Ceri Subbe explores a national obsession with memory through the lens of the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ mural, making the case for a form of cultural amnesia which might enable Wales to formulate a more positive sense of national identity.

What exactly are the Welsh being asked to remember when confronted with this mural? The injustice of colonisation? The shame of complicity? Victimisation? All bitter evocations which form an unhealthy foundation for national identity. Growing up in northwest Wales, I have always been acutely aware of this subordinate identity, laying the blame for many an injustice at the door of English oppression. But the older I get, the more this feels like blaming your parents for anything after the age of thirty – you just can’t do it anymore.

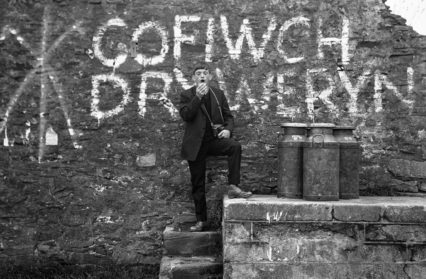

I have found it difficult to form new ideas around national identity when the burden of memory is so prevalent in Welsh culture. Nothing symbolises the Welsh national obsession with memory better than the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ mural, which has been appearing with increased frequency up and down the country recently. The command to remember the vanished community of Capel Celyn, drowned in 1965 to create a reservoir to supply water for the industrial expansion of Liverpool, is, at times, oppressive. The impact of this controversial command on present-day Wales, taking into account Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the surgency in second home ownership, has been a re-enforcement of devolved four-nation national identities over the past couple of years. Unfortunately, the connotations are often negative, stirring old anger around colonisation and oppression of values and traditions. But is this reluctance to forget a necessary form of social glue, bringing people together in a cohesive force which gives a narrative shape to trauma, or is memory a toxic energy which would be better spent championing present-day and future issues which face the nation?

Memory is the struggle against forgetting, and can be a double edged sword. Nietzsche revolted against the intolerable burden of memory and recommended the forgetting of history, which becomes more and more complex over time so that the sheer task of remembrance causes the historian to lose the ability to act and to live in the present. Milan Kundera, on the other hand, saw memory as a painful responsibility, a moral and ethical act which intensifies human relationships and creates cohesive bonds within groups that have shared a past. Somewhere between Nietzsche and Kundera lies a healthy balance between collective national memory, and a forgetting which does not amount to treachery.

We do not remember alone. National identity is informed within group structures, and is supported by external frameworks created by those who claim to speak for the collective, including writers, artists, and politicians. Shared memory is used to uphold the characteristics of group identity, creating a sense of stability and belonging to those within the group. But does this lead to the tribal exclusion of people who are on the outside of this group? The danger is that clinging on to traumatic memory is detrimental to the creation of a more positive and diverse collective outlook.

The Welsh have invested much of our national memory in trauma and landscape. Trauma lies in the external force of colonisation of language and culture, whilst exploitation of landscape through industry and tourism has an element of internal complicity in allowing such developments to happen. Much of mythological Wales is embedded in landscape, which means that any attack on it feels viscerally personal. According to Simon Schama, national identity ‘would lose much of its ferocious enchantment without the mystique of a particular landscape tradition: its topography mapped, elaborated, and enriched as a homeland.’ Subsequently, industrialisation, deforestation, quarries, reservoirs all contribute to physical alterations in the national psyche. Ned Thomas explains that ‘one should not underestimate what it means to live in a country where fields and rivers and hills and villages conserve old human feelings.’

All of the above culminate in the Tryweryn affair being the perfect storm of exploitation from without, and a lack of momentum from within to prevent the reservoir being built. The residual national memory resulting from this is subsequently confusing, and it is therefore curious that some Welsh communities have adopted the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ slogan as a present-day memo because its connotations are not straightforwardly nationalistic.

