Dai Smith reflects on the life and career of Max Boyce, making the case for his place in the cultural Pantheon of Wales.

At the age of seventy-eight Max Boyce has become a cultural icon. He has been a cultural phenomenon since his career took off with his surprise-hit, best-selling Album Live at Treorchy in 1973. It was a moment for which his particular genius was made: an instance of historical triumph poised between the successful miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974 whose significance, the first national victories since 1912, he understood in his bones. The comedy with which he regaled that Rhondda audience was salted, as they were, by knowledge and revenge. They didn’t need to be told “Duw! It’s Hard. It’s harder than they will ever know” because, like Max, they knew who exactly the ignorant “They” were. They also knew that what coalmining had extracted from families and communities was as deep as it was still raw.

Nor did wider audiences, quickly picking up on his spreading fame, need telling that “the pit head baths are a supermarket now” since, as South Wales stumbled on into the 1970s, the evidence was all around them. A known and cherished world was literally slipping away as collieries continued to close and valley townships shrivelled further. Hence that historical, shudderingly hysterical, pause in 1973 as the momentary, yet momentous, industrial fightbacks sandwiching that year first rocked the Tory government and then caused an electoral defeat. The laughter ricocheted outwards from Treorchy until it returned as a ghastly echo in 1984-5.The enigmatic career of Max Boyce, its ups and downs, glints for us like a cracked-open lump of anthracite coal to reveal the social fissures of the past half century.

He was born in Glynneath in September 1943. His father, Leonard Maxwell Boyce, originally from Ynyshir in the Rhondda Fach, had died a month before in a pit explosion in Onllwyn Colliery, Banwen in the Dulais Valley. Four men had been badly burned in the Evans and Bevan colliery but, as the management told the local newspaper: “The damage was not extensive, and work was resumed shortly afterwards”. Leonard was, in fact, fatally injured and his four workmates were hospitalised. A subsequent case, a year later, against the colliery owners for negligence for “failing to provide proper ventilation at the place where the men were working” was proven and admitted. Mary Boyce, Len’s thirty year old widow, was awarded “£1,750, of which £300 was for a year old child, with £23 funeral expenses and costs”. The Boyce family would never need to be reminded of the price of coal. The sum allotted for the child was about the total wages for a whole year of a skilled collier.

The boy would leave school aged fifteen and, variously, work underground and as a factory electrician, then studying for a time to be a mining engineer at the former School of Mines on the campus at Trefforest. In the 1960s Max’ personal need for expressiveness would be assuaged by reading poetry, versifying in his back bedroom and singing amateurishly in local clubs in the Folk and Country mode of West Wales and West Virginia. An uncertain direction of travel, both for him and his creaking industrial society, was counterpointed by strong roots. All around the young at that time were the examples and values of men and women who truly knew where they had come from and exactly how they belonged to one another.

The new generation, increasingly so, might never again be of a coalmining or steelworking background but their parents and grandparents had been the makers of their own community genesis, and they personified a moral compass not to be ignored. The unspeakable -because avoidable -obscenity of Aberfan in 1966 was bookended by the numbing effects of pit closures – “And it’s they must take the blame” – and the working-class struggle across all the coalfields of Britain which restored miners to the forefront of the league table for industrial wages until, after attrition, the NUM was outwitted and outgunned in 1985. Max Boyce’s song title teased out the process of implosion with a scepticism attached to regrets for so much that was expended in vain: “A Winter Too Late (Miners’ Strike Song 1984-85)”:

Did you listen then to Arthur

Do you think he was misled

Did he lead the miners bravely

Or was he much too vain

Would he call a ballot

If he had the chance again

And when the year had passed ,lads

Did you wonder was it fate

That brought the bitter weather

A winter just too late.

