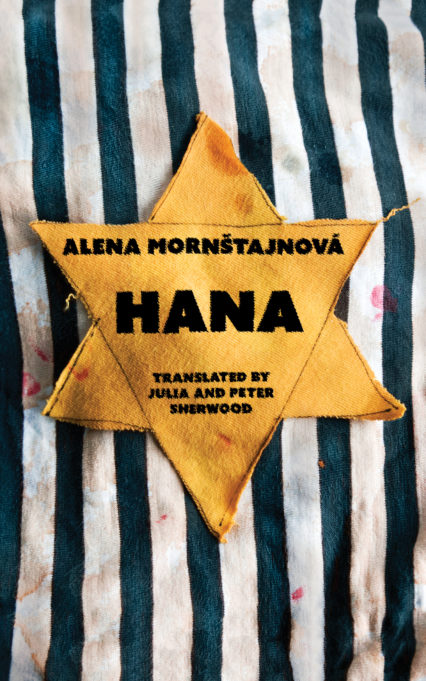

Gemma Pearson reviews Hana by Alena Mornštajnová, an award-winning novel set in a Czech town during the aftermath of the Holocaust which has recently been translated into English.

“Had I been sent to the right I would have died instantly and wouldn’t have had to die minute after minute, hour after hour, and day after day.”

In 1954 in the small Czech town of Meziříčí, nine-year-old Mira senses “evil […] lurking deep in the town’s underbelly”. When a typhoid outbreak decimates Meziříčí’s population, claiming the lives of Mira’s parents and siblings and leaving her orphaned, she is forced to live with her reclusive Aunt Hana. But the quiet, creeping evil that Mira was so attuned to runs even deeper than this. A monstrous period in European history – the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party, the Nuremberg Laws, and the Holocaust – flows through Meziříčí’s veins, infecting the town with anti-Semitic prejudice and fear. Told in three parts and spanning two distinct timelines, readers are transported between 1940s and 1950s Meziříčí, a ghetto in Terezín, and Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. As Mira uncovers the truth about her familial history, the reasons for her aunt’s behaviour, her undernourished appearance and the tattoo on her wrist are revealed. Translated from the original Czech by Julia and Peter Sherwood, Hana is a powerful novel about unimaginable suffering and the epitome of human evil.

Having already won the 2018 Czech Book Award and been translated into over a dozen languages, Hana is set for further success in the Anglophone world and, perhaps, just at the right time. In a Wales Arts Review interview to celebrate Women in Translation Month, translator Julia Sherwood points out:

Now that our insularity is likely to increase due to Brexit, it is even more important to bring translated literature to readers in the UK. And as the pandemic has lately made international travel more difficult, literature in translation offers a way of transporting us to other countries, at least in our imagination.

At a time when conversations about cross-channel migrants, systemic racism, and modern-day mass internment camps saturate the media, increasing the diversity of our literary landscape feels more vital than ever because, if we can face history head on, perhaps we are less doomed to repeat it.

Despite some lengthy sentences that sometimes detract from the overall impact of the narrative, Mornštajnová’s prose is generally clear and measured. She shifts smoothly between timelines, voices, and perspectives, rendering Hana a moving and absorbing story about intergenerational suffering.

The first nine chapters focus on Mira, who is filled with curiosity about her family’s past. Little does she know that for her surviving relatives, the past is often too painful to talk about. Later, in the second section of the novel, readers are thrust back in time to occupied Europe when the Nazi’s de-humanising, anti-Jewish measures were first coming into force. Mornštajnová’s attention to historical detail is evident in the inclusion of real events such as Kristallnacht, the introduction of the Yellow Star, and the widespread boycott of Jewish businesses. In the final chapters, readers witness how many Jewish survivors – having suffered unimaginable psychological trauma – struggled to reintegrate into society after the war.

Mornštajnová’s preoccupation with the unspeakable nature of the Holocaust is perhaps the most striking aspect of novel; she has a distinct talent for giving power to what is not there and not said. Of course, there are many harrowing depictions of suffering, starvation, abuse, disease, and death in Hana but Mornštajnová avoids extreme, “torture-porn” style scenes, instead relying on omission to express Hana’s trauma: “Aunt Hana hardly ever spoke, she just stared. In that funny way of hers. As if she were looking but didn’t see. As if she’d gone away and left her body on the chair.” Reflecting the unspeakable nature of the Holocaust itself, Mornštajnová uses Hana’s silence as a discursive tool that is both powerful and revealing.

For many, the atrocities of the Holocaust are a mere two or three generations away. There is, as a result, a difficult moral quandary when it comes to reading Holocaust literature. Theodor Adorno famously said: “To write a poem after Auschwitz would be barbaric”. For how can the horrors of the lived experience ever be accurately or adequately conveyed in an artistic rendering when, by its very nature, such violence is so indescribable, so unimaginably evil? Nevertheless, in reading literature, we cultivate empathy for and identification with the characters on the page, their suffering becomes new and agonizingly fresh, and their stories become immediate, personal, and intimate. Thus, if history teaches us what happened, literature teaches us how it felt. Demonstrating how pain and trauma seep from one generation to the next, Hana is an important and impactful novel that reminds us that no society is ever immune from the plague of complicity.

Hana, written by Alena Mornštajnová and translated by Julia and Peter Sherwood, is due to be released by Parthian on October 1st.

Gemma Pearson is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.