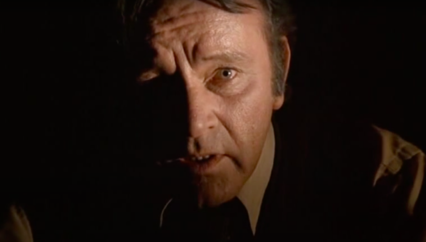

‘Can you think of anything worse one can do to anybody than take away their religion?’ That question, asked by Richard Burton playing the role of psychiatrist Martin Dysart, lies at the heart of the film Equus (1977). It is a question that the psychiatrist is asking of himself and may be applied more broadly to psychological demystifications of religious belief. It is a question that we might ask of our secular culture, especially in its exported, colonising, forms. And it is a question that might be asked in relation to Richard Burton, whose gradual alienation from the crucible of the Welsh language Nonconformist Protestantism in which he was formed is one of the implicit narratives informing the ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ exhibition soon to re-open at the National Museum in Cardiff.

The actor John Gielgud, commenting on Richard Burton’s arrival as a Shakespearean actor on the English stage, claimed that the Welshman ‘arrived from nowhere’. Even where Burton’s Welsh background is acknowledged — as in Melvyn Bragg’s biography Rich (1988) or in Tony Palmer’s fine documentary film In from the Cold (1988) — it is often just that: a background in which the young Burton dreams of playing outside half for Wales to a soundtrack of a male voice choirs. Part of the reason for this is that the trajectory of Burton’s life was outwards. Outwards, initially, from his earliest years in Welsh-speaking Pontrhydyfen to the more English-speaking society in Tai Bach. Outwards, later, from the world of Richard Jenkins, via the tutelage and guidance of Philip Burton, to the world stage and international reputation of ‘Richard Burton’.

If we read ‘religion’ in the opening question metonymically, as a part that stands for the multifaceted social network in which Richard Jenkins was nurtured, then the application of the question to Burton’s own life may lead us to ask: what is left behind in that process of moving out?; what are the costs of ‘Becoming Richard Burton’? In a fairly well-known interview from 1966, Kenneth Tynan asks Burton whether it was exposure to the rhetoric of the Welsh pulpit that led him to the stage. Burton answers:

Oh yes, unquestionably, and I think we have a word in Welsh called — misused I believe by you lot — called hwyl, and nobody can ever translate it, but it’s a king of longing for something, a kind of idiotic, marvelous, ridiculous, longing.

Hwyl means fervour, particularly the excited oratory of a preacher. It’s the word that makes sense in this context. But Burton describes hiraeth — the longing for something. It is an odd mistake to make. As Paul Ferris notes it’s ‘as though some different train of thought has broken into the sentence’. Hiraeth and hwyl are among the most hackneyed and repeated alleged characteristics of the Welsh, and Burton had probably used these words many times in conversations and interviews. But nevertheless, the idea that behind the hwyl of his stage persona there lies a hiraeth for a lost past and prior self is suggestive. This is perhaps particularly the case in relation to Englishman Peter Shaffer’s Equus, a play Burton selected as a vehicle for resurrecting his waning career in the mid-1970s. In his Living in the End Times (2010), the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek argues that

[a]lthough the best-known Dysart was Richard Burton, who played the role on Broadway and in the cinema, two other actors who have played the part evoke much more interesting associations: Anthony Hopkins and Anthony Perkins – Dysart: between Hannibal Lecter and Norman Bates!

I disagree, because Equus may be read in relation to Burton’s own life and this leads to a series of equally interesting associations.

Equus was originally a stage play, first performed in 1973. It tells the story of a psychiatrist who attempts to treat a young man who has a pathological religious fascination with horses. In the 1977 film version, Burton plays the role of psychiatrist Martin Dysart, who is asked to treat the seventeen-year-old Alan Strang. Alan has, inexplicably, blinded six horses in the stable where he works. Dysart discovers that Alan’s mother, a devout Catholic, read to him from the Bible, while his atheist father, concerned that Alan was taking an unhealthy interest in the more violent aspects of the Bible, destroyed the picture of the crucifixion that Alan had at the foot of his bed, replacing it with one of a horse. Alan develops his own horse-cult as a result. At the end of the film Dysart doubts that he can help Alan and explains his feelings to Hesther, the lawyer who initially asked him to look into the case. Dysart is making reference here to the sterility of his relationship with his wife, and to his interest in Greece and Greek mythology, which from Freud’s ‘Oedipus complex’ onwards plays a significant role in the formation of psychoanalysis:

Three weeks a year in the Peloponnese, every bed booked in advance, every meal paid for by vouchers, cautious jaunts in hired Fiats, suitcase crammed with Kao-Pectate! Such a fantastic surrender to the primitive. And I use the word endlessly: ‘primitive’. ‘Oh, the primitive world’, I say. ‘What instinctual truths were lost with it!’ And while I sit there, baiting the poor unimaginative woman with the word, that freaky boy tries to conjure the reality! I sit looking at pages of centaurs trampling the soil of Argos — and outside my window he is trying to become one, in a Hampshire field! […] I watch that woman knitting, night after night — a woman I haven’t kissed in six years — and he stands in the dark for an hour, sucking the sweat off his God’s hairy cheek! [Pause] Then in the morning, I put away my books on the cultural shelf, close up the kodachrome snaps of Mount Olympus, touch my reproduction statue of Dionysus for luck — and go off to hospital to treat him for insanity.

Dysart has come to see value in Alan’s intense sexual-religious life. It makes him realise how sterile his own life is. He finds in Alan the living embodiment of what he was looking for in ancient artifacts.

