November 7th marks the centenary of the birth of Albert Camus (1913-1960), one of the great European thinkers and writers of the twentieth century. Here, Wales Arts Review co-founder Dylan Moore remembers his own first encounter with the writer and celebrates the enduring legacy of Albert Camus.

The memory of one’s first encounter with some books – and some writers – are so vivid as to seem, in retrospect, almost as if you had lived them yourself. The physical experience of reading – the specific time and place, the atmosphere, the tactile object of the volume itself – becomes inseparable from the events of the novel, say, or the subject of the essays. This feeling is typical of one’s early encounters with great literature. At this point, when teaching sixteen to eighteen-year-olds, I usually quote Italo Calvino. The Italian’s masterful treatment of the question Why Read the Classics? contains the idea that ‘Youth is endowed with unique flavour and significance.’ Our early reading experiences shape us in much the same way that early life experiences nurture, and to some extent hardwire, our personalities. I would go further than Calvino. Some writers, encountered at just the right moment, end up as part not only of our literary psyche but as an imprint on our very soul. So it was for me with Albert Camus.

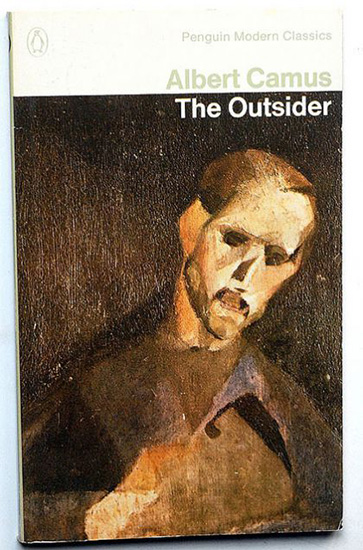

The first of my many encounters with Camus’ classic The Outsider (a book I must admit I have now gone some years without re-reading) is one I recall with an uncommon level of detail and clarity. It seems looking back that aged seventeen I devoured the short existentialist parable in a heightened state of being and understanding. It was the slim silver-grey spined Penguin Modern Classics edition that had found its way onto my father’s bookshelves, like so much of my reading matter in those formative years, via an elderly neighbour who had thinned out the vast and hugely impressive library of her late husband with a characteristic show of generosity to my family. Here, of a sudden, just at the point that I had started reading seriously, was a ready-made pipeline of challenging and judiciously selected material. Joyce, Kafka, Conrad, Thomas Mann, Henry James, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Orwell, Koestler – and Camus.

I remember distinctly the feeling of discovering the classics. Reading the blurbs, whole worlds seemed – and turned out to be, truly – contained within these pre-loved paperbacks. I can still remember the mystery of the quote from Sartre on the back of his compatriot’s novel. ‘I would call his pessimism solar if you remember how much black there is in the sun.’ Devouring the book in one sitting of total absorption, each of its two parts made equally lasting, but very different, impressions on me. Both have had a profound and enduring influence on my life and worldview. Books could do this, I discovered.

by Albert Camus

Penguin Classics

Part One is sensual. Camus’ prose, played out in the first-person voice of Mersault – the infamous ‘outsider’ of the title – is characterised by descriptions that simultaneously undermine the idea of life having any extrinsic meaning whilst paradoxically infusing every aspect of existence with a strange, ‘absurd’ sense of beauty. Here we witness Mersault frying eggs, swimming, sleeping with his girlfriend but refusing to commit to engagement. Despite the character’s infamous emotional detachment from the world, here – oddly, powerfully – is a consciousness with which the reader can identify.

Maybe Camus’ perennial appeal, especially among the young, stems from this core ability to connect with our disconnect, to find and explore the places in our hearts of darkness which most of the time we like to pretend don’t exist. The first-person narration of Mersault installs a voice in the echo chamber of our minds that resonates in the deepest places of our soul. Despite that he introduces himself by saying he can’t remember whether his mother died yesterday or today, that he doesn’t feel the need to take another day off work after the funeral, that he continues as normal, takes his girlfriend to the cinema, we do not condemn him. Society condemns but the reader doesn’t; at least this reader didn’t. Perhaps it is his absolute honesty that appeals, Mersault’s absolute refusal to resort to the million miniscule hypocrisies by which the rest of us get by.

This, of course, becomes the whole point of Part Two, where our man is put on trial. He refuses to cooperate, to play the game that society wants him to play. He becomes, in the title of the long essay that was Camus’ philosophical companion piece to the 1947 novel, L’homme Revolte – The Rebel (1951). And then he kills a man.

