Liam Bell takes a deep dive into the concept of Uncanny Environments and through the Cardiff Flooding in February 2020, discusses how the products of climate change affect how we understand the environment and how we arrange psychological and physical senses of place.

This year WWF issued The Living Planet Report 2020 detailing the catastrophic effects of climate change and the damage human exploitation has had on wildlife globally as well as offering solutions to rebuild our relationship with the nonhuman world and respond to climate change. The WWF’s report and others like it are a call to action issued to individuals, governments, and private corporations – the message received is that it is not too late to change, but almost.

The climate crisis is overwhelming from an individual perspective and has a psychological impact. In the interim of two years since the last LPR from the WWF, no substantial changes have been reflected in government policy in the United Kingdom besides conservationist sophistry. Phoebe Weston in The Independent reports that the government in the U.K. has ‘[…] failed on “pretty much every aspect” of protecting wildlife and the environment’. Clearly, not enough is being done to respond to the damage of anthropogenic climate change. The horror of what is happening to the planet is actively repressed, the powerful sense of aversion and denial at witnessing ecological destruction is only a short-term coping mechanism to the wider environmental issues that require urgent action.

The effects of global climate change appear strange and uncanny, the standards of what is normal have shifted to include the extreme, altering the traditional conceptions of the nonhuman world. The effects of climate change that appear in catastrophic weather events undermine human conceptions of space and place in the psychological and physical environment. It might seem inconsequential or anthropocentric to consider human notions of the environment as a factor in the face of devastating wildlife decline, significant loss of life and livelihoods across the globe, however, our responses to place and environment inform our actions and relationships in respect to the nonhuman. How we psychologically order the world around us informs our daily lives and how we respond to other life on the planet.

The recent flooding that occurred in Cardiff (February 2020) demonstrates how a comparatively small event can nevertheless induce an unheimlich reaction. The areas surrounding Cardiff flooded after the banks of the River Taff burst due to the arrival of Storm Dennis. This, naturally, caused concern for property, life and livelihoods but it also challenges our perception of a familiar place. Focusing in on Bute Park, the flood brought the sudden unexpected appearance of a temporary lake in what was a field the day before. Climate change has the potential to alter recognisable sites in short spaces of time. In the human imagination, coming to terms with both spatiality and temporality are parts of being able to dwell in a given environment. The sudden appearance of an unexpected feature in a short space of time accentuates the unheimlich effect of climate change and requires a reconceptualisation for those familiar with the given space. The changes enacted to a known site, such as a park, that is visited regularly and has familiar features underscores the presence of climate change and its effect on the imagination.

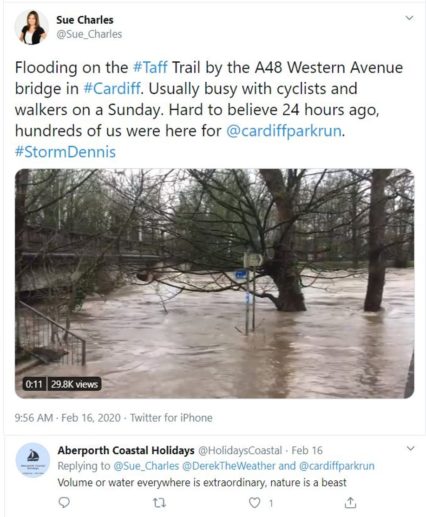

During a climate change event, we experience alarm, confusion, and a disruption to daily life. Below we can see two tweets reacting to the flood in Cardiff demonstrating some potential responses to flooding. The absence of people performing familiar functions is highlighted as usual practices are suspended in the event of flooding and comparative events. The issues with space/time are also present as the impermanence of the environment is met with disbelief. The rate at which a climate event occurs makes reconceptualization difficult – the stark contrast between the recent past and the disruptive present are causes for alarm. The comment underneath the video reflects the same sense of incredulity at the flood while also gesturing towards a sense of alarm or fear of nonhuman “natural forces”. The ecophobic anxiety in regard to ecological disasters presents a barrier to human/nonhuman engagement – they are viewed as the unknown, unpredictable, and ‘[…] hostile forces’.

