I first came to love David Jones through my father, who kept pace with the increasing volume of publications both by, and later about him, until the 1990s. How he would have loved this book: it is both readable and revealing for someone new to David Jones, and for those already enthralled by the work of this deeply committed man, it is full of insights and new information. Dilworth draws on his own memories of visits to Jones when he was in his twenties, and refers meticulously to many other sources to supplement his own observations.

I was arrested by some of his words in the Introduction:

‘In this book I hope to dispel forever the assumption that he simply enjoyed the war and suffered no negative consequences from it… It was followed by four decades of depression which he was only partly able to counteract by creative work… That he finished all this work while experiencing his own dark interior aftermath of the war establishes him, I think, as a hero of the creative imagination.’

There are two aspects of this book which I found most illuminating, they are both specific to David Jones, and universal to the whole generation of men who endured the war. Firstly, how, or to what extent, an artist is affected by terrifying experiences, and whether they are exorcised by attempting to express them, or whether this activity has the ‘negative consequences’ of embedding them more securely in their memory and imagination, which, it seems, happened to Jones. Secondly, how earliest experiences and interests exert a lifelong influence on an artist’s work, which in Jones’ case is shown to be true. This book deals with both of these aspects (and many others) in a way which is both scholarly and immensely readable.

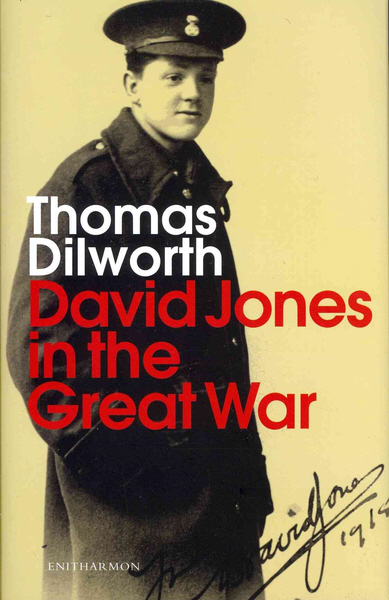

by Thomas Dilworth

London: Enitharmon, 228pp

Dilworth notes on several occasions how, because of the disparity of their experience, soldiers on leave found it almost impossible to talk to those back home who had not suffered in the same way.* Those who had been, or were going through, this war were often not able to find a way to express the burden of their experiences which would touch someone who had not undergone their traumas. This was a feeling shared by other poets who soon became dissatisfied with the pastoral and romantic poetry which preceded the war.

We learn how Jones, who carried a poetry book with him despite the extra weight, became impatient with the writings and words of those who had not shared a soldier’s trials. His kinship with fellow soldiers is shown in his drawings (many published here for the first time), and we learn that as the war dragged on, and so many were killed or maimed, he could not bear to draw them, and turned to guns or ruined villages. After the Armistice, and a posting to Ireland, he was able to draw his comrades again, although throughout his life he would be haunted by memories of the wounded men. ‘The memory of (them) is like a disease to me.’

Before the war, Jones was taught by A S Hartrick in Camberwell School of Art, who made him aware of drawing in two ways: in broad line with tone, as in his sketches, and in a finer line, a technique which he would later use in conjunction with watercolour washes and gouache; it was Hartrick who published one of his drawings of trench life, which he had sent back from the Front.

The first chapters illuminate so well how Jones’ early reading and aesthetic inclinations underscored all his subsequent work. As a child he was exposed to the language of the Prayer Book, and ‘by the time he entered the army he had already read the works by which he would interpret his war experiences in In Parenthesis.’ We also learn that he was delighted to find that his early reading concurred almost exactly with that of C S Lewis. Jones observes that he was not the only one to feel a continuity with soldiers of the past, and thought that ordinary Welsh soldiers were more learned than their English counterparts. Jones felt his Welshness deeply, and to belong to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Dilworth suggests, this was in effect ‘a nomadic homecoming’ for him.

From Dilworth’s many original observations, we learn that Jones displayed an early fondness for interwoven things, a characteristic which was to permeate all his work. For several periods during the conflict, he was engaged in map-making, which he liked, and observed the ‘complex meander of entrenchments’. Dilworth describes one frightening experience when, against orders, Jones took off his boots to sleep. On being suddenly awakened by gunfire, he had several moments’ panic while trying to find both boots in the dark: This experience re-surfaces in the frontispiece to In Parenthesis, which depicts a soldier with only one boot.

Jones was able to find beauty even in the appalling conditions: he describes how he noticed a coloured label on a German ‘dropt stick bomb’, and Dilworth observes that even battle could not suppress the aesthete in him. His drawing of dead rats must count among the most poignant of his sketches. The event which Dilworth describes in detail and refers to as an ‘epiphany of beauty and transcendence’ was his chancing upon Mass being said in a barn; this was an experience both aesthetic and spiritual, and which led to his being received into the Catholic Church in 1921. All these details bring David Jones to life, and are critical to an understanding of how he wrote In Parenthesis.

This book gives a vivid and highly readable account of a man who, in the terrible circumstances of war, remained true to his earliest sense of vocation as an artist; through its pages we come to realise what its re-creation in poetic form must have cost him. It explains vividly how his early love of history came to permeate his art and his poetry, illuminating the backgrounds to his work whose subtlety and scholarship has always defied an easy interpretation.

* In his book Into the Silence, (Vintage, 2012) Wade Davies quotes Herbert Read’s thoughts on returning home on leave: “between us was a dark screen of horror and violation…we left the war…dazed, indifferent, incapable of any creative action…” (p 198) He also describes how Robert Graves, shell-shocked, “remained mute, as did so many of his generation, simply because language itself had failed them.” (p92) Words did not exist to describe what they had endured.