The ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ / ‘Bywyd Richard Burton’ exhibition is now reopened at the National Museum Wales and Wales Arts Review is publishing a series of essays to run concurrently with the exhibition, curated by Daniel G. Williams, director of the Richard Burton Centre at Swansea University. Each essay will discuss a specific Burton film; this week, Alexia Bowler considers Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? .

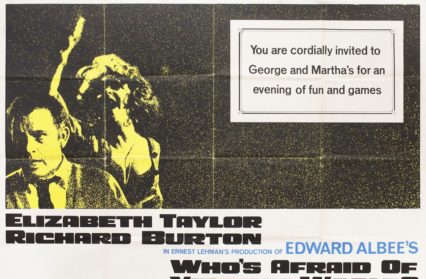

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), an instant classic and the fourth of the eleven films Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor made together, remains memorable in the annals of film history for several reasons. Known for its ‘scabrous language’, the adaptation of Edward Albee’s play was filmed in black and white in an era moving towards colour and was the first film to be nominated for an Oscar in each of its eligible categories

Retaining the three-act structure of Albee’s play (‘Fun and Games’, ‘Walpurgisnacht’ and ‘The Exorcism’), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) centres on one night in the turbulent marriage of history professor George and Martha, the daughter of the president of the New England college at which George works. Returning late from a faculty soirée, Martha tells an irritated George that new faculty member Nick, and his wife Honey, are coming over for drinks. As the four party through the night, Martha and George engage in a vicious battle of wits, drawing the smug Nick and mousey Honey into their verbal ‘Fun and Games’ with devastating consequences. The evening deteriorates as Martha reveals her disgust and disappointment at George’s failure to advance his career, despite the advantage of being married to the college president’s daughter. She flirts openly with Nick (before later attempting to bed him), while George attacks Martha and the emotionally distant father she idolises with increasing verbal ferocity.

Fuelled by alcohol, the awkward small talk and pointed innuendos take a hostile turn when Honey asks about George and Martha’s son, whom we later discover is a fiction used by the couple as a panacea for their troubled marriage. Having broken the ground rules of their private game by sharing it with others, the couple engage in an emotional and exhausting fight to the finish. George, brutally, destroys their dysfunctional illusion by ‘killing off’ their son in his final narrative of the evening. Left with the bones of a marriage as dawn approaches, the film ends with Martha and George contemplating what their future holds.

The film opened in 1966 to rave reviews, with the trade publication Variety calling it a ‘shattering and indelible’ drama and describing Martha and George’s marriage as ‘a magnificent wreck, a hulk that drifts like the Flying Dutchman, a menace to navigation and travellers on the uncertain seas.’ Cecil Wilson referred to Burton’s ‘towering performance’ based on a strong understanding of the ‘razor-tongued, stick-in-the-mud history professor’ and a masterful grasp over the evening’s events. Biographer Paul Ferris identifies Woolf as ‘the one picture of quality’ that Burton and Taylor made together.

Burton’s diaries reveal that he convinced Taylor to go for the part, suggesting that – although she was too young and ‘not enough of a harridan’ – it could be her ‘Hamlet’. If Burton was convinced that Taylor could play the role of Martha he was less convinced of his own appropriateness as Albee’s George. Paul Ferris notes that Burton believed that he was ‘totally unlike Albee’s lean and haunted man’, but felt that it might work to play George in ‘a certain way […] as a sort of decaying, seedy, gone-to-fat, almost obese intellectual.’ While Burton as ‘obese intellectual’ did not receive the Oscar that year, he did secure a best actor BAFTA and the admiration of reviewers such as Stanley Kauffmann who noted in the New York Times that Burton was ‘utterly convincing as a man with a great lake of nausea in him, on which he sails with regret and compulsive amusement’. Despite his own misgivings, Burton was later to list Woolf as one of the few films in which he appeared with Taylor that he could bear watching.

The casting of Woolf, however, was not straightforward. According to Ed Sikov, Bette Davis and James Mason were pencilled in to play the toxic duo. When Burton and Taylor were announced, Albee feared that his play would be undermined by its connection with these superstars and their notoriously tempestuous marriage. Albee commented to Sikov: ‘I think with Mason and Davis you would have had a less flashy and ultimately, I think, a deeper film.’ Yet, the question over whether art is imitating life or vice versa gives the film a certain frisson and Burton, in his diaries, notes that while dining with Albee in Rome in 1966, the playwright was ‘very flattering, especially to E!, about V. Woolf.’

