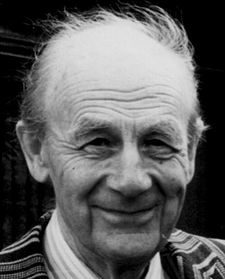

In the centenary of Jonah Jones’ birth, Adam Somerset looks back at the sculptor’s early life in his review of Peter Jones’ book Jonah Jones – An Artist’s Life, which was released by Seren in 2011.

Jonah Jones was born 17th February 1919. His centenary was marked with an exhibition that ran from January to March at Oriel Plas Glyn y Weddw. On the opening weekend the Western Mail magazine carried a feature ‘Celebrating Jonah Jones’ Centenary’. The exhibition featured on Heno on 12th February in which Angharad Mair interviewed Jones’ son Pedr, gallery director Gwyn Jones and sculptor Meic Watts. It featured on Radio Cymru’s Stiwdio on 20th February and a feature by Non Tudur appeared in the 7th February issue of Golwg.

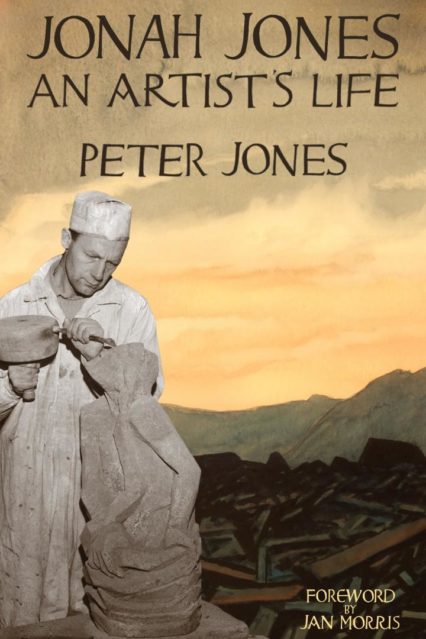

The media coverage was strong. Jonah Jones is also beneficiary of a fine permanent memorial in print. Seren published in 2011 Jonah Jones – An Artist’s Life. The author on the cover is Peter Jones, who is also Pedr Jones, a 30-year-long contributor to Radio Cymru and S4C. The book, a full testament to a full life, opens with an introduction by Jan Morris. The Morris home has not only paintings, books and a slate name-plate of Jonah Jones but also a gravestone-in-waiting. Pedr Jones ends his book with three pages of bibliography and five pages of catalogue. The names of Wales’ twentieth century run through the Jonah Jones legacy: Gwynfor Evans, Saunders Lewis, Lord Morris of Borth-y-Gest, John Cowper Powys, Clough Williams-Ellis.

Richness of detail is the oxygen of good writing and Peter Jones creates it over the course of his father’s life. His parents met during the time of military service just prior to the formation of Israel. Jones was introduced to his future wife Judith by a major in the 1st Royal Ulster Rifles by name of Huw Wheldon. From his camp to the family home on Haifa’s Mount Carmel was a distance of sixty-five miles, a journey undertaken on an army motorbike. Peter Jones captures the atmosphere after the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. A young woman in a Tel Aviv street spits on Jonah Jones. While on a bus a girl tells her friend not to sit “next to a dirty Nazi anti-semite.” Jones is able to reply in the meticulous Hebrew that he has learnt.

The episode is all the more ironic when set aside the most searing experience of Jones’ wartime years. He was among a group of medical staff to enter the newly liberated camp of Bergen-Belsen. It left “an ineradicable mental scar”. A half-century on, in 2002, the effect of the series Band of Brothers on television caused him to weep. “It was so authentic, so exactly what it was like,” he wrote.

Jones had already seen war. In France he was tasked to bury a soldier. The corpse in mid-winter being frozen solid, the grave-diggers were obliged to break the bones. He and his comrades sheltered from attack by mortar and dive bomber. “The terror was still vivid fifty years later,” writes Peter Jones. Jones senior was moved to the south of Holland to see that country’s terrible time of famine. His job was to fumigate the citizen population, infested with lice and scabies, with DDT powder. The crossing of the Rhine Jonah Jones himself later wrote about in a 2000-word essay “The Bloodstone Ring” in 1999.

Peter Jones covers the life before the war service in an economical twelve page first chapter “Child of the Depression: 1919-1939”. Jones’ father, Norman, was a survivor of Gallipoli and the Somme but gassed and wounded in the head at Vimy Ridge. A brother, born in 1920, died at four months, “possibly”, writes Peter Jones, “due to malnutrition during a pit strike.” A sister developed rickets as a result of underfeeding. In Felling, Northumberland water came from a standpipe and the outdoor water closets were cleared once a week by men on a cart and then disinfected with carbolic.