I have found that R. S. Thomas’s poetry of the 1960’s and early 70’s captures the sense of Welsh shame in selling out, and I have always felt a particular kind of discomfort when reading it, the kind of discomfort I guess one feels when confronted with some kind of truth. Earlier in his career, Thomas used gothic tropes such as haunted fortresses and eerie abandoned industrial sites to characterise a land of decaying memories, ‘Brittle with relics’, to convey a haunted nation. His mute prototype of the Welsh peasant hill farmer, Iago Prytherch, is a ghostly representation of a people no longer present, or in fact, who may never have been present in the first place. When infused with the nationalist political landscape of the 60s through to the 1979 Referendum on Welsh independence, the writing becomes altogether more accusatory, the poet turning in on his own people. ‘Reservoirs’ from Thomas’s 1968 collection Not That He Brought Flowers is an example:

Reservoirs

There are places in Wales I don’t go:

Reservoirs that are the subconscious

Of a people, troubled far down

With gravestones, chapels, villages even;

The serenity of their expression

Revolts me, it is a pose

For strangers, a watercolour’s appeal

To the mass, instead of the poem’s

Harsher conditions. There are the hills,

Too; gardens gone under the scum

Of the forests; and the smashed faces

Of the farms with the stone trickle

Of their tears down the hills’ side.

Where can I go, then, from the smell

Of decay, from the putrefying of a dead

Nation? I have walked the shore

For an hour and seen the English

Scavenging among the remains

Of our culture, covering the sand

Like the tide and, with the roughness

Of the tide, elbowing our language

Into the grave that we have dug for it.

Shame and complicity emanate from this poem, a personal moral despair synonymous with self-loathing. The tonal bitterness creating the stench of decay is so darkly pessimistic that it is more of an elegy than a protest, a shackle of memory around the nation’s ankle. If this is the kind of remembering triggered by the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ mural, it can be described as maddening, even pathological. I have often wondered how much responsibility poets, writers and artists should take for the seepage of this kind of narrative into the subconscious, both personal and national, and the consequences that follow. Yeats had an, albeit very late, attack of moral responsibility when he asked: ‘Did that play of mine send out / Certain men the English shot?’. Too little too late by Yeats there perhaps, but a prompt for contemporary poets to have an awareness of consequence.

Toni Morrison’s work contains more accessible ways of giving shape to national trauma. The context of slavery is, of course, very different to the predicament of English oppression of the Welsh, but – in the way she deals with recollection – the act of remembering is somehow more honest, more communal. Instead of harsh instructions to remember, Morrison’s characters seem to realise the power that can be gleaned from shared collective memory. I am thinking in particular of her masterpiece novel Beloved, where the ghost of a child born and killed in slavery, must be acknowledged and exorcised before the community can begin to move on. Morrison explores transgenerational healing through reconstructions of past events, recalling any positive aspects if at all possible. Sethe, the bereaved mother at the heart of the novel comes to realise that shared narrative is the only way to heal: ‘Her story was bearable because it was his as well – to tell, to refine and tell again’. ‘Sethe,’ her husband tells her, ‘me and you, we got more yesterday than anybody. We need some kind of tomorrow.’ Can it be that the Welsh need to re-group to refine our national identity – seek out new positives and new possibilities? A new balance needs to be struck between our shared past, and a necessary form of cultural amnesia.

Forgetting is an inseparable component of memory itself, it is crucial in the future trajectory of what we chose to remember. The balancing act between remembering the importance of shared cultural history and trauma leading to collective solidarity, with a process of collective amnesia which relieves over-burdening, is the central conundrum of national identity for many countries.

The Referendum in Wales in 1979 was a crisis point of national identity. Some heavy-duty remembering had been called to action in an attempt to secure a vote for independence. Saunders Lewis’s ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ speech, the formation of Cymdeithas yr Iaith, the Tryweryn affair all culminated in a national mood of bitterness driving devolved power, which was ultimately ill-fated. The nationalist movement was unsuccessful in part due to support across south Wales for the Labour party with figures such as Neil Kinnock being strongly unionist. This led to an internal difference in Wales which weakened the country as a whole, the nation being less effective than the sum of its part.

Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic appear to have awakened a muscle memory of the emotional baggage associated with the trauma of the Referendum, thwarting any attempts to forget. The pandemic gave the four nations an opportunity to assert their devolved power, in particular, the way they went into and out of various lockdowns, their policies around keeping the nations safe in terms of mask wearing, social distancing etc. Who can forget the tempered relish with which Nicola Sturgeon and Mark Drakeford stood on their podiums and took swipes at Boris Johnson’s chaotic approach, seeding a new appetite for nationalism. As someone who worked on the frontline of acute care in my local hospital during the pandemic, I found the resentment politics being played out both insensitive and distasteful in light of the wave of grief that was sweeping the nations. Never had the need for a more mature political model of functional collaboration seemed so necessary.

