Industry of Tragedy – To celebrate this year’s International Dylan Thomas Day, we republish Gary Raymond‘s 2014 essay on the creation of the myth of the man, and the importance of that myth to the industry that has come from it with reflections from Christopher Isherwood and Kingsley Amis among others.

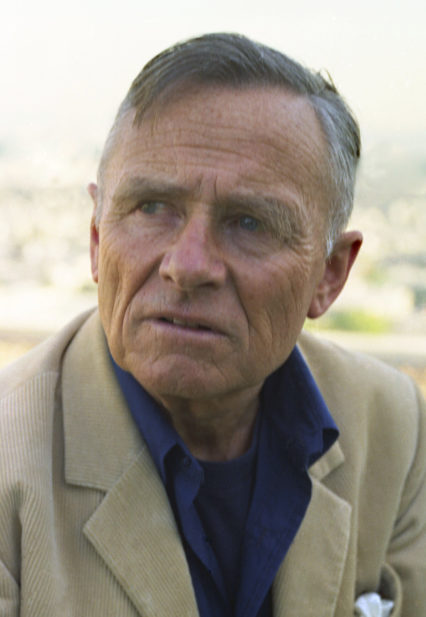

On December 8th 1953, almost exactly a month after the death of Dylan Thomas, Christopher Isherwood opened his diary to commit to posterity his encounters with the controversial Welsh poet. Stephen Spender had asked Isherwood to write a piece about Thomas, but Isherwood noted that ‘my memories were unsuitable for an obituary notice… But I’d better record them here, before they get too vague.’

Isherwood, who lived in Los Angeles and had done since fleeing with Auden England and the War in 1939, had rescued Dylan Thomas from the indifferent treatment of the English faculty at UCLA one April morning in 1950. Thomas and Isherwood had not met before, and Thomas, as was so often the case, was stuck, having been given only the number for a bus on how to reach the venue. Isherwood picked Thomas up from the ‘morning desolation’ of the bar at the Biltmore Hotel and drove him to the university where he was to give an afternoon reading. ‘The impression he made on me was,’ Isherwood wrote, ‘primarily, of struggle. He seemed to be right in the midst of his life – not off on one side looking at it.’

Dylan Thomas had started the day with drink, he drank some more during a pit stop at Isherwood’s house in the Valley, and then continued drinking at lunch as the guest of the English faculty. Isherwood remembers the ‘bogus, oily, sanctimonious’ academics at UCLA treating Thomas with ‘contemptible… prissiness’. Attracted to the dangerousness in his verse, they were turned off by Thomas’ performance in person, his lewdness and casual frequent deployment of the four-letter word; ‘It’s the attitude of the small boy,’ wrote Isherwood, ‘who would love (he thinks) to have the roaring tigers leap into the room out of his picture books, but who doesn’t want to be afraid of them if they appear.’

Thomas got drunk before the reading, but read beautifully – Isherwood was extremely impressed (elsewhere in his diary, many many years later, he watches Gielgud and Edith Evans recite some poems at a cocktail party in Hollywood and notes that they sounded like amateurs compared to Dylan Thomas). When the reading was over, the two of them escaped, Thomas now in excitable mood at the prospect of the entertainment Isherwood had lined up for him.

Dylan Thomas had wanted to meet a Hollywood actress – any Hollywood actress – and his idol, Charlie Chaplin, and Isherwood had used his connections for the two of them to have dinner at a restaurant with Chaplin and Shelley Winters. The meeting was either a disaster or a slapstick farce, depending on which way you look at it. Isherwood, ever the gentleman, tends to give Thomas, of whom he was clearly personally fond, the benefit of the doubt. But the facts remain that Thomas insulted Chaplin (enough for the auteur to mention it in his autobiography), before wrestling Shelley Winters to the floor over the back of her chair whilst trying to grab her breasts (Winters took it in very good humour, apparently).

Later on, when the party moved on to a bar on Sunset Boulevard, and everything became even more ‘muddled’ with booze, Thomas tried to fight a screenwriter who had been talking to Isherwood, taking a run up to him like a cartoon bull. Thomas was, famously, as quick to dive into a brawl as he was useless in the fight. He was repelled with great ease and ran into the night. Isherwood did not see him again until a chance encounter at the Chelsea Hotel in New York almost two years later.

And so, it seems, was a somewhat typical encounter with Dylan Thomas. And as is often the case, the confluent themes of such stories involved his drinking, his inexcusable behaviour when drunk, and the genuine warmth the memoirist feels for and sees in the man. That his legend has been built just as much upon these traits as it has on his work is irrefutable; that his legend would be less had his public story been different is also quite probable. The truth is that no twentieth century writer has a posthumous reputation of such standing that is so dependent on their behavioural legend like Thomas – even writers such as Plath and Woolf, whose disintegrations have attracted an industry of comment, have their biographies subsumed by their oeuvre rather than competing with it.

But here lies the inescapable truth of Dylan Thomas – his most vital creation was not in his work, but it was in his persona. The ‘Dylan’ that Thomas created was what allowed him to be the poet on the page that he needed to be, it facilitated the mining of his poetical gift: a perversion of what Yeats called the ‘antithetical self’.

Yeats wrote in A Vision of the two poles of the self, the primary, that which is ‘reasonable and moral’, and the antithetical, that which is ‘our inner world of desire and imagination’. The antithetical self is familiar to the writer of fiction, it is the business of the day; but Thomas utilised an antithetical self in order to survive, not only economically, hired out as a performing monkey to the bourgeoisie, but in order that he could live in desperate loyalty to the poetic truth that he committed to paper. In more ways than one, it was his antithetical self, that which created his legend, that allowed his primary self to write.

That this creation also proved his downfall is his most powerful claim to be the patron saint of the industry of tragedy.

The prejudices, embellishments and Chinese whispers that have gone into the sculpting of Thomas’ legend are a predictable offshoot of the life he first needed to live, and then became trapped by. It is extremely difficult to find any reminiscences of Thomas from his contemporaries – the people who first built his legend – that are wholly reliable; which is why Isherwood – one of the twentieth century’s finest diarists; compassionate, humorous, honest – is such a good place to start when looking.

Even biographers of Thomas, such as Constantine Fitzgibbon, are unreliable in their purporting of the Thomas legend, so in thrall as they so often are to their own ego and place in the developing narrative of legend-making that they elevate their own prejudices.

In Fitzgibbon’s case, an aggressive anti-communist, it is clearly difficult for him to hide his disdain of figures such as the ‘King of Bohemia’ and sometime affiliate of the anarchist movement, Augustus John, whose recorded reminiscences of his long-time friendship with Thomas (it was John who introduced Dylan to Caitlin) may not always be flattering, but they are at least disinterested in the moulding of any legend at all. (Check out passing jibes from Fitzgibbon when writing about John ‘… who, in those pre-war years, promised to become a great painter. That he failed fully to keep this promise was due above all to his extravagant tastes…’). Fitzgibbon takes similar snide shots at anybody else who did not find Thomas as entertaining as they were supposed to.

Fitzgibbon instead decides to align Thomas with the oddly correlative figure of Theodore Roethke, the big, womanising, alcoholic, German American poet, who likewise died prematurely (a heart attack at 55) due to his excessive lifestyle. (That Roethke, often referred to as the greatest American poet of the twentieth century, has not been subjected to the same canonisation as Thomas perhaps lies in America’s lack of need for yet another Hell Raising writer).

Roethke himself remembered Dylan Thomas, whom he knew and drank with for a relatively brief period in Los Angeles, as ‘one of the great ones, there can be no doubt about that. And he drank his own blood, ate his own marrow, to get at some of that material.’ They are powerful, passionate words, from one great poet to another, and in a small way, they elevate the writer of them as much as they do the eulogised. Nobody doubts the kineticism of the well from which Thomas drew his poetics, but here at work are the subtle cogs of myth-making. To champion greatness can create an exalted, esoteric pool in which recognised and recogniser swim together.

This is the starkest evidence that Thomas no longer belongs to himself, he belongs to that industry of tragedy; and it is an important part of the artists’ code, the thing that makes the world go round. (Thomas would no doubt be over the moon to see how he was adopted by the literati in his death as a totemic figure of artistic sacrifice.) Figures like Thomas are integral to the standing of the artistic community – the danger, the mysticism, the otherness. That so many people recognised the potential of Thomas the Legend and that so many chipped in to consolidate it after his death, is proof enough that the lucrative offshoot was cultural as well as fiscal. In poetry particularly, from Byron to Wordsworth through Clare and Swinburne to Pound and Plath, reputation for eccentricity and danger is priceless when viewed as sincere. Mix that with an early death, and a poetic destiny that somehow matches a writer of verse with an otherworldly essence, and you have an irresistible legend, one that reaches way beyond the readers of poems.

When writing the lives of Thomas’ friends and acquaintances, literary biographers have likewise been quick to use just the two dimensions of Thomas to draw something out of their own subject, often contributing to the skewed public character of Thomas himself. Arthur Koestler’s biographer Michael Scammell noted the attraction between the two fabled drinking partners as a ‘shared disregard for bourgeois politesse.’ Their eyes met across a crowded room and mischievousness sparked.

But Koestler was a brawler, a reactionary, a former vagabond who used to argue down Sartre and de Beauvoir into states of turpitude; Koestler was an intellectual giant whose oxygen was tearing strips off people in public drunken debate. Thomas was a very different creature indeed, although in his own way just as complex. To bind the two with their puerile scoffing adds colour to Koestler, but adds more monochrome to the picture of Thomas as parochial clown. Whereas Koestler was once described as a ‘noble goblin’, Thomas is most often referred to in later years as ‘puffy’. There is always a condescending tone, even from his acolytes, in many accounts of encounters with the bumpkin Thomas; perhaps if he had ever learned to land a punch, like Koestler or the fearsome Roy Campbell often did (the three of them making Soho their drunken playground during the War), Thomas may have been written about quite differently.

But it was the certainly more placid and decidedly more circumspect Stephen Spender who Thomas first encountered in London. Spender, in his Paris Review interview of 1980, which is bulbous with delicious anecdotes about his encounters with the likes of Yeats, Hemingway and Woolf, recounts his first meeting with Thomas. They have lunch in a pub in Soho, Thomas, Spender, and a friend of Spender’s, invited along to ensure awkward silences were broken up. And the friend is needed, as Thomas is nervous and pale and largely silent. This is the Thomas before he was the hired entertainment de rigueur of the socialite scene.

Spender pulls back to an overview of his relationship with Dylan Thomas; he tells how, many years later, Thomas wrote him a very warm letter thanking him for the hospitality Spender had shown him when he first came to London. And then Spender says: ‘He certainly said extremely mean things about me behind my back, of that I’m quite sure. I don’t hold that against him. It was just his style. We all enjoy doing things like that.’

Here we see the melee into which Thomas was flung in the days and months and years following that initial quiet lunch with Spender on arrival. The biting gladiatorial throng, so well embodied in the legends of the Bloomsbury Set, was in full flow, and Thomas was going to have to step up if he was to stand out. He certainly did that, as the story goes, by becoming more and more rambunctious and unpredictable, more shocking, the bumpkin Byron.

But was Thomas malleable to a scene, rather than stuck in one, or was he just ignorant and naïve? How calculated was this mask? His personal loyalties certainly seemed reactive, and not formed with one eye on the shifting winds. For example, Roy Campbell was persona non-grata with the Bloomsbury Set after his Georgiad lampooned the main figures, (that he was also prone to brawling, jumping on stage and swiping at Stephen Spender at a poetry recital, and throwing Jacob Epstein around a bar, probably didn’t help either). But when Generals Franco and Mola came up from Morocco in 1936 and sparked the Spanish Revolution, Campbell, a staunch Catholic, came out on the side of the brutal and murderous Nationalists, contrary to most intellectual opinion in England at the time.

Dylan Thomas, it seemed, ignored both the school yard spats and the rather more serious political standpoints of Campbell, and continued friendships on both sides of the divide. Campbell, many years later, wrote about his appreciation for Thomas’ lack of politicking in these matters; but one must consider Thomas’ loyalty to Campbell as perhaps being somewhat lacking in principle rather than smacking of it. Perhaps it was the loyalty of a friend, to stand by a supporter of fascism; or perhaps when John Malcolm Brinnin commented that Thomas’ socialism seemed a pose, and half-hearted, something simply expected from his Welshness, he was hitting the nail firmly on the head. Thomas, in the end, was ignorant of the politics, and he just sided with his drinking buddy.

Of course, Campbell and Thomas (and Koestler) had more in common than just alcoholism: they were always broke. Money, or lack of, is another heavy colour to Thomas’ story, and was the strongest compulsion in the creation of his public character.

It is worth noting here something of the character of the people who created the legend of Dylan Thomas. They were often those unfurled from the rarefied cloisters of Oxbridge, which further accounts for the condescending tone to which Thomas the person is often subjected in print. It also accounts for the tincture of vulgarity in Thomas’ portrait which goes beyond reaction to his brazen lewdness. Someone like Stephen Spender, who although hardly English aristocracy, came from a more entitled world than Cwmdonkin Drive, commented on how Thomas was ‘rather obsessed by money’ – ever the viewpoint of one who had rarely needed for it when looking to someone who was perpetually struggling to feed his wife and children.

Dylan Thomas worked hard to make ends meet, to put food on the table. Perhaps his refusal to do any work to which he was not physically or intellectually suited would be lambasted in certain circles (especially in today’s economically myopic censorious political climate), but in hindsight it is difficult to criticise his simple wish to feed his children using his talents, especially as they were so widely appreciated.

Thomas’ predicament, and his stresses, is displayed in painful poignancy in a brief correspondence with Graham Greene in 1947. Greene is an influential figure in the British film industry at this point, and Thomas tries to impress upon him an old script he had written about Edinburgh grave robbers Burke and Hare. The note soon degenerates into a begging letter. Michael Redgrave has shown interest in playing in it, he writes, before a ham-handed segue into a plea regarding his infant son’s medical bills and the writs that keep falling on the welcome mat. It is painful to read. Thomas wrote an uncountable number of such letters throughout his life.

What we see here is the reality of Thomas’ existence, and the strain it put on him. He was certainly not alone in his penury as an artist, but there was money to be made, one way or the other, in poetry during the thirties and forties, it’s just Thomas could not find a way into the middle-class hold. But he had something he had been inadvertently developing that he knew he could mine: his public personality, the antithetical mask.

And so as the legend began, it is quite remarkable how quickly Thomas grew to look at his new role, and the demands of it, as a curse.

Novelist and poet Rayner Heppenstall recalls one evening drinking with Thomas (Thomas downing some local Cornish moonshine), when Thomas breathlessly held court for quite some time before stopping and declaring rather sadly, ‘Somebody’s boring me. And I think it’s me.’

Already, the man trapped.

After his death, this very real need was turned into a romantic tragedy by Thomas’ contemporaries. Karl Shappiro wrote in 1955, ‘Thomas was the first modern romantic poet you could put your finger on, the first whose journeys and itineraries became part of his own mythology, the first who offered himself up as a public sacrifice.’

A sacrifice?! To the gods of poetry, no less!? A cursory reading of Thomas’ own letters shows clearly a man just trying to feed his kids. But Shapiro subscribes to an idea integral to Thomas’ legend when he goes on to write: ‘How much did Thomas subscribe to official Symbolism?… How much did he love death as his major symbol? As much as any poet I know in the English language. These factions have a claim on Thomas which we cannot fully contradict.’

But Thomas was not obsessed with symbols of death, because in some ethereal poetic bubble he could see his destiny in his posthumous legend. The compulsions of Thomas were far more earthbound, far more serious than intellectual legacy or celestial aesthetic vocation. It can be put quite simply: it was Thomas’ refusal to dig ditches for a living, because of his unquestioning belief in loyalty to his gifts, that meant he had to become a performing monkey for socialites and literati in order to feed his children; his alcoholism gained legitimacy not only as Dutch courage, but as part of his act, and his alcoholism gave him nothing in the tank when pneumonia came, and the pneumonia killed him.