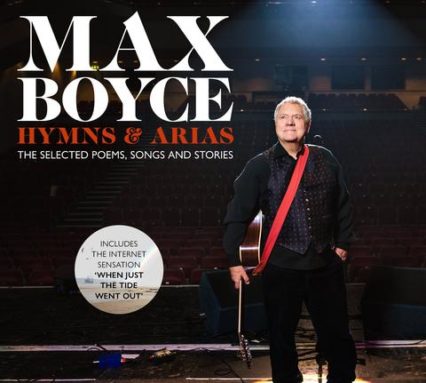

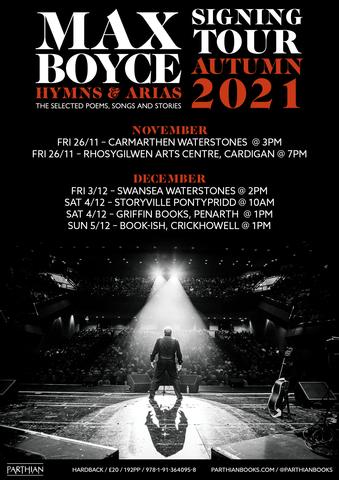

As an Afterthought to Hymns and Arias (Parthian, 2021), his latest collection of songs, poems and stories – there were two previously, in 1976 and 1980 – Max reflects how “Some of my work has gathered dust on the shelves of time” since they “belong to an age that has passed”, but that they are included here since, too, “they are of a certain time and place that is worth remembering and precious to me”. Indeed, running through this Collection are elegiac tones resounding in deceptively simple rhythms and rendered in a diction which recalls the great poet of the earlier coalfield, Idris Davies (1905-1953). But the fissures do not all break sadly.

The self-confidence of Max’s post-war generation shines, too, as a celebration of life served up for a relishing of its cultural particularities in tall tales, anecdotal jokes, ancestor worship, and, of course, the concomitant triumphs, and very rare tribulations, of a glittering era for Welsh Rugby Football. His rocket-ride to fame coincided with that sporting glory and imprinted him with the sobriquet readily bestowed upon him by Gareth Williams and myself in 1981 in “Fields of Praise: The Official History of the Welsh Rugby Union” where we called him “The popular Troubadour of Welsh Rugby”. In the 1970s, a decade sprinkled with Grand Slams, Triple Crowns and victories against the All Black Nemesis via Llanelli and the Welsh dominated Lions, Max Boyce was the jubilant ventriloquist of a travelling army of carousing, worshipping, gobsmacked, bobble-hatted, joyful supporters. From treasured and closely guarded icons, those much-fingered “photos of Barry John” to “A Sunshine Home in Dublin for blind Irish referees”, and on to predatory Ladies of the Night who wanted your Ticket or Debenture for favours bestowed, Max mercilessly laughed at and with a delirium of croaking tenors belting out the oh-not-so-PC “Delilah”.

The good times roll again in this book, its hilarity buttressed by photographs of him in performance and by the architectural and typographical lattice-worked cartoons of Gren. In short order, he sold over two million albums world wide. He made TV series as a singer, comedian and genial presenter. He packed the London Palladium. He toured the UK to poke fun at the po-faced. He sold out the Sydney Opera House. He just seemed to have been made with precisely that time in mind.

There was more to it, however, than talent and timing. He, and his echoing admirers, were facsimiles of the Rugby XVs they invested with more than a touch of glory. Teams were transformed by them into Standard Bearers: as in reports of Captain Phil Bennett’s impassioned exhortation to his men in 1977 before they played England to take historical vengeance on a field of play against the white-shirted emblems of rapacious capitalism and imperialism. It was an opera bouffe act in a melodramatic Revenge Cycle. The style, the victories, the arrogance of assumption, the God-given DNA—that underground factory where a conveyor belt of Welsh outside halves were made until, tragically, they “cracked the mould of solid gold that once made Barry John”—all the attributes railed against were, clutching an oval ball, nowin unlikely Welsh hands. And the hands were, more often than not, the hands of the sons of coalminers and steelworkers—from the coaching genius of Carwyn James to the wizardry of Gerald and Gareth and Chico and Barry and Denzil and JJ and Arthur Lewis and John Bevan, and on and on, even to the gnarled resistance of working miners like Glyn Shaw and that incomparable Everyman, Dai Morris who was called Shadow by his team mates, the one no one ever “blamed”, the one the children all called “Dai”.