This should, by rights, change everything; and, of course it does – but not necessarily in the way we think it would. The meaningless killing of the Arab on the beach (which has since become inextricable from that early Cure single), the details leading up to which are a deliberately forgettable series of petty intrigues, take the story onto a different philosophical plane in precisely the manner Camus intended. Quite apart from anything else, the book’s mitered structure is remarkable. Suddenly Mersault is elevated from a character through whom we can observe the absurdity, but also sensual beauty, of life, to a character whom Conor Cruise O’Brien called ‘the only Christ-figure we deserve’. This was another extraneous quotation that became indelibly printed on my brain.

here – oddly, powerfully – is a consciousness with which the reader can identify

In Part Two the novel is a trial. We are forced into making a decision, taking a side. Are we rooting for a society perplexed by a seeming unthinking murder carried out by a man who – and this is made to appear the most shocking aspect – did not cry at his mother’s funeral. Or are we rooting for a murderer?

By the time Mersault is condemned and Camus has him in a cell awaiting execution, we are actively cheering him on. His refusal of the priest is an act of heroism. Mersault exposes societal hypocrisy by sticking dogmatically to his (non) principles throughout. I think right there in that lonely cell with Mersault was the precise moment I lost the faith in God it has taken me sixteen years to recover. The experience was that profound. Reading Camus was like a religious conversion in reverse. I had been brought up Christian; Camus’ ‘solar pessimism’ turned my worldview on its head. Even now, having had my belief rekindled, I am no less grateful to the writer who first made me doubt.

As I read more from and about Camus, it is unsurprising that he assumed this position. The Outsider led to more purely philosophical works like The Rebel and The Myth of Sisyphus. In these long essays, Camus revealed himself as a writer of deep conscience, sharing Mersault’s disdain for hypocrisy. I loved discovering that the writer had apparently written himself into The Outsider’s courtroom scene, in the form of a cameo appearance. Camus had for a time worked as a young court reporter, reveling in the opportunity to expose corruption and support the defendant whenever the situation required it. Mersault has the ‘peculiar impression of being watched by myself’ and indeed the Camus figure, in his blue flannel suit, puts down his pen and stares directly at the character, even as the other journalists busily take notes.

What I recognised in Camus, staring at the writer through the voice of his creation, was a man of faith. As I went on to discover The Plague – an allegory of the Nazi occupation of France – and The Fall – an atmospheric and intriguing series of dramatic monologues that revived the second person narration of Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground, forming the model for Mohsin Hamid’s recent bestseller The Reluctant Fundamentalist – I learned that Camus was a writer I could trust, to be absolutely unflinching in his looking at his own age, an epoch in which millions were slaughtered and enslaved. The Fall particularly (La Chute in French) was like nothing I had read before, or, in fact, since; Camus’ command of both philosophical argument and literary inventiveness puts him on a rare plane of writer-thinkers able to both construct a coherent yet complex theory of existence and communicate with a wide audience. No wonder he is sometimes regarded as the first intellectual rock star!

Tragically, Camus had the rock star death to match his celebrity. His untimely death in a car crash at the age of just 46 left the world bereft of a major commentator who would surely have played a role in shaping the new philosophical environment which was to emerge in the decade after his death and beyond. In the 1960s ‘rock star’ French thinkers played a major role in the development of Western thought, not just Camus’ sometime-friend, sometime-adversary Jean-Paul Sartre, but a whole new generation. Names like Lyotard, Levi-Strauss, Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, Lacan, Baudrillard and Barthes seem to belong to a totally different era. Theirs was an age of smartness, irony and self-reflexivity; their ability to underpin soundbite phraseology chimed with the heightened times of 1968, when, for a brief period, academia was cool. Their complicated sounding theories of theory – postmodernism, poststructuralism, post-everything-ism – ensured that we lived in a perpetual present. After having read Camus at 17, it was these later French theorists that informed my studies at university.

But looking back now, from a time when postmodernism seems finally to have eaten itself, it is highly doubtful that any of those thinkers will have their own centenaries remembered or marked in quite the same way as Camus. The difference is that, where that later generation was often willfully obscurantist, prioritizing intellectual trickery over engagement with the world itself, Camus pressed his face up against the glass. He was personally involved in the French Resistance cell Combat, whose newspaper he edited; although a man of the left, he rejected communism, causing his famous rift with Sartre; he worked for UNESCO in the 1950s, resigning in protest at the UN’s admittance of Spain under Franco; and he famously faced a moral dilemma during the Algerian War, identifying with pied-noirs like his own parents but ultimately supporting the actions of the French government. His forty-six years encompassed two world wars and the end of the colonial age. The 1957 Nobel Prize for Literature committee had it right when making the award to the second-youngest laureate in history, when they identified Camus’ ‘clear-sighted earnestness’ that ‘illuminate the problems of the human conscience in our times’.

The one hundredth anniversary of his birth gives a great excuse to dig out those paperbacks.