Similarly, Brexit resurged nationalist forces. The abominable disregard shown by Westminster to the Good Friday Peace agreement in Northern Ireland, which was fought for so skilfully, so passionately by some of history’s most accomplished negotiators, is fuel for any fire which seeks independence from London centrism.

Interestingly, many voters who are pro-independence are also anti-Brexit. Breaking away from the United Kingdom, but remaining European, seems to be desirable. Could it be that Europe recognises and respects smaller nations in a way that London simply does not? In terms of Welsh nationalism, and the undeniable surge in the prominence of ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ graffiti, is indicative of a nation that has found a way to carry out what Paul Ricoeur describes as ‘a forgetting in reserve’, a ‘mode of forgetting which holds the past in reserve rather than erasing it entirely’. Perhaps this is the way to move towards a healthier cultural and personal approach to the past, with memory and forgetting being fluid entities, capable of being called to action or laid dormant as the situation requires.

Fictional characters such as Niall Griffiths’s Ianto from Sheepshagger embody what it is to be a nation who has forgotten its own history, and the resulting fear that not belonging to a community, even a traumatised one – which can be disorientating and harmful to the individual spirit – can be. If we consider the trajectory from Iago to Ianto, it is a one of silencing, frustration, and dehumanisation. From the ghostly hill farmer with the faint remnants of tradition, through to a muted, violent delinquent that is Ianto, the mental anguish is inversely proportional to lack of purpose. Ianto is devoid of any distinguishable voice, unable to speak for himself, and nobody able to speak authentically for him. Trapped in a lost generation who are not old enough to identify with the perceived glory days of industrialisation, agriculture and Welsh language fluency, and yet are too young to have any real influence on current day national politics which is largely out of their hands anyway as so much of it has been handed over to Westminster exteriorly and prostituted out interiorly by complicit situations such as second home ownership. Ianto has no language which speaks to him, the Welsh language has not been gifted to him, and his poor education means that he does not have a mastery of the English language of the coloniser, either. The result is a primal scream of frustration. As a consequence of the Welsh forgetting, or selling out, their culture – the language, landscape, education and history – it is perceived by Ianto’s generation that the Welsh have lost control of their tools of self-definition. As described by Ngūgi Wa Thiong’o in Decolonising the Mind,

Language carries culture, and culture carries, particularly through orature

and literature, the entire body of values by which we come to perceive

ourselves and our place in the world. How people perceive themselves

affects how they look at their culture, at their politics and social production

of wealth, at their entire relationship to nature and to other beings. Language

is thus inseparable from ourselves as a community of human beings with a

specific form and character, a specific history, a specific relationship to the world.

Colonisation functions through the undervaluing of a people’s culture, and an elevation of the language and customs of the coloniser. These new forms of communication can never truly reflect the intricate inner workings of an individual or a community, and the subject is permanently subjected to misrepresentation and voicelessness once deprived of the specificity of cultural images of the World and of the Self, contained within colloquial narrative. Once people’s memory and belief in their own names, language and environment is annihilated, the process of degradation has begun, and the resulting despondency and despair, as embodied in Ianto, sets off a form of cultural suicide. We are nobody, after all, if not heard.

Another inarticulate, abused and frustrated fictional character who is lost in a post-industrial legacy of south Wales is Rachel Tresize’s female protagonist in her novel in and out of the goldfish bowl. The novel is set in the economic depression which hit Rhondda in the 1980s as a community in crisis grapples with the poverty, toxic masculinity, and emptiness resulting from unemployment and a loss of identity. Like Griffiths, Tresize encapsulates lives haunted by trauma – postcolonial trauma, post-industrial trauma, personal trauma – all the product of accelerated modernisation, poverty, and destroyed traditions. Both authors are dealing with more than the issue of fragmented Welsh national identity, they are dealing with the issues which often become entangled and inseparable from national identity such as class, gender, industry. The issue of second home ownership, for example, is a class issue. A capitalist economic landscape which allows a percentage of the population to be wealthy enough to own a second home whilst most working people are barely able to afford one home, can only be an issue around social class. However, pockets of Welsh society have attributed this economic situation to colonial exploitation from over the border, and have attached the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ motif to the situation. This is neither appropriate nor correct, and must be confusing to the Welsh youth who are attempting to assert their own identity, a hybrid identity based on wonderfully blended communities where speaking the language or direct Welsh genetic lineage are not essential, but are being held back by past trauma. Letting the past stand in the way of progress can potentially lead to an immobilising cultural inertia. An exercise in forgiveness – forgiveness from within, acknowledging Welsh shortcomings to protect its own culture, and forgiveness from without, acknowledging the injustices of English oppression – may be a way forward. Pure forgiveness of the unforgivable is beyond what is expected, but relieving present-day Wales of some of the trauma of the past could be crucial in the creation of a more positive sense of individual and collective identity.