Jonah Jones was aged seven at the time of the General Strike. The strike itself ended in May but the miners stayed out until October. It meant constant hunger alleviated by the daily visit to the soup kitchen. There was a supply of vegetables and rhubarb from an allotment. The boy helped out by visiting the refuse from the earth closets “riddling it for coke-like cinders.” When a dentist in the next century commented on the small size of his teeth the artist’s reply was simple: “I was a child of the Depression”.

Jonah Jones at the outbreak of war opted for Conscientious Objector status and he was directed towards forestry work. In 1943, he enlisted with non-combatant status, but Peter Jones describes the forestry period in Kirkcudbrightshire, Wensleydale and Somerset as crucial. The demanding work built him up physically but he also saw nature close-up and in seasonal detail. He re-read Hardy and Lawrence.

The life of the artist began after release from the army. It was writing that first lured him, digging deep into Felling Library. The result of his research into Tyneside history and culture was “Coaly Tyne”, “remarkable for its scholarship and the thoroughness of research that it reveals.”

The visual arts were ignited by the acquaintanceship with John Petts from his army days. Petts’ curatorship at Llanystumdwy’s Museum prompted the move to Wales. The first home was a half-wrecked cottage, Bron y Foel, a half-mile up a track and first spotted in pouring rain. The work, a six miles cycle ride one way, to Petts’ Caseg Press paid sixteen pounds a month.

Meanwhile, the impact of Belsen went beyond the psychological. Chronic tuberculosis, most likely contracted at the camp, rendered him an invalid for a year. The description of the treatment, a cause of shudder to read, is an echo of that which Derek Lindsay put into his classic novel The Rack. The artificial pneumothorax treatment required a needle inserted through the ribs without anaesthetic. After this appalling interval he renewed the artistic career, becoming in 1953 a member of the Guild of Memorial Craftsmen.

Peter Jones slips in that his subject never acquired great reward. The time taken off was small. Over a ten year period he made five trips abroad. He made appearances in television films, did book designs, wrote occasional poetry. He maintained an active presence in art education, committee membership and evaluations. Membership of the Summerson Council on art education was time-consuming. Other members were salaried. As common the attendance allowance for the actual artist hardly compensated for the time lost and the earnings foregone. A letter in March 1987 recorded a return from Wimbledon’s College. “The new principle [sic] is an accountant, I think, anyhow not remotely linked to art and design. And it’s a bloody good school so I blew my top.”

Peter Jones’ focus is on the life and the making of the work rather than art criticism.

He notes the influence of the later Ernst Barlach in the use of dramatic, stylised gesture. Jones’ move to a position of centrality in the public art of Wales came with the portrait of OM Edwards in Llanuwchllyn. The volume of commissions necessitated a larger space and he took the offer of the ground floor of Tremadog’s market hall, owned by Clough Williams-Ellis. An accompanying photograph shows the sculptor mid-work next to a fellow-tenant, one of a group of Breton onion-sellers.

In the late sixties the church commissions reached their peak at Denbigh and Morfa Nefyn. The wall sculpture at the Mold Law Courts, in blue slate and white marble, was a stylistic innovation. His third and largest wall sculpture was for the foyer of the North Wales Police. It ended its life, notes Peter Jones, in 2002 in a skip, a victim of refurbishment.

Stylistically the work evolved in the seventies, sawing and sanding taking the place of carving, landscape and the Mabinogi featuring over religious themes. Corris Man in 1974 interpolated a line of forms in slate with white marble. In 1981 he took up a year’s fellowship at Gregynog, lyrically recorded in his journal. A new departure was the series of watercolours inspired by the surroundings. 1990 saw a retrospective exhibition at the Mostyn Gallery. Illness in the summer of 2004 went undiagnosed until revealed in mid-November as a brain tumour. Peter Jones records a witness to the artist as on “a sort of plateau of stillness and patience; waiting really.”

Peter Jones recalls many an episode in a rich life. A nice one occurs in 1962 when a teenage son tunes into Top of the Pops. “I give them a month!” says the sculptor as they watch the performance. The song being sung on television is called “Love Me Do”.

Jan Morris wrote that “he always seemed to stand apart, on the edge, pursuing his own transcendental purposes”. Final words go to Jonah Jones’ obituarist, Meic Stephens: “For him, as for the Benedictines, laborare est orare, whether biblical or demotic, was the main source of his inspiration. The Trajan alphabet and the graffiti on the walls of the Roman catacombs were both, in his mind, proof that in the human psyche there is a profound desire to make one’s mark as a permanent record in a fleeting world, and he believed that the artist, as quintessential man, was best equipped to do what he called ‘leaving my scratch’.”

A collection of Adam Somerset’s essays Between the Boundaries, is available now from Parthian.