From galleries to public art, Peter Wakelin takes a look back at some of the most significant moments in the last decade in the visual arts in Wales.

The terrible teens were a dreadful decade for culture, bludgeoned by austerity and menaced with the axe of Brexit. Slashed budgets cut into public provision of visual art just like other services. Nearly all galleries became less ambitious in their exhibition programmes, and their collecting for posterity withered nearly out of existence. Paradoxically, however, it seems that art, like life, will find a way. Many museums and galleries that looked like they might be forced to close in fact limped on, (apart from Bodelwyddan Castle, which closed in 2019). A few were even reinvigorated with schemes committed to before austerity dropped its guillotine. The economic climate for contemporary artists has been challenging but commercial galleries have opened and survived. So art has coped so far. Things might get worse still in the 2020s, but at the very least the Welsh Government’s nuanced distributed model for national investment in contemporary art raise a hope for better provision: they may make our institutions work together to serve the public across the country rather than stand on the false dignity of proud independence. Here’s a personal selection of the decade’s developments.

Refurbs and relocations

The teens have seen some striking investments in visual art venues and collections. The National Museum in Cardiff renovated the first floor of its west wing in 2011 to create a chain of white-box spaces that accommodate modern and contemporary art on a grand scale. Impressive exhibitions have included the David Nash retrospective in 2019, which triumphed in combining artistic quality with tremendous popular response. In 2016, Storiel in Bangor reopened after a major refurbishment and the Cardiff artists’ cooperative G39 moved from its city-centre terrace into a large modern warehouse. One of Wales’ best-loved galleries, the Glynn Vivian, reopened in 2016 with state-of-the-art new display spaces, educational resources and conservation facilities, showing a retrospective of the nonagenarian Swansea artist Glenys Cour. In 2019, two new models of art in the heart of the community have been tried – at Tŷ Pawb in Wrexham mixing art and small shops in the former market, and at Y Gaer in Brecon (formerly Brecknock Museum and Art Gallery) combining with the library after an eight-year refurbishment.

Commercial galleries

Alongside the public galleries, the private ones have kept artists in business. The Martin Tinney Gallery celebrated 25 years with an exhibition of important pictures which have passed through its hands since the beginning – including works by Gwen John, Cedric Morris and Ceri Richards and the contemporary artists it has supported such as Shani Rhys James, Sally Moore and Mary Lloyd Jones. Two even longer-established galleries have continued – the Albany in Cardiff and the Attic in Swansea (under new management for the first time in nearly sixty years). It’s been healthy to have some new players too. Arrivals have included Ffin y Parc in the Conwy valley and Gallery Ten in Cardiff, which like many galleries in the digital age has evolved from premises to pop-up.

Art publishing

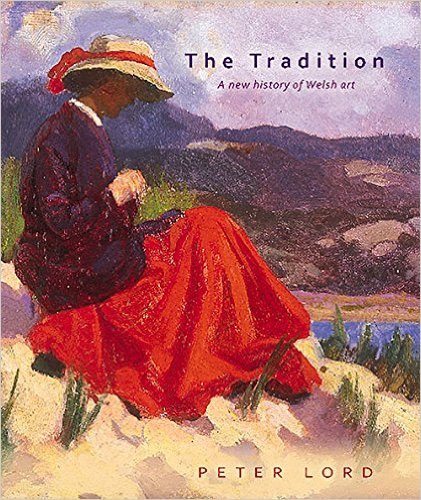

It doesn’t seem so long ago that books about Welsh art or artists were seriously scarce. That started changing in the 1990s but art publishing has burgeoned in this decade. Peter Lord’s new art history of Wales The Tradition provided a beautifully illustrated survey of art since the Reformation. The Buildings of Wales series filled the last gaps in its national coverage, and the Royal Society of Architects in Wales opened a series on Welsh architecture with John Hilling’s grand historical survey. A breathless list of monographs clarified the work and reputations of key Welsh artists, including Charles Burton, John Elwyn, Clive Hicks-Jenkins, Falcon Hildred, David Jones, Heinz Koppel, Sally Moore, Cedric Morris, Peter Prendergast, Edward Pugh, John Selway, Kevin Sinnott, Evan Walters, Claudia Williams and Evelyn Williams. Just as important have been serious reviews of books, careers and exhibitions. Since 2012, Wales Arts Review has been a useful addition to the long-term contribution made by Planet in reviewing art. Publicity may be oxygen but intelligent criticism is far more vital to the culture.

It doesn’t seem so long ago that books about Welsh art or artists were seriously scarce. That started changing in the 1990s but art publishing has burgeoned in this decade. Peter Lord’s new art history of Wales The Tradition provided a beautifully illustrated survey of art since the Reformation. The Buildings of Wales series filled the last gaps in its national coverage, and the Royal Society of Architects in Wales opened a series on Welsh architecture with John Hilling’s grand historical survey. A breathless list of monographs clarified the work and reputations of key Welsh artists, including Charles Burton, John Elwyn, Clive Hicks-Jenkins, Falcon Hildred, David Jones, Heinz Koppel, Sally Moore, Cedric Morris, Peter Prendergast, Edward Pugh, John Selway, Kevin Sinnott, Evan Walters, Claudia Williams and Evelyn Williams. Just as important have been serious reviews of books, careers and exhibitions. Since 2012, Wales Arts Review has been a useful addition to the long-term contribution made by Planet in reviewing art. Publicity may be oxygen but intelligent criticism is far more vital to the culture.

