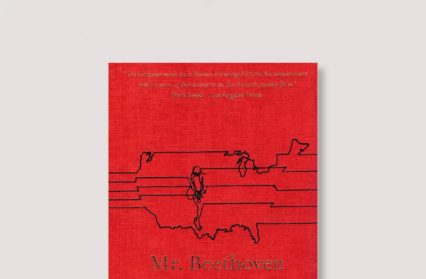

Ludwig van Beethoven died in March 1827, but what would his future have held had he lived on? Nathan Munday reviews Mr Beethoven by Paul Griffiths, a novel which explores such possibilities through a fictional continuation of the prolific composer’s life.

Overture

A few years ago, I was sitting in a chilly Troutmark Books selling paperbacks in the run-up to Christmas. It was the pre-covid era — confident and chaotic — and Wham!, Wizzard and all those other Christmas songs contributed to the nostalgia of the echoing arcade. As the Reachers and Potters sold, something remarkable happened: Jacques Loussier started playing on the tannoy (some saintly security guard had done a Shawshank Redemption and invaded the monotonous playlist). In that special moment, Bach’s mechanical pieces were transformed, and I learnt that Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring could, and should, have a crashing cymbal at the end. My discovery of Loussier meant that the eternal arpeggio of that old, blue cello book could be interpreted differently…

(Perhaps for the remainder of this review you should listen to some Loussier, Bach, or even some Beethoven in the background.)

Aria

…and then, in one of the longest caesuras in living memory, I read Paul Griffiths’ Mr Beethoven which muses on the role of interpretation in the arts. Published during the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827) — one of the noisiest, and deafest, classical composers — Griffiths cleverly intertwines Beethoven’s recorded words with a fabricated reality in a meticulously layered novel. What could have happened, and what might have been, shows the fragility of that line which exists between fact and fiction.

Duet

The man who gave us the Moonlight Sonata, the duh-duh-duh-duhhh of the Fifth Symphony, and the Ode to Joy is resurrected in the first few pages. Not in Vienna, but on a boat in the middle of the Atlantic. Neither is he that pale, shrunken figure, sitting grumpily on the top of so many middle-class pianos but he is:

“Mr Beethoven!”

A deafer, older composer, snoring away in a boat never boarded, on route to a country he never visited. Rather than dying in 1827, the composer travels to America in 1833 long before the likes of Dvořák, Rachmaninov and Bartók. His New World piece will be the next great oratorio, commissioned by the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston with lyrics written by one ‘Rev Ballou’, a ‘huffing puffing’ Unitarian minister. The subject? Job. King Lear’s ancient doppelgänger, caught in a cosmic interlocution between God and Satan. Never was there a man more concerned with self-interpretation… until Beethoven that is.

Back in the boat, a young boy fails to wake the genius up for dinner. It’s a comical scene, and one which is very familiar to the reviewer whose wife is also hearing-impaired. Finally, with a robust shake, and the abracadabra of “Mr Beethoven!”, this modern Lazarus emerges from his silent tomb:

Yes, the eyes opened and the face came alive. The head turned a little, so that these newly opened eyes might look directly at the face of the one who had summoned them from whatever dream.

Chorus

All of this might have happened if Beethoven had lived longer. A footnote is provided by the narrator — or is it Griffiths the scholar? — in which we discover that Beethoven was once approached via the American embassy in Vienna to write an oratorio in English. But that’s all we get.

Once in Boston, the story takes off. Staying with Harvard’s president, he is soon introduced to the overwhelming panoply of nineteenth-century American society. At times, the crescendo of semi-fictional characters is overwhelming, but I think this was probably the author’s intention. However, we are soon introduced to Thankful, someone far more interesting. No, she’s not a character from Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress but a local girl who teaches the composer a special form of sign language developed in Martha’s Vineyard due to a congenital deafness on the island. She guides him through the unheimlich of New England, the ups and downs of composition, and the final performance of the oratorio:

She is the great composer’s ears, and her hand gestures no more need to be described than would, were the transmission direct, the vibrations of the stereocilia. Let her be. Again, let her be. Let her listen, and form her own judgment.

She becomes ‘his earpiece’, ‘not his mouthpiece’ — an instrumental, filtering figure who veers towards the symbolic. Crucially, she’s the one who assists his friendship with Mrs Hill, another silent female who seems to ‘dwindle into stereotype’. However, the same Mrs Hill subsequently re-writes Ballou’s dull lyrics into better poetry.

Aria #2

Paul Griffiths plays with form and language throughout. When the reader drifts, they are soon re-captivated by the skill and strength of the writing, especially in the author’s use of metafiction. Some chapters blur the line between music and literature. Even the narrator speaks in this rather strange future conditional tense which reminds the reader that all of this is, after all, speculative. Sometimes, I forgot that the book was fictional; surely, that sense is one of the columns of good, historical fiction. Jon Day, in his scholarly review, has already noted how this book is a kind of blueprint for a historical novel that’s yet to be written:

Mr Beethoven is both a novel and an essay on the methods and limits of fiction. Sometimes it reads as notes towards a novel that has yet to be written rather than that novel itself: the score of a performance yet to be heard.

I totally agree with him. Can we really fictionalise history when we know so little? Is there a difference between giving a voice to the Beethovens of the past, and inventing someone completely new? This is complicated further by the fact that Griffiths does use Beethoven’s own words (translated, of course).

Finale

Griffiths comes across as a sceptic. He doesn’t fully adhere to the doctrines of historical fiction and, for this heresy, some of you may not enjoy his work. I, however, followed the travels of Mr Beethoven with enthusiasm and, who knows, maybe one day, I will enjoy a counterfactual performance of Job: An Oratorio.

Mr Beethoven by Paul Griffiths is available now from Henningham Family Press.