Jim Morphy visited the Hay Literary Festival to witness two talks by the award-winning travel writer Robert Macfarlane.

Holloway: Robert Macfarlane talks to Horatio Clare,

An Adventure: Artemis Cooper talks to Robert Macfarlane

The Drovers’ Roads of the Middle Marches, with Wayne Smith

‘Travel writers are great travel readers’, Robert Macfarlane tells us during one of the two talks he is involved in on the second Saturday of Hay. His fascinating discussions with Horatio Clare and Artemis Cooper prove this point, laden as they are with references to Macfarlane’s forbears in the ‘writing and nature game’, as he calls it.

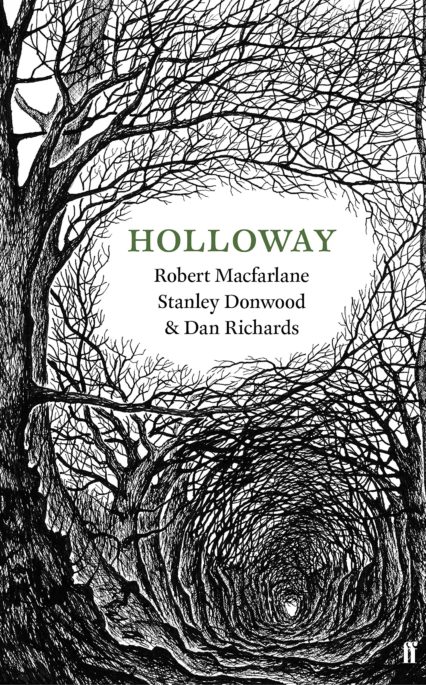

Macfarlane’s first talk concerns his latest effort, Holloway, which itself resulted from his interest in another book. In 2005, Macfarlane and Roger Deakin set out to find the Dorset holloway where the hero of Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (which, Macfarlane tells us, ‘is a great thriller and very weird’) hides from his evil pursuers. Six years later, after Deakin’s death, Macfarlane returned to the holloway with artist Stanley Donwood and Dan Richards (the book’s co-author). The slim, beautifully-produced Holloway is the result of their adventures.

Macfarlane’s first talk concerns his latest effort, Holloway, which itself resulted from his interest in another book. In 2005, Macfarlane and Roger Deakin set out to find the Dorset holloway where the hero of Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (which, Macfarlane tells us, ‘is a great thriller and very weird’) hides from his evil pursuers. Six years later, after Deakin’s death, Macfarlane returned to the holloway with artist Stanley Donwood and Dan Richards (the book’s co-author). The slim, beautifully-produced Holloway is the result of their adventures.

Robert Macfarlane describes Holloway as an ‘oblique’ and ‘echoic’ book. It is nearer to poetry than it is to Macfarlane’s previous book, the highly-acclaimed The Old Ways. Certainly, it’s a book that will divide opinion, as Macfarlane happily acknowledges.

Holloway is soaked in Macfarlane’s deep affection for ‘the childlike but not childlish’ Deakin. Deakin himself was a documentary maker and author of the best-seller Waterlog, a book about wild swimming in Britain’s rivers and lakes.

Macfarlane tells us that it was Deakin’s influence that turned his interest away from famous mountaineering sites and towards Britain’s barren moors, hidden corners and beaten footpaths. Macfarlane says this change in attitude can be seen in the change in altitude of his books, from his debut Mountains of the Mind, through The Wild Places and The Old Ways, then to the sunken Holloway, and now onto his next book, which is to be about the caves, sinkholes, and the like, beneath the ground.

Macfarlane’s talk with Artemis Cooper takes the latter’s highly-acclaimed biography of soldier/travel writer/charmer Patrick Leigh Fermor as its starting point. Macfarlane had told us earlier than Fermor is the kind of travel writer that you read and think: what’s the point in me writing? I’ll never write anything as good as that. He is the best, they think. Macfarlane’s and Cooper’s affection for Fermor shines through in the talk. In fact, the love-in gets a tad sickening at times.

Fermor’s writings, we’re told, focus on the external adventure of it all: always looking out for, and telling us about, the next person on the path, the next drink, the next change in the landscape, the next group meal. Fermor was not one for analysis. Cooper tells us Macfarlane gives us more of the internal reflection and the physical ‘step by step’ of walking: the thoughts, the tiredness, the blisters, the bad night’s sleep under the stars.

Paddy’s writing has lots of active verbs, is very descriptive and extravagant (not least with the truth), Macfarlane says of Fermor. Our two hosts compare this approach to that of Bruce Chatwin, famed for his short descriptions and ‘packing it all down’.

Travel writing has changed greatly since Fermor and Chatwin, we’re told. Like the novel, this genre is always supposedly dying but actually is always being reborn.

Much previous travel literature now looks horribly dated with its colonial outlook and notions of discovery, they say. Certainly, there’s nowhere left to be ‘discovered’ now. The future of travel-writing, Cooper suggests, is in exploring both the landscape and the mental reflection that walking brings, much in the way that Macfarlane’s wonderful The Old Ways does. That book would seem to be the one for the rest to follow.

Earlier in the day, Wayne Smith had given us an entertaining talk about his debut book, The Drovers’ Roads of the Middle Marches. Smith describes himself as a hobbyist, and the enthusiastic spirit of the amateur shines through in both his book and his talk. In fact, it’s entirely charming to see someone so clearly delighted – and perhaps a little surprised – to have a book out and a full audience to talk to about it. Smith jokingly tells us he suffers from Obsessive Compulsive List Disorder. His frame of reference comes from OS maps, Wainwright’s Walks, the CAMRA guide to pubs, the guide to Wales’s 100 best churches, and the like. This is in contrast to the distinctly literary efforts of people such as TS Eliot, Descartes and Robert Frost that peppered the talks of Robert Macfarlane. Neither speaker suffers in this comparison. Apples and pears, and all that.

The Drovers’ Roads of the Middle Marches includes a history of the tracks, tips on finding ‘hidden’ ones, and a number of suggested circular walks. It would seem a good purchase for those keen to get their hiking boots on.

Travel writing can disappear into the abyss when it is constantly reflecting on other books, Macfarlane tells us (and it would seem Snowdon’s author Jim Perrin has pretty much laid this charge at Macfarlane himself). But, without doubt, travel and nature reading and walking go hand-in-hand, enhancing the experience of each other. And these three talks at Hay certainly gave us enough ideas for books to weigh down the rucksack.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis