It’s been a year since theatres up and down the country closed their doors indefinitely. To mark the occasion, Adam Somerset reflects on the artistic vitality of live productions, and explains why digital theatre will never supplant the physical experience of live staged productions.

On 13th March 2020 the doors of Aberystwyth Arts Centre closed. They — along with the myriad of performance spaces big and small — remain locked. The time for their unlocking, their return as places for our collective mingling, is unknown. Theatre is a place, a seeing-in-a-place. Its origin in Greek, “theatron”, denotes a spectacle or a place for viewing. “Theasthai” means to behold and the root “thea” means variously a view or a seeing or a seat itself. Conceptually, “Eisteddfod” is similar, its root “sedd”, a seat. In the most elastic, and durable, of art forms there does not even need to be much seeing. Hattie Naylor wrote a play in 2012 for Sound and Fury titled “Going Dark.” It toured within its own performance box and was almost wholly, and brilliantly, without light. Theatre need not be a seeing-in-a-place, but it is a being-in-a-place. Its first and most important condition is that it features the company of others.

On 4th December 2007, a press release came from the Wales Assembly Government, (as it was then called). Its subject was the formation of a new national theatre company. It read:

This ambitious commissioning and producing structure will give a national focus to the theatre sector, keeping our stories, writers and questions to the fore… Civic life in Wales will be enriched; the cultural profile of Wales will be raised; and related art forms such as film, will also benefit.

Yet, theatre is not in direct relationship to film. It has employment in common, for vastly greater reward, with actors, designers, wardrobe and so on. Beyond this, they are vastly different entities. The best guide to acting in film is a short book from a source that might surprise some. Michael Caine’s Acting in Film: An Actor’s Take on Moviemaking was published in 1990 and says it all. Acting for stage is about the body. The camera, conversely, has small interest in the corporeal entity. Hollywood A-listers come, now and then, to the London theatre. Some, like Dustin Hoffman or Brian Cranston, have triumphed. Others have belly-flopped. Their acting has lost fluidity and variety of bodily expressiveness from years in front of the camera. Three fall-back postures or gestures are insufficient for the stage. The lens, silicon-based, is immobile; its field of view is restricted, its image form is rectangular. The eye, carbon-based, is a roaming globe with a two hundred and seventy degree span. Its capacity for data receptivity is vast. We are binocular where the camera is monocular. The carbon-based brain rewards us with richly textured representations of the environment rendered in three dimensions.

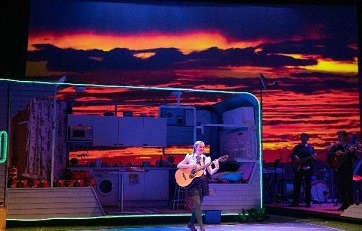

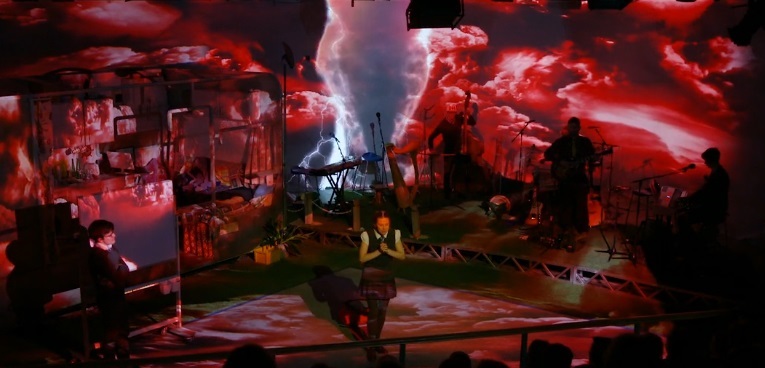

Design in theatre is made for this ocular reception in real space. Design in film is composed of a small number of receding planes. The camera flattens perspective. The filmed versions of productions from National Theatre Live are a huge service to the arts but they are, ultimately, a simulacrum. Sets are flattened, action is lost. The revival of Angels in America was the best kind of theatre for transmissions of this kind. Low in physical action, the play is mainly composed of two-person scenes; few other productions fare so well in 2-D.

Our physiology for hearing is not that of the microphone. Packet switching was invented by an undervalued hero of Wales, Donald Watts Davies, an engineer from Treorchy. (So too, to his credit, was the radical concept of using the existing telephone network for data). Packet switching featured one Sunday in 2020 in a radio interview with Trevor Cox, Professor of Acoustic Engineering at Salford. Cox explained why Zoom sessions make for hard work. Digital transmission uses packet switching for vision and voice data. Like it or not, said Cox, our perceptual apparatus was never designed for sampling the micro-interruption of voice. It works well enough as a simulacrum — for information — but real-world vocalisation comes through the oxygen-hydrogen mix that sustains us. It is not a sample but a continuous wave. Our ears are built for its continuity.

So too, said Cox, silence is different in the digital sphere. Absence of speech in the chemical-biological world is integral to meaning. Silence is the correlative of the word. The pause in noise gives the perceptual freedom to look at everything else that matters, the myriad of visual cues we are hyper-alert to. Master comedians are above all masters of the pause. Within the digital simulacrum silence does not contain meaning; it is just an absence of data.

Action in theatre takes place over continuous time and space. Action in film takes place in discontinuous time. The art of film — Pudovkin, its pioneer critic and theorist, said — is the edit. Eisenstein said in the 1920s, “montage is an idea that arises from the collision of independent shots… each sequential element is perceived not next to the other, but on top of the other.” The editor is the great co-artist of cinema. The greatness of Martin Scorsese is inseparable from the greatness of Thelma Schoonmaker.

Discourse on representation has a long heritage. Plato disapproved. Authoritarians like it but only on their own terms. Ludwig Feuerbach looked at the culture of his own day in the preface to his ground-breaking The Essence of Christianity. “Our era,” he wrote, “prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, the representation to the reality, appearance to being.” That was in 1843.

Susan Sontag was a fiery supporter of the greats of French New Wave cinema. She also made theatre in war-ravaged Sarajevo. In 1973, in the course of an essay on Artaud, she delineated the differences in art forms:

Unlike poetry, an art made out of one material (words), theatre uses a plurality of materials: words, light, music, bodies, furniture, clothes. Unlike cinema, an art using only a plurality of languages (images, words, music), theatre is carnal, corporeal. Theatre brings together the most diverse means – gesture and verbal language, static objects and movement in three-dimensional space.

Theatre is carnal, corporeal. Theatre presents a headache to policy-makers. It does not conform to economic orthodoxy. Economies of scale are elusive.

William Baumol, who died May 4th 2017, was given a commission to help those promoting the arts to understand the financial struggles facing cultural organisations. His report, co-written with William Bowen, closed with a simple but striking observation. Workers in the arts compete in the same national labour market as those in factories. Rising productivity in manufacturing lifts the wages of factory workers. But rising wages in the arts are not matched, as in manufacturing, by corresponding productivity growth: to perform a Beethoven symphony takes the same time and the same number of musicians in 2021 as it did in 1821.

Ever since the Northcote-Trevelyan reforms, the tradition of government in the United Kingdom has placed a high value on cogency and clarity of expression. This tradition within the Civil Service is eroding. This is an example as a composition from a public body.

Digital presents all sorts of possibilities in its own right for the making of art and opens up whole new means to ends. Some traditional and familiar tasks are transformed and wholly new possibilities are opened out. We will want to make sure our arts sector in Wales builds its capability and is innovating and path-finding.

This expression breaks with the tradition of government. Our philosophical heritage is empiricism. This assertion comes without example. The contagion of non-meaning has, thankfully, not spread far among real-world theatre companies. Nonetheless, an artistic director is still able to declare, “The digital allows us to join our work up and helps to pull together a network of people who connect to that wide range of work.”

If this means anything at all it is presumably about clicky-click comments. The meaning of theatre is its actualisation in three-dimensional analogue space. Ninety percent plus of people do not micro-blog. If a small minority mistake it as being congruent with the world-as-entity then that is a categorical error. Eighty percent of us are suffering disorders in our sleep patterns. The brain has not enough to do. A perceptual deficit is a consequence of enforced asociality, non-participation in the world-as-material.

Lastly, the Society of Authors held a Zoom session in December 2020 for those in theatre. It considered the effect of being forced away from public space. The panel was authoritative: Rupert Goold, Barney Norris, Mojisola Adebayo, Daniel Evans. An actor, Lin Sagovsky, commented, “It’s all quite strange for the actor… you can’t read your audience in at all the same way so although the community across continents is partly true, it’s also weirdly isolating as though you’re performing underwater.”

Loneliness is a scourge of modernity. Those who spend most of their time staring at a screen report the highest incidence of loneliness. Daniel Evans reported a medical study that showed t-cells get a boost from live performance – one that the tablet and the smartphone are unable to replicate. Theatre, one part of social co-presence, is literally, empirically health-enhancing.

Digital Theatre | The Creative Simulacrum Digital Theatre | The Creative Simulacrum

Adam Somerset is an essayist and a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Digital Theatre | The Creative Simulacrum Digital Theatre | The Creative Simulacrum