Peter Wakelin reviews The Art of Music, a new history by Peter Lord and Rhian Davies of where Welsh music and visual culture overlap.

If you grew up in the age of the music video, the album cover and the advert-with-a-jingle you know that visual imagery and music build brands. This book applies the ‘branding’ notion to an earlier period and argues that art and music together created a national brand for Wales. At its heart is the widespread conception – whatever it’s reality might be – that we are ‘a musical nation’, a ‘land of song’.

I don’t know how Peter Lord does it – producing huge volumes in quick succession, with this one following close on The Tradition and several other books. On this occasion he has a co-creator, the music historian Rhian Davies. Together, they aim to cut across the silos of historical disciplines to show how visual and musical culture have interacted in daily life. In some 300 pages and as many images, they present a vast quantity of information. Much of the content is little known and many of the images were new to me. Thanks to the support of several funders, Parthian have published a big book to high production values for £40.

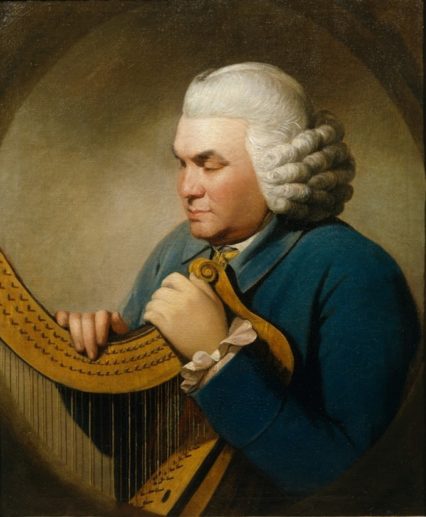

The examination begins with the Medieval and Early Modern bard and the appreciation of music among the gentry. Harpers in particular became revered and frequently depicted (if you want pictures of harps and harpers, they are here in multitudes). None was more famous than the blind John Parry, who was painted with skill and feeling (and remarkably often) by his son William. As the harper for Sir Watkin Williams Wynn, Parry performed for high society in Wales and London and collected traditional music in British Harmony, Being a Collection of Antient Welsh Airs.

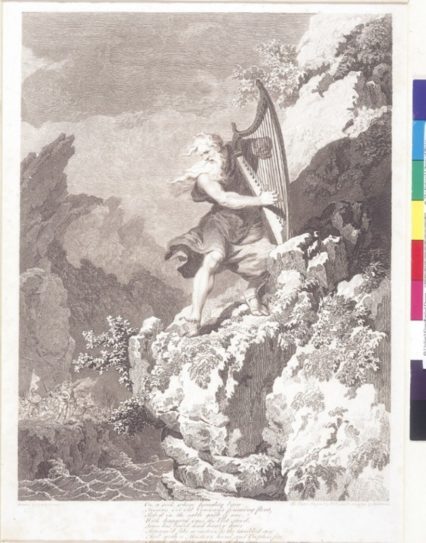

If Parry’s fame helped to kindle enthusiasm for the bardic tradition, it burst into flames in the heat of the Romantic movement. Thomas Gray’s poem The Bard of 1757 was visually reprised for decades by artists such as Thomas Jones, Henry Fuseli and Philippe de Loutherbourg, whose print of the fatal Celt was distributed widely. Suddenly, ancient, bearded bards personified Welshness and expression turned to cliché as artists sought to satisfy the growing market of the curious travellers on the ‘Welsh tour’. Music, too, was debased for visitors: Felix Mendelssohn despaired at Llangollen in 1829 that the barrage of ‘so-called folk-melodies’ played in the hotels was such ‘vulgar, fake stuff’ that ‘it’s even given me a toothache.’ And yet, as the authors say: ‘The fusion of bardic myth and observed if vestigial reality had firmly established the national brand in the mind of outsiders.’

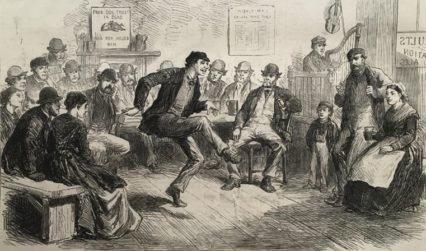

This process of debasement begs a question about the visual culture encountered in the book: how far did it represent people’s experience of music and how far was it a commodity with a different purpose? Much of it was ephemera such as postcards, kitsch souvenirs and commercial advertising as opposed to either illustration of record or great art seeking after its own truth. Among the most valuable of the observational recorders are the reporter-artists of the Illustrated London News in the late nineteenth century. They were sent frequently to capture big events, such as the mass gatherings of harpists at eisteddfodau or great choral occasions and, very rarely, they recorded the culture of the urban working classes, as in a drawing of a step dancer and a harper-come-fiddler entertaining people in a Merthyr Tydfil tavern. Methodist leaders disapproved of such secular music and associated the harp with licentious singing and dancing, so much that for a time religious fervour caused the country’s reputation as a land of song to fade.