Art UK

As the name says, this isn’t a resource for Wales alone, but what a wonderful resource it is. Art UK was launched in 2016 as the successor to the Public Catalogue Foundation and BBC Your Paintings. Its ambition is to make available digitally all publicly owned art, held anywhere from museums and galleries down to town halls and colleges. All Welsh institutions are included. It began with oil paintings as a manageable subset and is currently moving into sculpture. It already covers 230,000 artworks in 3,200 institutions – for example 297 works by Augustus John; 18 by Brenda Chamberlain; 28 by Shani Rhys James. It’s a superb tool for research and an infinitely satisfying resource for browsing items usually out of sight in offices or stores.

Artes Mundi

You can’t contemplate the last decade without Artes Mundi. It’s become a biennial fixture, now entering its ninth iteration. Like the Turner Prize, it sometimes excites, sometimes leaves people cold. It has injected international art and brought international attention to Cardiff but it sometimes feels more like a brief decamping of the global glitterati than something that could only be here. In the early years some attention was paid to Welsh artists – welcome positive discrimination for a country whose artists struggle to get noticed internationally – but more recently it has been hit and miss whether any were included. For me, the stand-out exhibit of the decade was indeed by a Welsh artist: Bedwyr Williams’s glowing video installation of 2017, pin-sharp and Imax-like in scale, of a fantasy future Cadair Idris, its upland emptiness occupied by luxury apartments.

Richard Wilson

If I had to pick just one revelatory single-artist exhibition of the decade in Welsh art it would be the Richard Wilson survey, held at the National Museum in Cardiff and at the Yale Center for British Art in 2014, the latter of which made it possible with generous funding. Wilson is widely seen as the father of British landscape painting, yet he’s hardly a household name. His gentle caresses of place and nature influenced Turner, Constable and many who came after, yet he’s all too easily hidden in the shadow of the great names. His magnificent paintings of the Dee Valley, big enough to walk into, were shipped over the Atlantic for the show. (Perhaps under the Welsh Government’s proposed regime for regional galleries such shows might go to mid and north Wales too.)

Public art

A lot of public sculpture has landed in the last ten years or so. Some of it has been dismal, like the painfully literal representation of Ivor Novello, swivelling in an awkward chair on Cardiff waterfront. But a few works have been inspirational, like Sebastian Boyesen’s monument to the miners who died in the Six Bells disaster, the Guardian in Abertillery of 2010, which is a towering figure of a miner from certain viewpoints yet dissolves into light and air from others. A group of new statues to notable Welsh women will be put up soon. The recognition is good news, but is the fixing of heroes as figurative statues still a relevant response? Who nowadays gives a second glance to all those old generals, aldermen and coal barons on their pedestals?

Photography comes in from the cold

The decade has been a breakthrough for the Cinderella artform of photography, so powerful in our daily lives and yet so overlooked by galleries. The medium has taken a big step up with David Hurn’s magnificent gift to the nation of his own images and swaps with his Magnum peers. As a condition of giving it to the National Museum in Cardiff he cunningly secured a quid pro quo that there be ongoing displays of photography, an arrangement that has produced remarkable exhibitions already, most recently of Bernd and Hill Becher and Martin Parr. In 2015, the National Library acquired the internationally significant archive of the Welsh-born photojournalist Philip Jones Griffiths: over 150,000 images of war and peace. In 2011, Pen’rallt Gallery and Bookshop opened as a perfectly formed small photography gallery in Machynlleth, since expanded into further premises. This year Ffotogallery relocated to an impressive new home in a former Sunday school in Cathays.

Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape

MOMA Machynlleth is an amazing creation, a maze of galleries infiltrated into the streetscape in a former shop, a house, a chapel and a tannery. Like the bumble bee, no one can work out how it flies, but it’s become ever stronger through three decades, supported by the community, generous benefactors and voluntary effort. In 2016, MOMA put on its most ambitious ever exhibition, which certainly became a highlight of the decade for me as guest curator. It formed a tour through three galleries to explore the critical place of Wales in the history of layered, interpretive responses to landscape. We showed three periods in three galleries with loans from private and public collections. In the Romantic era itself, Wales was a crucial inspiration for Turner, Sandby, Cotman and Thomas Jones. In the mid-twentieth century it was fundamental to the neo-romantic vision of Sutherland and Piper and produced distinctive artists of its own such as Ceri Richards and Ernest Zobole. Contemporary Welsh artists continue to bring a multi-layered concern for landscape and environment, including Helen Sear, Eleri Mills, Dick Chappell and Tim Davies. The exhibition was the gallery’s best-attended to date.

Deaths and Entrances

During the decade we lost a lot of artists, some great, some quietly committed and one or two noted only for their very notoriety. You decide which is which … Joan Baker (1922-2017), Roger Cecil (1942-2015), Maurice Cockrill (1936-2013), Michael Edmonds (1926-2014), Eugene Fisk (1938-2018), Valerie Ganz (1936-2015), John Knapp-Fisher (1931-2015), George Little (1927-2017), Gwilym Prichard (1931-2015), Osi Rhys-Osmond (1943-2015), Wilf Roberts (1941-2016), John Selway (1938-2017), John Uzzell-Edwards (1934-2014), Andrew Vicari (1932-2016), Islwyn Watkins (1938-2018) and Evelyn Williams (1929-2012). They’ve all gone but, to end this review of the decade, here are a few artists who became visible during the same period: Jonathan Anderson, Alexander Duncan, Meirion Ginsberg, Dalit Leon, Dan Rees, Philippa Robbins and Daniel Trivedy – something to look out for with your 2020s vision.

You might also like…

The Martin Tinney Gallery in Cardiff is celebrating its first 25 years with a pair of exhibitions in April and May 2017 which showcase some of the outstanding modern and contemporary art of Wales. Peter Wakelin explores the gallery’s significance in helping to expand the possibilities for Welsh visual art.

Peter Wakelin is a writer and curator. He was formerly Secretary of the Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Wales and Director of Collections & Research at National Museum Wales.