With the ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ / ‘Bywyd Richard Burton’ series due to re-open at the National Museum Wales, Wales Arts Review is publishing a series of essays to run concurrently with the exhibition, curated by Daniel G. Williams, director of the Richard Burton Centre at Swansea University. Each essay will discuss a specific Burton film; today, Dr Richard Robinson takes a look at The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

‘We are what we pretend to be’

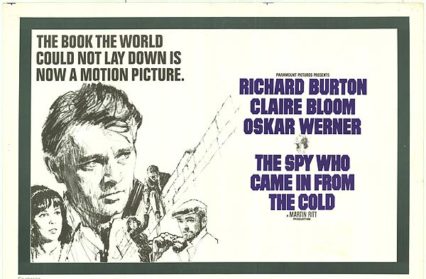

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) was John le Carré’s third novel and it made his name, allowing him to leave the MI6, for whom he had been working in Germany. I have a Victor Gollancz copy, published a few months after the first edition and priced at 18 shillings, which has already run to an eighth impression. The novel was soon made into a Paramount film in 1965, directed by the American Martin Ritt, who had just made Hud with Paul Newman, and starring Richard Burton in the role of Alec Leamas, the hard-bitten spy on his last mission. It is surely one of Burton’s finest screen roles: he was nominated for an Oscar, but lost out to Lee Marvin in Cat Ballou — one of those not so irregular Academy oddities.

It might have been very different. Le Carré had originally thought of Peter Finch or Trevor Howard, while Ritt had the idea of making Leamas into a Canadian so that he could be played by Burt Lancaster. And even once Richard Burton had been cast, both Ritt and le Carré wondered whether his fulminating theatrical personality could be contained in this film. Would he be able to play the downbeat operative, or submit to this pared down, distinctly un-epic form? In his essay ‘The Spy who Liked Me’, le Carré puts the question in vivid terms:

How on earth will this beautiful, thunderous, baritone Welsh voice and this overpowering triple Alpha Male talent fit inside the character of a washed-up, middle-aged British spy not noted for his charisma, his classic articulation, or the looks of a pockmarked Greek god?

There was a great deal of creative tension between the director, a former Communist sympathiser (or ‘fellow traveller’) who had been blacklisted during McCarthyism, and the starry actor, but out of this conflict emerges a performance of balance, of power and constraint. That baritone unforgettably still sings out lines such as ‘Who the hell do you think spies are?… they’re just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me’, and yet Richard Burton exploits silence and close-up, too: the camera lingers on the ‘pockmarked’ face of the spy, a professional mask which slips, registering scorn, outrage and the anguish of betrayal.

There is a gossipy relish in le Carré’s account of the shooting of The Spy in the Ardmore studios in Ireland. Richard Burton had just married (for the first time) Liz Taylor, who would arrive on the shoot in a white Rolls-Royce, perhaps accompanied by Yul Brynner, perhaps by Franco Zeffirelli. The seventeen-strong Burton-Taylor household occupied the whole floor of Dublin’s grandest hotel. Meanwhile Claire Bloom, who plays Leamas’ Communist lover Nan Perry and with whom Burton had had a fling in the 1950s, remained in her caravan between love scenes. Unsurprisingly, Burton was drinking heavily on set. This induces a self-referential, Russian doll effect: a heavy-drinking actor is playing the role of an able spy who is knowingly playing the role of a drunken man gone to seed; the life of the faux defector and the actor are increasingly indistinguishable through the bottom of a glass.

Le Carré commented that the film’s ‘grim black and white … wasn’t what we were wearing in 1965’. Cinema was ‘wearing’ colour, no more so than in the Bond films; we may think of the gold sheen of Goldfinger, which was released the year before, or the snazzy direction of The Ipcress File, whose alternative Bond, the anti-establishment Harry Palmer, was the perfect vehicle for Michael Caine’s working-class cool. But in The Spy, cinematographer Oswald Morris’s play of light and shadow, such as in the ‘artificial moonlight’ of the Checkpoint Charlie searchlight, or those chiaroscuro scenes in unadorned rooms with bare bulbs, is well suited to a starkly monochrome theatre. The border zone is aestheticised in the prose of the novel, described as ‘a half-world of ruin, drawn in two dimensions’, indeed as an ‘empty stage’, as if the Cold War thriller is being played out in a denuded Beckettian setting. The film emblematises le Carré’s deglamourising of the spy: our immersion in the technical business of spycraft does not disguise a broader evocation of existential loneliness — of what it is to operate ‘in the cold’, perennially sceptical about one’s fellow human beings, compelled to live without sympathy.

J.B. Priestley praised the film for being ‘superbly constructed’ and there is a dramaturgic symmetry and unity to The Spy, which starts and ends at the border, crossing it about half-way through. Graham Greene rated le Carré’s book the best spy novel he had read. For Greene the border, in the words of Robert Browning he liked to quote, was that ‘dangerous edge of things’ where we may find morally ambiguous characters — ‘the honest thief, the tender murderer, the superstitious atheist’. The Third Man, Carol Reed’s earlier film written by Greene, takes place in an occupied post-war Vienna quartered between the Allies, a ruined capital casting long shadows and expressionistically framed in canted angles. The aesthetic attractions of the geopolitical dividing line (its wall, its ‘curtain’) are also apparent in The Spy’s Berlin, and so too is the penetrating moral enquiry brought into relief by such dangerous liminality. Safe in London, the Head of the British Secret Service (the ‘Circus’), the suave and aptly named Control, concedes that though the ideological ideals of east and west may be diametrically opposed, supposedly black and white, the methods are the same. The Cold War is a looking-glass world, in which one side perfectly reflects its anti-world and the notion of an authentic unitary self is destabilised. The agent of the ‘Circus’ is always threatened by a political counterpart, an unseen doppelgänger on the other side.