One of the ways in which the film was not an imitation of life was in its transformation of the thirty-three-year-old Taylor into the ‘frowzy’ Martha, a woman in her early fifties. The decision not to film in colour was crucial in this respect, for director Mike Nichols believed – against the wishes of studio boss Jack Warner – that the heavy makeup necessary for that transformation would be too apparent in a colour film. Furthermore, as an admirer of European directors such as Fellini, Truffaut, and Godard, Nichols – following the precedent of the American social issue dramas of Stanley Kramer – felt the intense and claustrophobic nature of Albee’s tragicomedy demanded a realism best captured in black and white; this was no Cleopatra (1963).

The desire to film in black and white was not the only clash that Nichols would have with the studio bosses. One of the major problems in adapting Albee’s play was its language, as well as its troubling portrayal of middle-class marriage at a time of enormous social change in 1960s America. At the centre of this problem was the Hays Production Code. Established by powerful lobby groups in the 1920s as a reaction to perceived immorality in film (and in the private lives of those in the industry), the Code catered to powerful conservative influences concerned with public decency. Jack Warner’s new project caused consternation. The National Catholic Office of Motion Pictures (NCOMP, the renamed Legion of Decency) issued a report warning that while they would wait to see the film, they may have to give it a ‘Condemned’ rating. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) cautioned that if the studio didn’t sanitise the script, the film would not get a Production Seal. As the trade association which ensured industry viability, and tasked with providing moral guidelines for content, they could not be ignored. Nervous of losing the industry’s Code Seal (meaning art house distribution and less box office, or withdrawal from the MPAA), Warner attempted to sanitise the language. According to Ferris, Warner produced a list of words to be eliminated, including thirteen goddamns, twelve variations on Christ and Jesus, including Jesus H. Christ, three bastards, seven buggers, four screws and screwing, four sons of bitches and SOBs, two scrotums and a right ball, together with such phrases as “must have made it in the sack” and “on the living room rug”.

However, by the 1960s audience taste was changing, making the Code seem out of date and Nichols insisted on retaining Albee’s dialogue in its entirety on aesthetic grounds. Even so, Warner executives believed that they had ‘a $7.5 million dirty movie on our hands’ upon first seeing the film. Ultimately, Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf was awarded a rating of A-IV (‘Morally objectionable for adults, with reservations’) by NCOMP, while the MPAA reluctantly gave the film a ‘Code Seal’ on appeal. The film was released with the label ‘For adults only’ and theatres were made to sign contracts stating they would not admit minors without an accompanying adult. This curious diktat, which no doubt heightened its appeal, can be seen on the film’s poster on display in the Becoming Richard Burton Exhibition. Thus, while it would be incorrect to suggest that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? singlehandedly destroyed Hollywood’s forty-year-old Production Code, it contributed the replacement of the Code by a ratings system in 1968.

This is appropriate, as part of Albee’s purpose was to challenge the moral values and myths underpinning American society. Woolf is very much a work of its time in this respect, offering a domestic allegory of a nation riven by tensions as manifested in the escalation of the Vietnam War and resistance to it, in the countercultue and the civil rights movement. Indeed, the title, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? used by Martha to taunt George at the start of the film, challenges cultural hierarchies by alluding simultaneously to the high modernist English novelist and to the song ‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?’ in Disney’s animated short Three Little Pigs (1933). Woolf alludes to literary academicism and American Anglophilia, while the cartoon evokes the idea of ‘blowing the house down’ – which is exactly what happens during the 131-minute-long film.

While the couple’s private fiction of a non-existent son initially sustains them, it also blurs the line between reality and illusion. Eventually the illusory child – an American dream – becomes a sullied mythic space into which they pour all their dissatisfactions. The final third of the film (‘The Exorcism’) enacts a purgation in which they face the ‘death’ of their fictional offspring. In the approaching dawn light, after the departure of Nick and Honey, Martha and George are returned to a private space in which they reflect on the night’s reckoning. They face the reality of their marriage in the cold light of day, bereft of comforting illusions. The film ends with George and Martha, Richard and Elizabeth, inhabiting a monochrome America devoid of its myths of innocence.

My thanks to Katrina Legg, of the Richard Burton Archives, Swansea University.

Alexia. L. Bowler is a senior lecturer in the School of Culture and Communication.