And it was in death that Thomas was moved effortlessly, without his say so, from performing monkey to patron saint of the ever-vibrant industry of tragedy. For many years after, publications traded on the memories of and encounters with the Hell Raiser and Genius Dylan Thomas. That Isherwood never published his reflection on Thomas (until the publication of Diaries, that is, in 1996), adds much weight to the accuracy of it. Many other writers, even those who had always been so opposed to Thomas and his work, were happy to add to his legend.

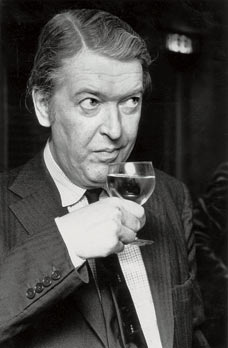

Kingsley Amis, who never quite came to terms with either Thomas’ work or his fame, on news of Thomas’ death wrote to Philip Larkin, ‘I don’t grieve for him as a voice for ever silenced, in fact that part of it is pretty much all right with me.’

That Amis thought this is important because it differs in tone from what he published on the subject, for The Spectator in 1957.

There are two accounts from Amis, a private one and a published one, of his meeting with Dylan Thomas at one of Thomas’ readings at Swansea University when Amis was just 28. The Spectator account is softer, much more sympathetic, although the bare bones of the story remain the same. The Thomas of The Spectator article certainly appears to be a trapped public figure. We are introduced to the Thomas of the tragic myth, he is beleaguered and battered, drunk and isolated, pecked at by a hanger-on, Thomas too ‘good natured’ to ever turn someone away. Amis concludes that, contrary to his own previously held conception, that Thomas’ ‘attitude was the product of nothing more self-aware or self-regarding than shyness.’ Whether true or not, Amis is contributing to the legend of Thomas, as one who moved about us with the black cloud of his own tragic, poetic destiny overhead, a destiny now fulfilled.

In private, Amis was cutting of Thomas’ ‘performance’, it being filled with ‘ragged epigrams topped up with some impressionistic stuff about America… [and] a backlash of dutiful impropriety. And the poems he spoke out with his mouth: ooh corks! He fucked up two of Auden’s things from Another Time… In the pub afterwards, the more intelligent students sneered at him gently, and he perceived this.’ Amis’ prejudice against Thomas’ work informs his rhetoric, just as his awareness of the industry of tragedy informs the tone of his piece for The Spectator; and so the significance of the pieces lies not in the truth of Thomas’ character, but in the rigidity of the construction of his legend.

Of his work, Amis was as damning as he had always been. He once wrote to Larkin, ‘I just wish he’d GROW UP’, and made overt reference to what he saw as Thomas dressing up a trite idea in language designed to prevent people from seeing how trite it is. Whether Amis is right or not about the poem in question (he does not name it in the letter) is perhaps beside the point; what Amis alludes to here is the art of showmanship, of showbiz, of populism.

What Amis claims is that Thomas is not what he is held up to be. Perhaps Amis, in his staunch opposition, saw a central truth to Thomas, even if not for the right reasons. Is it possible that Thomas’ popularity then and now is due in part to the public being wooed by the idea of complexity, the garb of intellectualism, when in fact there is little profound going on? Add to that the fact that Thomas’ legend is attractive in ways that his work is not – the industry of tragedy is and always has been more alluring than the business of poetry, even when the two are bedfellows.

Significantly, what Kingsley Amis identifies as showmanship he does not associate with charlatanism. He explicitly rejects the idea, in private, that Thomas is a fake, but rather, ‘a second rate GK Chesterton… you know: frothing at the mouth with piss.’

It is no wonder that, from all of this, a simple, billboard-friendly, and utterly vaporous idea of the man has emerged; it is Thomas’ own creation after all, one that became so potent it continues to outlive his primary self.

This essay is taken from the collection Encounters with Dylan from the H’mm Foundation.

This piece is part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Dylan Thomas from the Archive.

original illustration by Dean Lewis

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.