It could not, of course, last. Before the mid 1980s the fever pitch of an unending, assumed continuum had petered out for coalfield society, its holistic way of being, its industrial muscle, its sporting triumphs, and for Max himself. There is a poignancy in what he considered his proudest moment, when he heard the crowd in the North Stand of Cardiff Arms Park sing out his “Hymns and Arias”, that lusty lament for the actual hymns and anthems once sung with natural spontaneity. The replacement of “Calon Lan” and a hallowed back-list was a bittersweet irony which signified an unspoken truth, that the paraphrase of memory had replaced the poetry of being. For Max, in mid career, there were necessary shifts in tone and emphasis, on stage and on air, foregrounding the exaggerations of the cheeky chappie front-man, an Innocent Abroad from Back Home.

But the connective nerve ends were too often frayed from then on. He sometimes looked and sounded like a relic of a past time. The surface characteristics which had amused in his act, cut loose from the hinterland of a vanishing actuality, could seem like the unwanted caricature his detractors resented. The outsized rosette. The giant leek. The Scarf, the Bobble Hat, the drawn-out accent and pantomime gestures. Not so much an archetype of a distinctive community and more a stereotype of a diminished working class. He was being unpicked just as his rooted world was not just being shrunk bit by bit but found itself systematically dug over by the denizens of Thatcherism and all that was thereby entailed. His own limitations, though always readily understood by himself, were sharply exposed: as a folksinger he leaned heavily on the traditions, and as a personality on screen his touching eagerness to please could be over ingratiating almost to the point of being schmaltzy. In late 1980, in the magazine Arcade: Wales Fortnightly which was invented to turn the cultural tides, Kim Howells, spokesman for the NUM in the 1984-5 strike, wrote acerbically about a perceived “shabby sentimentalism” and a “maudlin fatalism” in the social victimhood he detected in Max Boyce.

He was not alone in that opinion at that fraught, murky time. What was being expressed was a more profound cultural unease with the generally celebratory tonality of our popular culture. The South Wales coalfield, with its stirring male choral tradition and its drilled silver and brass bands in the first, massed ranks of its musical presence, from Victorian times had never embraced the lone voice, the plangent accusations of the subversive Balladeer. Ours was the music and the lyrics of heroic Romance and soulful Melancholy, of individual and communal fusion in common cause, not the strangulated defiance of the oppressed and the bitterness of the overlooked. In short, by the time we had reached mid century, Billy Connolly had never lived here. Sentiment, if not sentimentality per se, was a comfort blanket we held close, one knitted with the maxims of religiose nonconformity in as Protestant a part of the Bible Belt as you could find outside that other Deep South.

What this viewpoint saw, however, was much less than meets the eye if we adopt a longer and deeper perspective. The Act which Max Boyce had fashioned over the years was, like its attendant society, a masterclass in survival technique. The traits it exhibited to the prissy discomfort of some native onlookers would, in a further passage of time, only need fine tuning to let their undeniable authenticity shine through the framework of performance once more. The nub of his ability to engage and hold an audience was entirely performative. He was, on show, the classic Trickster Supreme. He subverted the secure reality they owned by aping its absurd self-satisfaction. His moon-faced, rubbery-visaged, wide-eyed helplessness, trembling between tears and chuckles, lulled you into his Simple Simon disguise only to trick you with a sly cunning for the payoff line. Having trumped cheerful expectation, there might be a sardonic comeuppance for the self-inflated, the socially superior. He pricked pretension. He deflated the self-regarding. The Clown, claiming innocence through feigned ignorance, chided all manner of snobbery.

