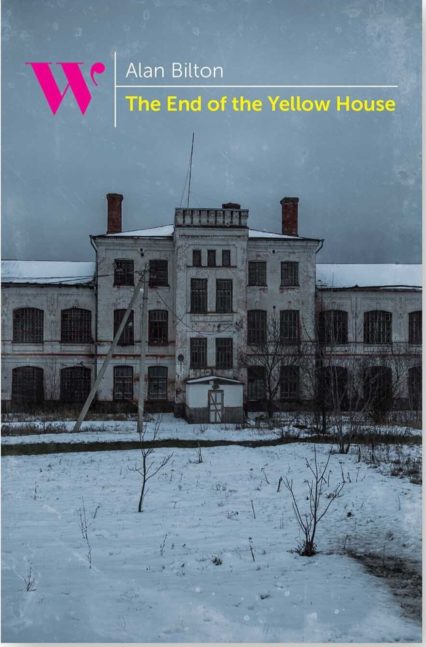

Gareth Smith reviews The End of the Yellow House by Alan Bilton, a novel that blends history, horror and mystery into a narrative about an early twentieth-century Russian sanitorium.

Alan Bilton’s The End of the Yellow House is, aptly, a Russian doll of a novel in which an Agatha Christie-style whodunnit, a gory horror story, an examination of Soviet political history and a meditation on madness contain one another in a carefully crafted whole. Set in 1919, the eponymous Yellow House is a former sanitorium for the wealthy which has deteriorated into a filthy, dangerous and anarchic lunatic asylum. The novel begins with a darkly comic description of a discovered corpse as the mangled body of Superintendent Lepinov is found at the bottom of a well. A sardonic, macabre tone is established which persists throughout and ensures that each character and situation is viewed with both detached mockery and grim fascination.

Lepiniov’s murder causes a power vacuum in the hospital which the remaining doctors struggle to fill, each of whom practices vastly different forms of medicine and display opposing political allegiances. Bilton establishes a convincing collection of possible suspects with numerous skeletons in the closet (or, in one case, monstrous experiments in the basement). This prompts the arrival of a mysterious and flamboyant police officer, Tutyshkin, who gleefully exposes the vulnerabilities of those around him while attracting the suspicious attention of everybody he meets. Bilton plays a cat-and-mouse game with Tutyshkin’s character, toying with our expectations of his ‘true’ identity while continually keeping us in the dark. As in all classic mysteries, the body count begins to rise as the residents of the Yellow House become more frantic and isolated.

These elements alone make for an intriguing mystery, but the novel’s setting allows Bilton to focus on the horrors of medical malpractice. There is much more to fear from the doctors than the patients and invasive, dangerous and lethal treatments are described in painstaking detail. This provides several gory set-pieces throughout the narrative which casually, if effectively, convey the disturbing history of treatment for mental illnesses. The novel veers from an unsettling creepiness to full-blooded horror, reaching its apex in a scene reminiscent of a Universal monster movie. While some residents are allowed to engage in the relaxing Freudian ‘talking cure’, it soon emerges that the severity of treatment is dictated by class – even in the midst of an apparent social revolution.

This engagement with a broader historical context adds another fascinating layer to the narrative. The Yellow House becomes a microcosm of the country, as competing ideologies and unchecked power wreak havoc on the lives of those caught in the crossfire. The characters are trapped inside during a historical moment defined by uncertainty, hopelessness and warring political factions. Individuals quickly become pawns in a political chess match, the course of their lives changed by a situation they can barely comprehend. The novel’s multiple genres are not incidental to this theme but rather an extension of it – post-revolutionary Russia is both a mystery and a horror to those experiencing it.

This fascination with madness is also not merely a by-product of the novel’s setting, but instead instrumental to its examination of a society in chaos. Authority figures engage in behaviour as dangerous, illogical and cruel as those seen to require ‘treatment’, highlighting the precarity of the lines separating them. This is conveyed effectively within the narrative, which makes moments in which characters literally articulate such thoughts seem clunky rather than self-referential. While the novel undeniably exploits the concept of ’madness’ for humour and horror, it is never to the point of outright insensitivity. Rather, it depicts the historical weaponising of insanity as a means of control and an extension of social and political power.

Bilton writes with a clear love for a Russian idiom (they can be found roughly every third paragraph) and an eye for detail which dwells particularly on the vulgar and the scatological. Its plot, on the other hand, winds several narrative strands together with an effective elegance, expertly increasing the tension and pace as the novel drives towards the climax. It is only once The End of the Yellow House concludes that it becomes clear that the narrative was a prolonged exploration of identity and social roles. Whether as suspects or victims, Communists or Monarchists, or merely sane or insane, each character is playing a part foisted upon them by circumstances far beyond their individual control. The various layers that envelop this central preoccupation, however, ensure that the novel is as entertaining as it is thoughtful.

Alan Bilton’s The End of the Yellow House is available now from Watermark Press.

Gareth Smith is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.