Next year, you won’t be able to avoid the fact of its being the centenary of one of Wales’ greatest writers; this year, you’d be forgiven for never having heard of at least one of the other two centenarians in question. One wonders, on having listened to Carolyn Hitt’s sharp, succinct documentary on the BBC Radio Wales Arts Show, whether Wales might not have its Thomases the wrong way around.

The programme finishes with Dai Smith, partly responsible for the recent revival of interest in Gwyn Thomas and his work in his role as Series Editor of the Library of Wales, claiming the author as ‘one of our own’. The man introduced at the top of the show as ‘novelist, playwright, short story writer, columnist, essayist, broadcaster and all-round raconteur’ would surely make a much better emblem – if we do indeed have to have one – of Welsh artistic culture than the already overexposed live-fast die-young boy-genius of Cwmdonkin Drive.

Gwyn, we learn, ‘embodied the Valleys values’ that fellow miserable-at-Oxford sometime Western Mail columnist Carolyn Hitt says she stands by. A Rhondda native herself, like many of us, Hitt has despaired at recent portrayals of the South Wales Valleys, whether the grotesque caricatures of MTV or the patronising bleakness of Mark Easton. Gwyn Thomas might well have despaired of the breakdown of the social fabric that has led to these portrayals, but also, at least on the evidence of this programme, one feels he might have had something positive and incisive, not to mention witty, to say about the situation.

For Gwyn, revealed to be both a product of and exception to his humble background, ‘education is sacred’. His twenty years as a teacher of Spanish, mainly in Barry, despite his later, mischievous proclamation that ‘I didn’t want to teach and they didn’t want to learn’ are characterised as ‘the central chunk’ of a life, a time ‘full of happiness’. That had certainly not been his experience at Oxford – ‘the Oxford of Brideshead Revisited’ as M Wynn Thomas reminds us in one of many fascinating insights – where Gwyn found himself spending a miserable three years. ‘Nothing ever hurt me quite as violently,’ Thomas recalled years later, his raw intellectual talent having lifted him, much in the manner of Dickensian melodrama (‘the very stuff of this life’), from the mining village of Cymmer in what is still one of Britain’s poorest regions, to what he described as the ‘glacial peaks’ of the world’s oldest and most prestigious university.

There was perhaps undoubtedly a melodrama at work in Thomas’ characterisation of the ‘frozen peaks of alienation’ he found at Oxford, where, he joked, he spent his time in the depths of despair, the university’s only saving grace – or, more likely, another curse – being the ‘long legs of infinitely tall Saxons’. For a miner’s son who had been brought up by an older sister, as one of twelve children, following the death of his mother when Gwyn was just six, and who often relied on the local soup kitchen for sustenance, the Oxford of champagne hedonism must have seemed a different world.

It seems that Gwyn retreated into himself, both at Oxford and during his year spent at the university of Madrid during the brief period of the Second Spanish Republic. M Wynn Thomas ruminates on the oddness of Thomas’ lack of engagement with the left-wing politics of Spain, but there is plenty of other evidence, particularly in his travels through the northern coal-mining valleys of Asturias, that Gwyn’s political outlook was being sharpened. Later, the parallels he saw between what was happening in Spain and in the Rhondda saw him draw a direct comparison between La Pasionaria and Lewis Jones. Once he was back among the people he openly called his own (Gwyn freely admitted to never being happy unless he was in the county of Glamorgan), he revealed himself to be ‘witty, literate and passionately political’.

Boyd Clack, who hails from Tonyrefail, a short walk from where Gwyn had grown up, characterised Thomas as ‘the go-to man when seeking the Welsh – particularly south Welsh – slant on things’. He remembers Thomas the broadcaster, the final ‘chunk’ in the man’s great Dickensian life. Through both written and spoken word and his ‘dazzling vocabulary’, Gwyn brought ‘Valleys culture to a worldwide audience’. He was, says Clack, echoing every other guest on the programme, ‘a genuine intellectual, a genuine talent.’ M Wynn Thomas perhaps sums it up best when he says that Gwyn was ‘educated yes – but educated so that he could become an eloquent spokesman for that culture with which he so strongly identified’.

What is interesting, in the context of recent debates in Wales Arts Review, is Thomas’ characterisation of South Wales society as a ‘warm soup of comradeship, love, singing, understanding’ – ‘interpenetrative, with a sensitive understanding of other people’s problems’. Though not a description that could genuinely be recognised today, the reawakening of Welsh culture outlined in these pages in recent weeks and months has at least challenged another longstanding idea. Clack talks of the ‘general acceptance that [people from South Wales] could never achieve anything’ and cites Gwyn as an example: ‘he proved that we could grab the world by the lapels’.