Max, in this mode, was a great Clown, and like all such he was haloed by a protective ring of knowing sadness. To act the Fool in a world at odds with all sense was to be other than foolish. Gwyn Thomas’ Dark Philosophers emerged from the ruins of the 1930s to engage with the deceit of sobersided truth by means of zany humour. It was a Welsh weapon. Max was in the tradition of Caerphilly’s Eynon Evans who used surreal comic capers to create the radio sensation, ”Welsh Rarebit” ,from 1938 to 1941, which peaked across all of Great Britain with fourteen million listeners in 1949. The antics of not-as-daft-as-he-seemed Tommy Trouble and Wyn Calvin’s camp signature opening of “”Elloo, Boys!” had a later personification in Max Boyce.

During that unifying wartime period in which his father had died underground, ”Welsh Rarebit” had a weekly “Letter from Dai” as part of its American-style mix of fast-moving, kaleidoscopic sound. It was written and read by Lyn Joshua, son of the evangelist Seth Joshua, as a heart-tugging account of the daily life of the various Welsh home towns of the listening soldiers serving overseas. The programme always ended, tear ducts fully opened by then, with the glycerine sweetness of “We’ll Keep a Welcome in the Hillside” for those who, one day, would “Come home again to Wales”. The specially composed music and words were, respectively, by the show’s talented Producer, Mai Jones and by Lyn Joshua. Its incantatory melody and unashamed, gushing lyrics of hiraeth and home, might have been written by Max himself, then or later. This was the popular cultural zeitgeist of South Wales. One to inherit and to take forward.

Max would have been old enough to see the last days of Variety Theatre and the so-called Comic Turns which enlivened it in venues like the Empire and the Grand in Swansea, and in theatres across the coalfield before they became cinemas towards the end of the 1950s. There were star names on the Playbills: the fishwife cackle of Gladys Morgan, the come hither innuendo of Maudie Edwards, the gurning tomfoolery of Stan Stennett, all known from the airwaves. Their humour refracted rather than reflected an ambient world of neighbours and over-the-garden-wall rivalries. Live performance, local performance, audience and artist in tandem were the filaments of a common popular culture. Perhaps the most distinctively formed of all those variety performers was Ossie Morris (1906-68) from Port Talbot ,and a worker in the steelworks until sudden fame in 1949 catapulted him from Workingmens’ Clubs to being the resident comedian on “Welsh Rarebit” and a top of the bill act across, though not beyond, South Wales. Ossie brought something additional, a humour which verged on the control of insolence. He could be silent, near to sarcasm in a louche persona, before unleashing his wit on his captives. He told us to wait, be patient, to be quiet if we wanted to listen, and even learn: “’Ush!” he’d say, “I must ‘ave ‘ush!”. His every fibre, the suggestion of drink taken and deeds to be kept hidden, was cloaked in a questionable aura of respectability. He was from us and for us, the grown-up antithesis of what being a tidy boy meant. The laughter he evoked had, of course, the catharsis of release but, more, it invoked the consciousness of lives lived amongst promises endlessly deferred. Neither he, nor we, were in the business of kidding ourselves.

Through observation, or by osmosis, Max Boyce conveyed the same message. For his poems and songs in the 1970s he had needed that intimacy of connection which, in that decade, he had found to such memorable effect. He knew all along how it had come about. In the Foreword he wrote in the summer of 2021 for this third collection of his work he summed up his creative process:

I put my songs and stories into the furnace of performance, altering a line here and changing a word there, until…they are the best they can be and best suited to the gifts I may or may not have… These are the poems and songs and stories formed in the embers of that furnace.

Now some may consider it coincidental, but I certainly do not, that those performative, flickering embers burst back into spectacular flame again a year after Wales turned a tricky corner and, in 1997, voted to go on the journey heralded by Devolution. The “old” Max had been rather quiescent for a while, just as his formative society’s culture had been dimmed to a shade of its former self. Yet the connective tissues from past to present were clearly vital lifegivers if any meaningful future was to be envisaged. The validity of a generational hands-on was essential to help revivify values. As a member of Max’s own generation, I had skin in this unfolding game.

