Americans choose to eat less than .25% of the known edible food on the planet.

–Eating Animals, Jonathan Safran Foer.

The first thing that Bête’s protagonist Graham Penhaligon says is to the cow he is about to kill: ‘Don’t call me Graham’.

The first thing that Bête’s protagonist Graham Penhaligon says is to the cow he is about to kill: ‘Don’t call me Graham’.

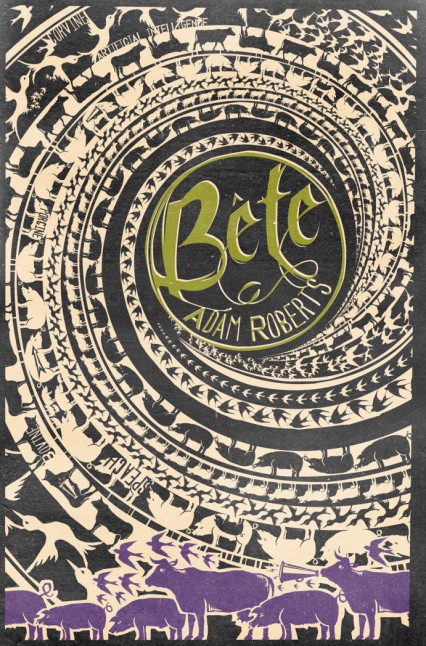

Yes, you did read that correctly: Graham is having a conversation with a cow. This is because, in his upcoming novel Bête, Adam Roberts imagines a sometime-future Britain, in which a rogue animal rights and ‘green’ activist group have fed micro-chips to farm and domesticated animals, causing them to appear to have human consciousness and communication abilities. Consequently, the farming or hunting of such animals, or ‘bêtes’, is in the process of becoming illegal, and the human-animal dynamic is thus changed completely and forever.

Graham Penhaligon is a cattle farmer and his livelihood is pushed to extinction by the advent of the new laws that would mean hunting or killing of bêtes would be considered murder. Graham, consequently, spends approximately two-thirds of the novel in a blind rage at the possibility of the new laws, and the effect this has on his life. This uncompromising and seemingly unfeeling protagonist does not endear the reader to the plight of human farmers, and as such, the immediate tendency to sympathise with human suffering is not encouraged. However, the narrative seems to deal with the bêtes’ characters in a similar manner. For instance, when Graham meets Anne, who is to become his lover, her sarcastic and acerbic pet cat Cincinnatus also enters the picture, and who, in rejoinder to Graham’s dislike of his presence, continually spouts typically feline smart aleck idioms and like Graham, does not exactly warm himself to the reader.

Despite the somewhat questionable and unlikeable cast of characters, as in much of Science Fiction, the issue of identity is raised in various forms. Not only is identity explored in terms of whether the micro-chipped animals can be considered in the same moral category as humans, but also in terms of artificial intelligence, and evolution. For instance, in much of Science Fiction, identity is raised either as an issue of the post-human (what current humans may evolve into), or in terms of alternate history (what humans could have been, or have come from). Roberts, on the other hand, seems to merge these two aspects of identity exploration, and combines the physical existence of animals, representing where humans have evolved from, and AI chips, representing where our technological enterprise is arguably taking us. The liminal identity of the bêtes between the human and the animal, between the organic and the technological, is highlighted by their title, also used for the novel itself.

‘Bête’ is the French word for ‘beast’, or ‘animal’, and within this word is the somewhat complicated and dual identity of a creature that has been artificially given ‘higher’ sentience. To think, for instance, of the word ‘beast’, or ‘bestial’ in English, is to imagine the baser instincts, the desires and needs formed and expressed by what Freud referred to as the ‘id’; visceral, basic, and raw. To think of the word ‘animal’ is to tone these associations down somewhat, though still to conjure images of the ‘dumb’ creature; one without complex thought, emotion, and of course, speech. Man then goes beyond both of these categories. Yes, man is technically both a beast and an animal, but somehow also transcends these definitions through technological advancement, through complex communication, and through manipulation of tools. In short, then, it is here that I would like to consider the importance of language, both in terms of how language is artificially supplied to animals in order to elevate them to the ranks of the conscious human, and in terms of how language is used within the novel’s narrative in order to call attention to the issues at hand.

In Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals, from which I quoted at the beginning, Foer relays an anecdote about a childhood babysitter who did not eat meat, and enlightened him to the fact that ‘chicken is chicken’. Foer notes that:

Her intention might or might not have been to convert us to vegetarianism – just because conversations about meat tend to make people feel cornered, not all vegetarians are proselytizers – but being a teenager, she lacked whatever restraint it is that so often prevents a full telling of this particular story. Without drama or rhetoric, she shared what she knew.

Here Foer draws attention to the fact that as a child, the term ‘chicken’ when applied to food does not necessarily conjure an image of ‘chicken’ as applied to the living animal. In a similar way, it seems that Roberts, by using the term ‘bête’ to signify an animal possessed with human communication skills and thought processes, calls attention to the lack of mental connection between ‘animal’ and ‘human’. This lack of connection seems to be a very British affect, and the love of certain ‘domesticated’ animals, such as dogs and cats is very much a part of British culture. It is in fact this particular domestication of animals to which Roberts seems to cling in his narrative.

The animals that Graham meets and converses with appear to be largely of the farm-bred or domesticated kind. The cow that appears at the very beginning of the novel, Graham’s killing of which begets his first problems with the law, is one that he has reared on his own farm. The most frequent animal voice in the novel – that of Anne’s cat Cincinnatus – is also a domesticated animal, and indeed a beloved household pet. In terms of killing animals for food then, Roberts draws attention to the fact that to kill an ‘animal’ – that is to say a non-speaking, ‘dumb’ animal – in order to eat, is considered by a large proportion of British people to be morally sound and indeed an important source of nutrition. However, when questioned, it is unlikely that this same group of Britons would advocate killing an animal that is considered a pet, such as a cat or dog, or indeed even killing a human for the same reasons. It is sentimentality, then, rather than a solid logic, that is more at work in this decision process. Ok, so cannibalism is not the same as hunting and killing another species, but to return to the semantic discussion of ‘beasts’ and ‘animals’, technically this would fall into the same category. Rather than presenting us with a narrative about cannibals, however, Roberts presents this issue from the opposite angle, instead presenting us with a world in which killing a bête is murder.

Much of the argument about whether man is ‘meant’ to eat meat, or whether vegetarianism is a preferred way of living comes down to religious doctrine, and again Roberts addresses this, largely through the character of Graham’s one-time friend, Jazon, who later goes by the name Preacherman. Preacherman is a devout Christian, and within the novel gives voice to the argument that within the Bible it is reported that Man is given dominion over all animals, and as such is permitted to hunt them for food, also claiming that, ‘The bêtes are signs of the incipient apocalypse’. The argument here is that since many religions permit the eating of animals (though many limit what kind, and how they are to be prepared) it is a sacred and ancient prerogative for man, and as such should be preserved and valued. However, in our modern world, other factors such as meat substitutions, as well as economic and ecological factors are more widely considered, due to the choice of food available in the developed world. Roberts does, passingly, reference this technological advancement, introducing the product of ‘Vatmeat’, a synthetically generated, much cheaper alternative to natural flesh.

To reference Foer once again, Eating Animals also approaches the subject of economics, and the need to be grateful for the food available to you. Foer tells of his grandmother, and her strong belief that one should savour every type of food, as her more impoverished upbringing lead her to view such choice of food as a luxury, and not to be taken for granted. It is true that in many countries across the world, the devastating lack of food for a huge proportion of people makes an argument about what should and should not be eaten a pantomime of ridiculous proportions.

However, in setting Bête in Britain, Roberts manages to work around this proviso, and address how we in the developed West can deal with the ethical and social implications of consuming meat. The economic state of Britain is slowly but surely torn apart in Roberts’ world of enforced vegetarianism. Animal farmers are put out of business, and a political war rages between the humans and tribal-style factions of animals, the largest being led by The Lamb – a sage and eloquent bête in the body of a sheep, over citizenship and ownership rights for the bêtes. This unrest ultimately causes the country to be split so that the country is inhabited by animals, and humans are rounded up into cities.

It is almost impossible to predict what effect the creation of such a law would have on the UK, but it seems that despite the large portion of the novel that Roberts dedicates to describing the situation, and to giving a hateful and unbending voice to his human protagonist, there is a separate issue at the core, here. As the narrative continues, Graham seems to become softer and more human. His love for Anne, and his eventual pact with animal-tribe leader The Lamb gives the reader hope that Graham might finally view the animal kingdom as more than a source of income, or as ‘dumb’ pets. Is what Roberts is getting at here, then, the theme of tolerance, and the idea that each human and indeed each animal is different, and as such will lead their lives in a different way? Some will eat meat, some won’t, but this binary categorization alone cannot determine a person’s moral fibre, nor can it predict how they will act when approached by a quick-thinking, philosophical sheep.