There is a case to be made for the queering of national identity, that is, adopting a postcolonial fluidity and acceptance of change, rather than a dangerously narrow adherence to binaries – the sense of being one thing because you are not the other. Being defined on such negative terms promotes otherness, but most sadly, cripples any sense of progress towards hybridity.

The ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ mural is a usable motif for shared national identity and traumatic memory that can be called upon in times of crisis, but only to a certain extent. It is difficult to move on from suffering if that suffering goes unacknowledged, and so collective describing and processing of harrowing experiences can facilitate healing, but can also lead to obsessive impulses to over-burden the past on the present. It is therefore wise to keep shared socio-historical memories as a reserve bank of memory that can be accessed at times when national identity feels under threat of fragmentation either from an assault from within or from without. Brexit and the Covid 19 pandemic are two such assaults which have prompted a re-evaluation of Welshness, only to land at the same questions as we always land on: we are an exploited, colonised people who have had their culture and customs oppressed by the English – and what are we going to do about this?

With regards to forgetting, it has its importance in the facilitation of national memory. The shame of forgetting is used as ammunition at times of political jeopardy, the nation turning in on itself to prompt a certain response or a certain vote, usually against the English and pro-independence. However, a balance needs to be struck between the crippling obsession placed by some nationalists on remembering trauma, and exercising a ‘forgetting in reserve’ which allows memories to be accessed as situations demand. It is impossible for any nation to exist in a completely tensionless state with no trauma and a mental hygiene which evades even the most pacifist countries. Forgotten heritage can lead to an existential vacuum such as that embodied by Niall Griffiths’s symbolic fictional character Ianto. R. S. Thomas’s Iago, however, is also in this vacuum, trying to uphold a version of the past which is no longer compatible with present-day Wales. Each generation must work its own way through its own version of collective neurosis. Perhaps ours will be Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic, the failure of the Good Friday agreement in Northern Ireland, and the very real possibility of Scottish independence the next time the nation takes to the polls. Whatever form the neurosis takes, care must be taken with regards to the moral and ethical dimensions of recollection and the impact the past has on the present, and the present on the future.

Both individuals and collective peoples have an obligation to remember responsibly, and to explore the possibility of forgiveness. Forgiveness allows for the recognition and acknowledgement of past injustices, a describing and understanding of these injustices, before finally either fully or partially releasing these emotions to make way for new thoughts around identity evolution.

Finally, a note on how we remember today. Obsessive digital over-archiving on social media may contribute to the degradation of the process of remembering. As memory becomes unmappable and algorhythmical, are we losing the ability to engage with the past because of the transient nature of cyberspace, and therefore need concrete motifs such as the ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ mural to provide a reference point for identity?

Ultimately, the most important faculty on the sliding scale of memory and forgetting is for individuals and communities to move beyond any label, asserting control and fluidity in equal measure. To achieve this, cultural engagement is essential – it is the role of artists, writers, and anybody immersed in the arts to help mould a new, confident, version of national identity. This kind of engagement would certainly have helped me growing up in trying to make sense of an inherited cultural negativity which I only much later had the sufficient sense of awareness to challenge. There is a line at the end of in and out of the goldfish bowl where the protagonist, who has survived extensive personal trauma, witnesses the death of her much-loved grandmother. This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the necessity of storytelling, mining the past for what it’s worth, before embracing a forward momentum towards something healthier:

My Gran died the following Tuesday, as planned, yet she gave me

more than a choice of clothes and a sewing machine, she gave me the

person who is writing this sentence. She gave me treasured stories and

standards to live by, reasons to fight my way to where I want to go.

Photo credit: alh1 via Flickr.

Ceri Subbe is a PhD student in the Department of Welsh and Celtic Studies at Bangor University, having graduated prior to this with a first class honours BA in English Literature, and an MA in Welsh Writing in English, both at Bangor University. Alongside her doctorate studies, Ceri works as a physiotherapist specialising in palliative care having having graduated with a BSc in Physiotherapy from Cardiff University. She now enjoys writing as a form of escapism from what can be a challenging healthcare setting.