In the 1990s a part of my commissioning strategy as Head of Programmes (English Language) at BBC Wales was to reach out, across all broadcasting genres, from News to Sport to Drama and Documentaries, to acknowledge the cultural requirements of an audience too much deprived of a full sense of themselves on the airwaves of radio and television. Entertainment was no exception. So, in the absence of a “Welsh Rarebit”, we found a contemporary resonance in the comic devilment of Owen Money and the unforgiving, satirical pirouette of Boyd Clack’s “Satellite City”. And then there was the figure waiting in the wings, the “new” Max Boyce. It was Chris and Megan Stuart of the independent company Presentable Productions who approached me to suggest a Max Boyce Special for BBC Wales. He did not want to re-tread his material. He envisaged a different version for a changed time. In conversation and in discussion with all concerned, he was fully engaged and what emerged for a Christmas Special in 1998 was a pared down, stripped back, in-your-face and furnace-refulgent Star Performance. The show broke all BBC Wales records for viewer numbers. The audience had been waiting for this, and Max in a spectacular act of reconnection did not disappoint. Audience and artist knew who they were and why they were for each other. It was Maximum Boyce.

As the twenty first century began in Wales, with Millennium celebrations and the opening of the Welsh Assembly, Max became a singular and connecting bridge from what had gone to what might yet be in the future. His was a constant presence and reminder. If songs and poems could be measured for audience impact as much as for sheer literary worth, then the academic historian Martin Johnes was surely right, in his compendious volume of 2012 Wales since 1939, to assert that Max Boyce’s “Duw! It’s Hard” had become “as important to Welsh culture as anything written by Dylan Thomas or Saunders Lewis”. The connective tissue was the real deal as Max had demonstrated over and over. Or else there was only the nothingness of solitary existence and the know-nothingness of throwaway individuality. Wales was not immune from the blight of social amnesia. Remembrance, then, was always more than nostalgia. The elegy sung is also the eulogy proclaimed: from child to father and mother and forbears through generations. And the colour of that saying is neither to be bought nor found except in the human traces it has left, for the colour is indelibly Rhondda Grey as in Max’s great song/poem of that name:

One afternoon from a council school

A boy came home to play,

With paints and coloured pencils

And his homework for the day.

‘We’ve got to paint the valley, Mam,

For Mrs Davies Art.

What colour is the valley, Mam?

And will you help me start?’‘Shall I paint the Con. Club yellow,

And paint the Welfare blue?

Paint old Mr Davies red

And all his pigeons too?

Paint the man who kept our ball –

Paint him looking sad?

What colour is the valley, Mam?

What colour is it, Dad?’‘Dad, if Mam goes down the shop

To fetch the milk and bread,

Ask her fetch me back some paint –

Some gold and white and red.

Ask her fetch me back some green,

(The bit I’ve got’s gone hard.)

Ask her to fetch me back some green;

Ask her, will you Dad?’His father took him by the hand

And they walked down Albion Street,

Down past the old Rock Incline

To where the council put a seat,

Where old men say at the close of day

‘Dy’n ni wedi g’neud ein siar’*

And the colour in their faces says,

‘The tools are on the bar.

The tools are on the bar.’‘And that’s the colour that we want

That no shop has ever sold.

You can’t buy that in Woolies, lad,

With your reds and greens and gold.

It’s a colour that can’t buy, lad,

No matter what you pay.

But that’s the colour that we want:

It’s a sort of Rhondda Grey.’‘It’s a colour that can’t buy, lad,

No matter what you pay.

But that’s the colour that we want:

They call it Rhondda Grey.

Max Boyce has earned his place in the Cultural Pantheon of Wales.

Max Boyce: Hymns & Arias – The Selected Poems, Songs and Stories is available now via Parthian.

Dai Smith is a cultural historian, novelist, author, and broadcaster.

_______________________________________________________________________

Recommended for you: