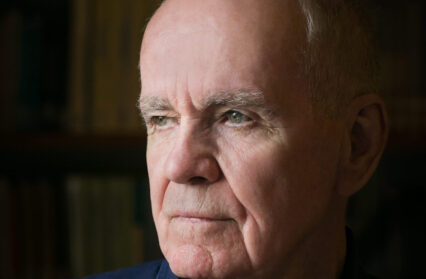

Matt Jones remembers a literary great and reflects on the expressive power of syntax and vocabulary in the writing of Cormac McCarthy.

The late Martin Amis said of Elmore Leonard that ‘all his thrillers are Pardoner’s Tales, in which death roams the land’. The same is true of Cormac McCarthy, whose loss at 89 is momentous. McCarthy is a direct descendant of the great American modernists, Faulkner and Hemingway, as seen in a lack of punctuation and Faulknerian sentences which span an entire printed page or more.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of his writing, however, is the expressive power of the syntax and vocabulary, as akin to poetry as it is to prose, and which owes as much to The Book of Revelation as it does to Hills Like White Elements and As I Lay Dying. When McCarthy holds forth, he does so like John Milton crossed with Dylan Thomas channelling a Pentecostal preacher, a lava-like torrent of words, as awesomely elemental as the meteor shower in which ‘the kid’ in Blood Meridian is born.

Unlike his literary forebears, McCarthy also wrote genre fiction, specifically westerns. The great romance of the American west has been hugely compelling for generations of nature-starved city dwellers the world over, but the myths of the western have long since been debunked as white male fantasies. It is fair to say that McCarthy is characteristic of this late-Twentieth century revisionism, but even fairer that, in his hands, the genre becomes a vehicle for his philosophical and existential concerns, such as the stand-off between good and evil, but also his reflection on the transient nature of things.

The reason why McCarthy’s work resonates so powerfully is that it engages directly and unblinkingly with the human drama and the extremes of kindness and cruelty, good and evil. He invites us to consider the enduring paradox of man’s inhumanity, not just to man but, perhaps ironically, to wild animals. Some find it hard or impossible to read the gorier passages of his work, but in McCarthy, violence is a given, an absolute. If the humans in his stories behave inhumanly, then that is because it is inherently human to do so. Alternatively, the savagery meted out by the likes of Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men is seen to be a vestige of something bestial and therefore natural. Nature in McCarthy is something to be valued and feared but never to be separated from the human condition.

One of the most compelling aspects of McCarthy’s work is the wraith-like qualities of the characters, often tenebrous, insubstantial, sometimes accompanied by a mysterious ‘third’ presence, a kind of ghost image or corona effect. In Blood Meridian, when the fearsome Glanton Gang descend upon Mexico amid a thunderstorm, the conjoined shadows of horse and rider cast by the lightning are described as ‘some third aspect of their presence hammered out black and wild upon the naked grounds’.[i] Again, in Cities of the Plain, when a destitute Billy Parham is taken in by a concerned family, we hear of a photograph of the family’s ancestors, printed from a broken plate, and where the sitters had been pieced back together, ‘apportioning some third or separate meaning to each figure seated there’.[ii] Life, it seems, is ‘but a walking shadow’. He may be reprising Macbeth, and by association, Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, although I think of McCarthy’s ‘third aspect’ in terms of William Hughes Mearns’ Antigonish. Like the man upon the stairs who wasn’t there, his characters are both present and absent.

The western possesses an elegiac quality, a sense of longing for things past – or more accurately, a sense that things are always passing – to which the valedictory tone of McCarthy’s work is ideally suited. Sheriff Ed Tom Bell starts each chapter of No Country for Old Men bemoaning the passing of ‘the old ways’. Even as Llewellyn Moss (No Country) and John Grady Cole (All the Pretty Horses) are saying hello, they are accompanied by a ghost image, waving goodbye. It is commonplace for characters to be haunted by their past, but in McCarthy, they are also haunted by their future. Both Llewellyn and John die in extremely violent circumstances. If Death roams around McCarthy’s stories, and violence is a fact of his fiction, then so too the reality of our temporary home, the world.

For Cormac McCarthy’s work also has a strong social and moral conscience. He often features poor white southerners, such as John Wesley Rattner, the hero of his debut novel The Orchard Keeper, who is taught to live off the land by old Arthur Ownsby, only to discover such skills are of little use to him in the modern world. Not all of McCarthy’s protagonists are white and working class, but most of them are, and this may be because the hardships of the human drama are most keenly felt by those at the bottom of the social scale. Granted, John Grady’s grandfather owned a ranch, but The Gradys are déclassé by the start of the story when John sets off on his coming-of-age adventure. It is hard to say where in life Llewellyn Moss started out, but he’s a Vietnam Vet who lives in a trailer, so, the chances are it wasn’t on the upper rungs of the ladder.

Form and subject are inseparable in Cormac McCarthy. A testimony to this implicitness is that, while some novels may be easy to adapt, others are almost impossible. When asked how they adapted No Country, the Coens famously remarked that one of them read the book aloud while the other typed it into the computer. This isn’t strictly true, but it makes for good copy, and the relentless pursuit of Llewellyn Moss by the demonic Anton Chigurh makes for good cinema. The same cannot be said for Blood Meridian, which has thwarted many attempts, most recently by James Franco, although there is talk of John Hillcoat, director of The Road, adapting it soon.

When he does, he will have to find a way of visualising what is effectively an epic poem, rich in imagery and allusion to fire the reader’s imagination, but to present the sternest of challenges to storyboard artists, scriptwriters, and cinematographers. Will he succeed, or will a text made up of Shakespeare, Faulkner, and The King James Bible resist his efforts, and the old ways prevail? Time will tell.

[i] Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, London: Picador, 1990, p.151

[ii] McCarthy, Cities of the Plain from The Border Trilogy, London: Picador, 2002, pp.1036-1037

Matt Jones is the lead singer of The Hepburns, whose latest album, Only the Hours, is available to stream now on Bandcamp.