Thomas Tyrrell casts a critical eye over the latest young adult novel from Catherine Fisher, The Clockwork Crow.

A deserted station platform. An orphan girl travelling alone to meet her mysterious godparents. A worried stranger, abandoning a mysterious parcel. It’s a classic beginning, thrusting us instantly into the plot, and one that works equally well for a Victorian-Gothic novel or a mystery thriller. One of the pleasures of The Clockwork Crow is that it succeeds in blending both and adding a dash of fantasy for extra spice.

The Newport-born author Catherine Fisher is one of the most famous names in children’s fantasy, the writer of well-received books like The Snow-Walker’s Son and the Incarceron series. Surprisingly, this is the first of her nineteen novels to use a Welsh setting, but she takes to it immediately, using Welsh folklore to excellent effect. We begin with thirteen-year-old Seren Rhys en-route to Plas-y-Fran, one of the vast Victorian manor houses of industrial Wales.

Instead of the warm welcome, she was dreaming of, however, her arrival is a frosty affair, with her godparents absent in London, and the few servants in the house hiding secrets of their own. Left to her own devices, she amuses herself by assembling the contents of the parcel, a mechanical crow driven by clockwork. Once all the gears are in place, she winds the key, only to leap backwards in surprise as the crow comes to life and starts crying out for oil in a grating rusty voice. With her evasive and not wholly trustworthy corvid for a companion, she must unriddle the mysteries of Plas-y-Fran. What has happened to Tomos, the missing child of the house? Why are the staff so afraid to speak of him? Only then can she venture into Plas-y-Fran’s mirror image, an ice palace in the Celtic Otherworld where the Tylwyth Teg imprisons the children they have stolen away.

Plotting is one of the great joys of children’s literature, and Catherine Fisher delivers an enthralling story, as well-weighted and as perfectly balanced as… wait for it… clockwork. The first two-thirds of the book gives the reader all the shivery pleasures of the Gothic novel: a forbidden wing that Seren must never enter, an enigmatic presence in the house that may be spying on her, and a mysterious past tragedy that the stern housekeeper, Mrs Villiers, refuses to speak of. If the individual elements recall Gothic fairy-tales like Bluebeard or Beauty and the Beast, however, the structure is more like a detective novel.

Catherine Fisher has clearly been reading her Sherlock Holmes—and so has Seren Rhys, devouring them on their first publication in the Strand magazine. There are clues aplenty, but also dead ends, red herrings, broken threads: some of the mysteries have mundane explanations, and at other points Seren Rhys’s imagination has led her astray. Introducing an unreliable narrator and the features of a murder mystery to a Gothic novel reinvigorates the old plot elements and gives a fresh satisfaction when the true pattern of events finally emerges. It’s easy to imagine saying, “If you liked this, then you’ll love…” and handing an enthusiastic child a copy of Jane Eyre, The Hound of the Baskervilles or an Agatha Christie.

The final third of the book is set in the beautiful but dangerous Celtic Otherworld, where Tomos is being held, prisoner. The switch between the logic of the Gothic novel and the logic of the fairytale might have unseated a lesser writer, but Fisher remains firmly in control, giving us just as much magic and terror as we could desire, but making sure we understand that actions have consequences, magic has its price, and the Twyth Teg’s own carelessness leads to their final undoing. It’s a difficult task to do anything new with fairies and changelings in the wake of the massive loss of Sir Terry Pratchett, whose The Wee Free Men casts a long shadow over succeeding writers, but the plucky stubborn Seren Rhys stands up well against Pratchett’s witchy-but-practical Tiffany Aching. Fisher’s half-glimpsed Tylwyth Teg are never as fully developed as Pratchett’s commanding Queen of the Elves, but they’re memorable adversaries nonetheless: eldritch rather than glamorous, more frightening than seductive. The Crow itself is a wholly new ingredient, an obstreperous but charming character, useful and versatile but not always reliable, whose company brings out Seren’s bravery and inquisitiveness. As with Holmes and Watson, it’s hard to get enough of their mismatched pairing and occasional squabbling, and the ending wisely leaves the door open for their further adventures.

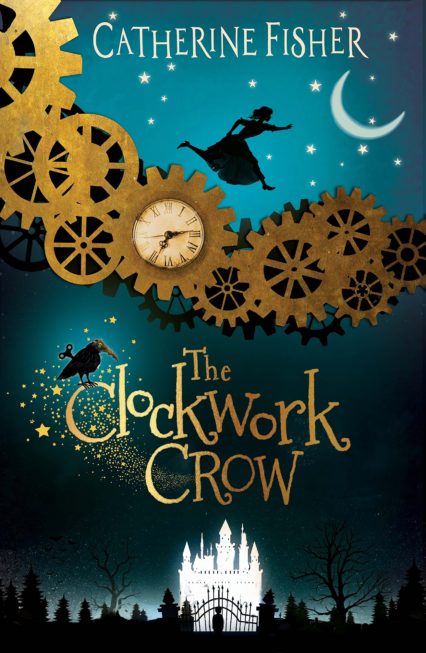

The Clockwork Crow is a wholly satisfying read, a winter armchair book whose storytelling pleasures are multiplied by an awareness of the cold and darkness beyond the window, and the way the fabulous black-and-gold cover gleams in the firelight. Read it over Christmas, and don’t even think of saving it for the Spring.

The Clockwork Crow by Catherine Fisher is available now from Firefly Press.

Thomas Tyrrell is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.