From our vantage point of 2021, we see the important proximity of the Cold War to the Second World War. Leamas makes the argument in the novel, if not the film, that the small-scale conflicts of divided Europe are nothing like world or nuclear war. But even if the Cold War seems like a necessary evil which allows civilians to sleep peacefully, it is difficult to take much comfort. The focus is on who is sacrificed in this miniature war, this deterrent war-by-proxy. Leamas refers to driving on an Autobahn, seeing children waving in a small car which is about to be caught between two pantechnicons, suggesting the innocents who will be crushed between eastern and western blocs. In this ideological face-off between capitalism and communism, can ‘we’ in the west can be sure of our moral rightness? Control claims that ‘our’ policy is benevolent — but can the dirty means of spycraft be reconciled with the glorious ends of liberal democracy? The fall of the wall which le Carré saw erected in 1961 did not guarantee the end of history, in Francis Fukuyama’s now maligned term, but rather that Marx’s restless spectres would return to walk in new clothes.

Indeed the film shows us how the ghosts of the Second World War, in particular, have not yet been exorcised. The director Martin Ritt referred often to his own Jewishness, and this emerges a key subtext to the film. One of the protagonists is Comrade Fiedler, second-in-command in the Abteilung (the east German secret service), a Communist who is also Jew. This is a curiosity in post-Nazi Germany, explained by the fact that Fielder, the impassioned ideologue, has returned to Germany from Canadian exile in order to remake Germany — or at least the German Democratic Republic — as a model socialist state. However, Fiedler’s antagonist is Mundt, a former member of the Hitler youth. The Second World War is transposed to the Cold War. The Jew, once again, is sacrificed to the Nazi.

Jewishness also figures mysteriously in the casting of the film. Burton and Taylor would argue light-heartedly about who was the more Jewish. Taylor had converted to Judaism in her twenties. Burton claimed he had Jewish ancestry (incorrectly, it seems), and would say that the Welsh were the ‘Jews of Britain’. He wanted Taylor to be cast in the film but Claire Bloom, a Jewish British actress who later married the American writer Philip Roth, was chosen instead. However, the character in the novel of the Jewish Communist Liz Gold is renamed as Nan Perry in the film — a decision not only to avoid the inevitable ‘Liz’ connotations but also to make her less Jewish, something which puzzled le Carré.

A nerdish delight is to be had in recognising a host of familiar supporting actors: Bernard Lee (or ‘M’ from the Bond films); Michael Hordern playing the shifty Ashe (with a dubious ‘e’); a young and contemptuous Robert Hardy (both Hordern and Hardy were friends of Richard Burton). The Irish actor Cyril Cusack is cleverly cast as Control, and is the epitome of donnish froideur, apparently placing as much importance on the brewing of tea as on the loss of agents in the field. Oskar Werner, an Austrian actor who had starred in François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim, won a Golden Globe for best supporting actor performance as the ‘clever Jew’ (Burton spits out those words, implicitly condemning the persistence of anti-semitism). And as another of the intermediary operatives, Peters, there is Sam Wanamaker, the American-born actor who like Ritt fell foul of McCarthyism, and whose brainchild it was to rebuild the Globe theatre on London’s South Bank. There is even the briefest of non-speaking parts for Warren Mitchell (or ‘Alf Garnett’), another of Burton’s friends.

The novel and film ask us to assess the value of loyalty — to a country, to a cause, to oneself — and to the bloodless manipulation of such loyalty. Le Carré, recruited as a spy himself while at Oxford and briefly a master at Eton, knew the establishment from the inside, and knew about its secrecy, its capacity both for self-protection and treachery. This is the time of the Profumo affair, when the hierarchical old order, represented by the likes of old Etonian Prime Ministers (Harold Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home), were about to be swept away — for the time being. The public were becoming less deferential, and were enjoying the satirical eviscerations of TV programmes, such as That Was the Week that Was, that exposed the flagrant duplicity of the establishment. Social pretence was consonant with the treacherous double-dealing of espionage in the Cold War, as the painfully slow unmasking of the Cambridge spies reveals. In a novel by Kurt Vonnegut published at around the same time as le Carré’s, Mother Night, an American brought up in interwar Germany and supposedly recruited as a American double agent ends up being tried as a Nazi propagandist. Vonnegut does not naively yearn for authenticity, though, concluding that ‘we are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be’. In le Carré’s looking-glass world, too, Burton’s performance shows us that pretence, that stock-in-trade of both spy and actor, is a potentially treacherous moral commitment that we are compelled to make.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold

Dr Richard Robinson is Associate Professor of English Literature at Swansea University.

To read the first essay of Becoming Richard Burton series, click here.