Dysart’s realisation leads him to question his own role in the treatment and attempted rehabilitation of Alan. The play may be read as a version of the ‘Pygmalion’ story. In George Bernard Shaw’s adaptation of Ovid, Professor or phonetics Henry Higgins has to make a ‘lady’ of cockney flower girl Liza Doolittle. Richard Jenkins was to undergo a similar process of developing his voice under the tutelage of his teacher at Port Talbot Secondary school, Philip Burton. (The ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ exhibition contains the programme for the school’s performance of Pygmalion in which Richard Jenkins plays Henry Higgins). In Act One of Equus, Dysart’s disturbing dream, in which he sees children being sacrificed in ancient Greece, comes to represent the idea that he and his profession are sacrificing children’s individuality in order to assimilate them into the social norms of the modern world. It is through therapy — rather than elocution lessons — that Dysart is urging Alan to leave behind his pagan, backward, beliefs in order to enter normal society. But, in the process, he begins to see the value of Alan’s belief system. Žižek offers an interesting reading of this. Equus, states Žižek,

is usually read in a New Age way, as a play celebrating the living force of a re-awakened pagan spirituality; however, the play’s narrative sustains the opposite message: pagan spirituality explodes when our Western (Christian) religion fails, when the symbolic Law it guarantees collapses. What appears more ‘primordial’ is thus a secondary reaction, a myth concocted to fill in the hole of the suspended paternal Law.

Is the film a celebration of a return to primeval forces repressed by modern society? Or is it, rather, a film that dramatises the catastrophic effects of secularisation as various destructive beliefs and new ageisms replace the Judeo-Christian tradition? When Christianity — the symbolic Law of the Western world — fails, argues Žižek, it creates a vacuum for the emergence of primordialism. He asks further: ‘When the Taliban forces in Afghanistan destroyed the Bamiyan statues, were we, the benevolent Western observers outraged at this horror, not all Dysarts?’ The suggestion seems to be that having toppled dictators and encouraged the spread of ‘democracy’, the West created a space for the emergence of Isis and the Taliban. But Zizek’s argument is more disturbing than this. He is wondering: as members of the largely secular West observe the Taliban, do we secretly admire their willingness to believe in something?

What that something should be, or might be, is a topic of some discussion in allegorical readings of Equus. Alan’s horse-worship has been read in many ways, with several suggesting that the play is really about repressed homosexual desire. To read the play in relation to Richard Burton’s own life is to offer an alternative interpretation. The prior, primordial culture for Burton was the Welsh speaking, nonconformist religious world of his earliest years in Pontrhydyfen. There is a suggestion in the play itself that Dysart, due to his ethnicity, is particularly appropriate as a psychiatrist for the boy. When Hesther, the lawyer, brings the case to Dysart he doesn’t want to take it on:

DYSART: May I remind you I share this room with two highly competent psychiatrists?

HESTHER: Bennett and Thoroughgood. They’ll be as shocked as the public.

DYSART: That’s an absolutely unwarrantable statement.

HESTHER: Oh, they’ll be cool and exact. And underneath they’ll be revolted, and immovably English. Just like my bench.

DYSART: Well, what am I? Polynesian?

HESTHER: You know exactly what I mean! … [Pause] Please, Martin. It’s vital. You’re this boy’s only chance.

It is not clear what Hesther means. Dysart is a Scottish name, though the psychiatrist’s nationality is never raised in the play. Dysart may be based on the Scottish psycho-analyst R. D. Laing (1927-1989), whose The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness (1960) influenced Shaffer (and would form the theoretical basis for David Holbrook’s controversial reading of Dylan Thomas in The Code of Night (1972)). But having Burton play Dysart gives this scene a Welsh subtext. The suggestion seems to be that the not wholly modern, not wholly civilized, ‘Celt’ may have some understanding of Alan’s primordial horse cult.

Burton chose to perform Equus in the 70s, a period where he was inclined to describe his life and career in terms of the sterility that Dysart also identifies and rails against in his own life. This is Burton in a diary entry of August 1971:

My lack of interest in my own career, past, present or future, is almost total. All my life I think I have been secretly ashamed of being an actor and the older I get the more ashamed I get. […] And I think it resolves itself into a firm belief that the person who’s doing the acting is somebody else.

Shaffer’s play may be seen to speak to this predicament of the divided self. The play is clearly highly Lawrentian, but here — unlike D. H. Lawrence’s St Mawr (1925), which is also a tale about a horse and the repression of primordial forces — the psychiatrist is in the play, the interpreter is in the text. Equus is a postmodern play in the sense that it is being analysed as it is being performed. And in this self-reflexive process, in this turning in on itself, it’s hard not to apply Dysart’s growing self-awareness and frustration back onto Richard Burton himself.

In an interview with the film director Tony Palmer, Burton recalls trying to change the tone of his voice and his accent while under the tutelage of Philip Burton. After his classes, Richard would walk to the top of the mountain above Tai Bach and scream loudly until his voice lost all of its natural characteristics. This act of destruction would allow for reconstruction. Is this not the scream of an individual being deprived of his culture? Although he mastered Shakespearean and Hollywood English, and stepped onto the international stage, wouldn’t that scream echo as a kind of internal voice of resistance, a trace of his formative self, throughout Burton’s life? In becoming Richard Burton, Richard Jenkins was undergoing — in a stark and dramatic form — a process of cultural assimilation that would define twentieth-century Wales. It is a process that he explored in allegorical and metaphorical terms in Equus. As Dysart / Burton asks of us: ‘Can you think of anything worse one can do to anybody than take away their religion?’

Daniel G. Williams is Professor of English Literature and Director of the Richard Burton Centre for the Study of Wales at Swansea University.

To find out more about the ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ exhibition, visit the National Museum Cardiff website here.

Equus