The process of individual psychological repression, where undesirable thoughts are forced to find a home in the unconscious only to re-emerge later, has parallels with the unheimlich characteristics of climate change. The repression of abject substances, such as waste and toxic pollutants are literally and imaginatively suppressed. In an imaginative sense, we attempt to look away from the mountains of floating trash in the oceans, and keep the thought of emissions away from our consciousness to preserve peace of mind. In a physical sense contaminants and pollutants are repressed in toxic dumps and released into rivers and oceans – they leak into the actively ignored parts of the world and emerge in the form of disasters and the environmental uncanny. Amitav Ghosh, in The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, outlines the emergence of extreme climates that are formed by ignoring and repressing waste materials. Ghosh states that:

we are now in an era that will be defined precisely by events that appear, by our current standards of normality, highly improbable: flash floods, hundred year storms, persistent droughts, spells of unprecedented heat, sudden landslides, raging torrents pouring down from breached glacial lakes and […] freakish tornadoes.

Among the myriad potential psychological states climate change could prompt (e.g. denial, disassociation, anxiety etc.) is to produce an unheimlich version of the nonhuman world we were familiar with. To quote Freud, ‘The better orientated in [their] environment a person is, the less readily they will get the impression of something uncanny in regard to the objects and events in it’. And thus, the speed at which climate change has altered the environment has made orientation to the world a more complex issue that ever anticipated.

For Jentsch, the uncanny arises from the unknown. This definition of the uncanny registers a desire to master the given environment, a notion still present today despite the efforts to dethrone human/nonhuman hierarchies. The sudden appearance of unexpected weather and disasters creates an uncanny effect, as events they appear incongruent with the known environment and contrary to expectations.

Jentsch’s version of the uncanny points towards the need to order the world around the human subject who are themselves oriented by the known environment. As well as being characterised by a lack of order, the uncanny arises from the defensive position humanity assumes and intimately links the uncanny to an ecophobic anxiety concerning the nonhuman, a process accelerated by climate change. The fear of what could be termed “natural forces” (the sea, forests, weather etc.) is still present today – the anxiety and sense of vulnerability in the face of the nonhuman grows as we encounter extreme climates as standard. The products of climate change affect how we understand the environment and how we arrange psychological and physical environments. As previous methods of ordering our environment become obsolete, solid notions of how we view the world are undermined by the unexpected appearances of what was once considered extreme climates. Secure foundations and previously fixed notions become unstable and attempting to affix order to our physical and psychological environments become increasingly challenging as we face large-scale changes to the world.

There are implications for the concepts of the homely / unhomely in the context of environmental studies and climate change when we consider the prefix eco. The root word for eco, as in ecosystem and ecology, is taken from the Ancient Greek word oikos. One definition of oikos describes homes and houses. In effect, the changes to global and local environments affect our responses to the oikos, the ecological home. Climate change, resource depletion, falls in wildlife population, and loss of habitat all serve to make the world physically and psychologically unhomely for both humans and nonhumans. The loss of habitat for nonhuman animals creates a literally unhomely world. This is equally true for humans globally, as the rate of climate change and loss of habitat renders environments unrecognisable and unfamiliar, causing both people and other animals to become dislodged from their homes and thrown into a transient state of out-of-placeness and homelessness as climate migrants.

This is what climate change means practically, the literal loss of a home, the destruction of the ecological oikos. The physical manifestations of climate change and ecological damage such as forest fires, floods, and deforestation change our imaginative concepts of place by instilling a state of impermanence whilst also creating real physical changes. In extreme cases, which are progressively becoming the norm, whole villages/towns/cities/islands are lost and lives are destroyed due to anthropogenic climate change. The torrent of ecological disasters sees a rise in the rate of climate migrants as people are forced to leave their homes due to rising sea-levels, storms, and flash floods.

Adapting our relationship to the nonhuman world in the light of the climate crisis requires substantial changes to our practices. The world we know is changing whether we change with it or not, becoming more unheimlich and unhomely as the effects of anthropogenic climate change leads to a lost or damaged connection to place. Environmental studies are sometimes accused of hyperbole and alarmism, but facing the effects of anthropogenic climate change is imperative in order to effectively navigate the world around us and our position in relation to the nonhuman in the future.

Liam Bell is a Post Graduate Researcher (PGR) at Cardiff University researching in the field of environmental criticism and the Robinsonade. Liam is also co-chair of the Modern and Contemporary PGR group in Cardiff.