Its rescue came in the form of both the National Eisteddfod and the choral movement in the late nineteenth century, which raised the association of Wales with music to a crescendo. Most music, as ever, was inspired not by themes of national identity but worship, joy and sadness, love and loss, and the great European composers were frequently performed. However, a few musical expressions became associated with national pride, most significantly when the song Glan Rhondda evolved through popular affection into the anthem Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau. At the same time in commonplace visual imagery the dominant trope became a feminine persona in invented national costume with harp and tall black hat: ‘Jenny Jones assumed her place as a mythic embodiment of the demure Welsh maiden who would promote the national brand for the remainder of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.’

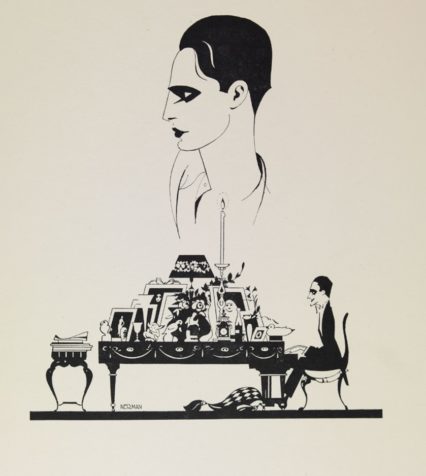

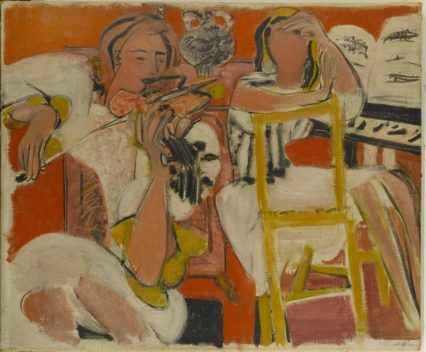

The book’s focus widens in a final coda that picks a few examples from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These have more to offer on the confluence of music and visual imagery than they do on national branding. The worldwide fame of Ivor Novello as writer and performer was accompanied by score covers, films, posters, photographs and caricatures of ‘Britain’s most beautiful man’, but it seldom touched in any way on Welshness. Ceri Richards makes an appearance as the first painter who sought to parallel the experience of music in his own medium – in paintings about home music-making and perhaps most originally in his series inspired by Debussy’s La cathédrale engloutie with its sonorous depths and fluid forms.

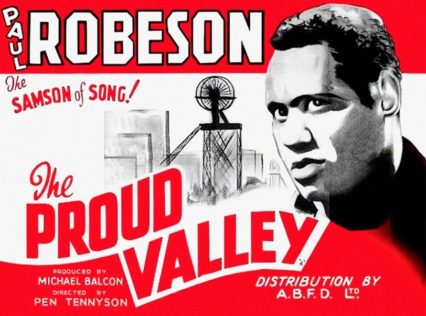

Ironically, the visual culture that most firmly established ‘the land of song’ in global imaginations in the twentieth century was a series of films that were largely caricatures by outsiders, not home-grown depictions. They featured south Wales miners singing through their troubles, elevated in The Proud Valley by the magnificent Paul Robeson, and were spectacularly successful. How Green Was My Valley, filmed by John Ford in the USA, won five Oscars.

The Art of Music is a dense text, filled with painstakingly collected evidence: on harpists, song publishers, eisteddfod-goers and gentry enthusiasts, lyricists and composers, postcard artists and popular printmakers, most of them known now only to specialists. As such it is an exercise in recovery of cultural memory. Perhaps a companion volume one day will tackle the post-devolution era, when ‘branding’ is an explicit discipline and Welsh identity is amplified deliberatively in sound and vision by the likes of Cool-Cymru bands, the Welsh National Opera or the televisual music of Karl Jenkins.

The Art of Music: Branding the Welsh Nation is published by Parthian and is available now.