What comes through in anecdote after anecdote is that Gwyn, contemporary of Dylan, was of a completely different nature. Both writers, of course, were dazzling linguists as well as literateurs; they helped to give twentieth century Wales its reputation for wordsmithery in both written and spoken form, characterised by a mixture of fine oratory and a wicked sense of humour. It is interesting to compare the two men, not to use Gwyn as a stick with which to beat Dylan, but simply to view the different ways in which a Welsh inferiority complex can play out. On arriving at the offices of Victor Gollancz to discuss his first novel, Sorrow for Thy Sons, Gwyn had a panic attack and went home; he wasn’t published for a further ten years. By contrast, Dylan was published as a precocious teenager and among his first experiences in London was the infamous proposal to his friend Augustus John’s lover Caitlin MacNamara, putting his head in her lap in The Wheatsheaf on Rathbone Place.

The other thing that emerges in Hitt’s documentary is that Gwyn Thomas is a writer’s writer, a go-to man not just for television chat shows seeking a Welshman with penetrating insight shot through with humour, but for contemporary chroniclers like Rachel Trezise who sees an ability in her literary forebear to make readers cry and laugh ‘in the same sentence – in every sentence.’

Carolyn Hitt explores with Trezise the fact of, during their own Rhondda upbringings, Thomas’ work – despite the Library of Wales still much out of print – being unavailable in school. Trezise is not shy to admit that, until the much-heralded republication of The Dark Philosophers, she hadn’t even heard of Thomas. In her youthful naivety, she imagined herself the first writer from the Rhondda. The listener senses in her voice and in the avuncular tones of Dai Smith the cherishing of the connections being fostered between the writers of today and those still neglected voices of yesteryear.

The connection between past and present is only surpassed by the link, emphasised throughout, of literature and locality. Carolyn Hitt’s journey into the life and work of Gwyn Thomas is taken via Literature Wales’ tour ‘Riotous Rhondda’. All of her interviewees – most of whom are local – emphasise the personal connection they feel with the man because of where he came from; they play up his brand of humour and unique voice, which is nevertheless a representative one.

We do, of course, in Wales as elsewhere, rely on emblematic figures to tell others who we are. We have had more than our fair share of great cultural ambassadors in the fields of sport and music, stage and screen. As we gear up for 2014, representing ourselves through the life and work and legend of one great poet, it would be worth also ruing the opportunity missed this year to present ourselves as the country of Gwyn Thomas.

And as I reflect on the wisdom or otherwise of my own sometimes hasty contributions to the ‘eternal conversation’ of national debate, I find myself remembering a couple of Gwyn’s pearls of wisdom. His reaction, writing to a friend, on being afforded a weekly newspaper column is perhaps even more pertinent now than it was then. ‘What on earth has a civilized man to say to readers of a Sunday newspaper at seven-day intervals? And it has to do with ‘Welsh affairs’; there isn’t a Welsh affair in sight that isn’t black and blue from polemical flogging.’ And finally there is the encapsulation of Thomas’ philosophy, quoted in the final scene of National Theatre Wales’ much-lauded version of The Dark Philosophers: ‘If I ever had any philosophy to pass on to other people, it would be this: please do not regard any serious conception of yourself as having any true validity. We are all the victims of a big overriding joke.’

If Wales Arts Review is going to continue to foster – and I am sure that we are – the next steps in the ‘eternal conversation’, and perhaps even – who knows? – the next Gwyn Thomas, we would do well to keep these twin tenets in mind. To remember the tragic humour with which so much of life is infused, to remember that polemic should never be used for flogging, but most of all, perhaps, to remember, to celebrate, to cherish and to redevelop yet another positive Thomas saw in his beloved fellow countryfolk amid the challenges of his own era: ‘a great hunger for articulacy, for beauty, for being in the light’.

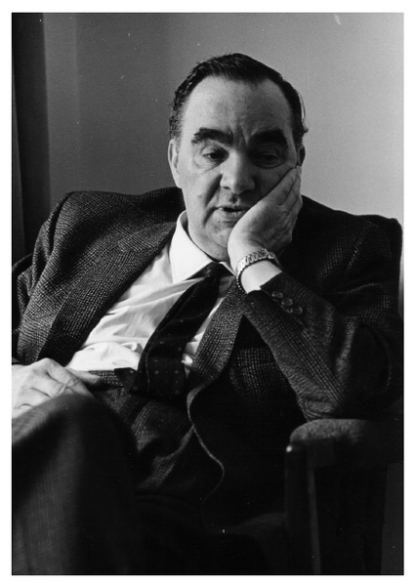

Anthony Hopkins as Gwyn in a television version of Thomas’ autobiography A Few Selected Exits (1993)

BBC Wales series, Welsh Greats, featuring Gwyn Thomas