What would you do with a naughty daughter? Would you send her to her room and tell her that she would only be allowed to come out again when she has learnt to be nice? Would you refuse her pocket money? Or would you even try to calmly explain to her what was wrong with her behaviour? Now try to imagine what would you do if you had seven troublesome daughters. Whatever your decision, it would probably be not as drastic as that of a ancient Irish king who got so exasperated with his seven wayward daughters that he had them cast adrift alone on the open sea in a boat without a sail. Fortunately for them, they arrived unharmed at the Welsh coast, Cardigan Bay to be more precise, and were taken in by some friendly Welsh families; they married and lived happily ever after. At least this is what the legend of Tresaith wants us to believe. After all, Tresaith means ‘place of seven’.

The origins of the above legend are rather obscure as the Curator of the School of Art Ceramic Collection, Emeritus Professor Moira Vincentelli, confesses during a walk through the exhibition Crossings: Adam Buick and the Legend of Tresaith currently showing in the Ceramic Gallery at the Aberystwyth Arts Centre. It is possible that it was merely invented in the Victorian era to make the seaside town of Tresaith more interesting to tourists. In spite of searches, no one has come up with an earlier origin. The artist Adam Buick had discovered it online after Vincentelli had contacted him in 2016 and asked whether he would be interested in contributing to an exhibition that would have this year’s Visit Wales theme ‘Year of Legend’ at heart. Despite the lack of more information regarding the legend of Tresaith, Buick, Vincentelli and Assistant Curator Louise Chennell agreed that it would make a great topic to be explored from different angles. The curators commissioned three further artists, also living in Wales: Valerie James, Marged Pendrell and Meri Wells. Each of them came up with their very own unique interpretation.![]()

Adam Buick is a ceramicists and conceptual artist who also works with photography and film. Before his training in ceramics, he studied archaeology and anthropology at Lampeter University, 1998-2001. Hence, his aim is to incorporate elements from the landscape into his works. Some of his pots include parts of seaweed; others sand from Welsh shores. The idea evokes pre-industrial times when people were still more involved with and part of nature.

For this exhibition, he created rounded moon jars, which is a traditional Korean form. However, rather than simply creating seven pots, representing the seven sisters, and displaying them in a case, he went much further. In cooperation with Mark Neal of the university’s Computer Science Department, each jar was fitted with a Spot Gen 3 tracker. Buick then travelled to Wicklow at the East Coast of Ireland and launched the vessels into the sea. With the help of the tracking devices, their route could be followed on a website, and Buick filmed and photographed their journey. The result of the project, a 17-minute long film that was first shown in the Arts Centre at the International Ceramics Festival, is surprisingly enjoyable in a very relaxing, almost mesmerising, way. Nothing but the odd curious seagull disturbed the jars’ peaceful bobbing and floating.

Although the sea remained calm, not all pots made it to Wales in one piece; neither did they all arrive in Cardigan Bay as the princesses had. The remains of one jar, for example, had to be collected by Buick from the Isle of Man, another ended up in Cumbria. Two vanished from sight, and just one moon jar was found still intact. All that is left of the seven moon jars is displayed together with photos by Buick and a map that traces their route across the sea. A variety of Buick’s other glazed moon jars are also part of the exhibition. The film can be seen on a loop on a small screen as well.

Valerie James, who lives in Pembrokeshire and studied painting and sculpture at UCW Aberystwyth, has a very different take on the legend. She created two pieces, which she named Myth to Mobile. Each represents a primitive boat with seven figures precariously placed on top. The figures in one boat resemble antique figurines, possibly to remind the observer that the sisters’ adventure happened a very long time ago; however, on the second boat, James installed mobile phone- shaped forms that bear photos of those figurines. Is she trying to transfer the legend from the distant past to the present? Of course, a rickety boat with helpless people is currently a sadly familiar image in the media; refugees from Syria and a variety of African countries take the desperate step of fleeing across the Mediterranean Sea in the hope of a better life in Europe. They give their money to dubious traffickers and must leave their belongings behind. Nevertheless, they try to keep their mobile phones so that they might be able to stay in touch with those loved ones they might have left behind or those who have already taken the perilous journey and are waiting for them on the other side. James’s mobile phones are made of vinyl and Perspex rather than clay, suggesting the transition between the past and present.

Meri Wells, a ceramicist based near Machynlleth who studied fine art and theatre design at Aberystwyth University in the 1980s, also takes up the theme of modern-day refugees. Her large sculpture consists of a series of seven anthropomorphic clay figures, called Walking, waiting, crossing, queuing. Their faces, with features reminiscent of rabbits and sheep, express fear, hopelessness and resignation. Their dignity and individuality has been taken away; they have become part of an anonymous crowd that is herded like animals to the boats. All they can do is wait patiently in line for their turn and pray for the best. The figures of Well’s other group are in porcelain. Smaller and more delicate, they suggest the fragility of life.

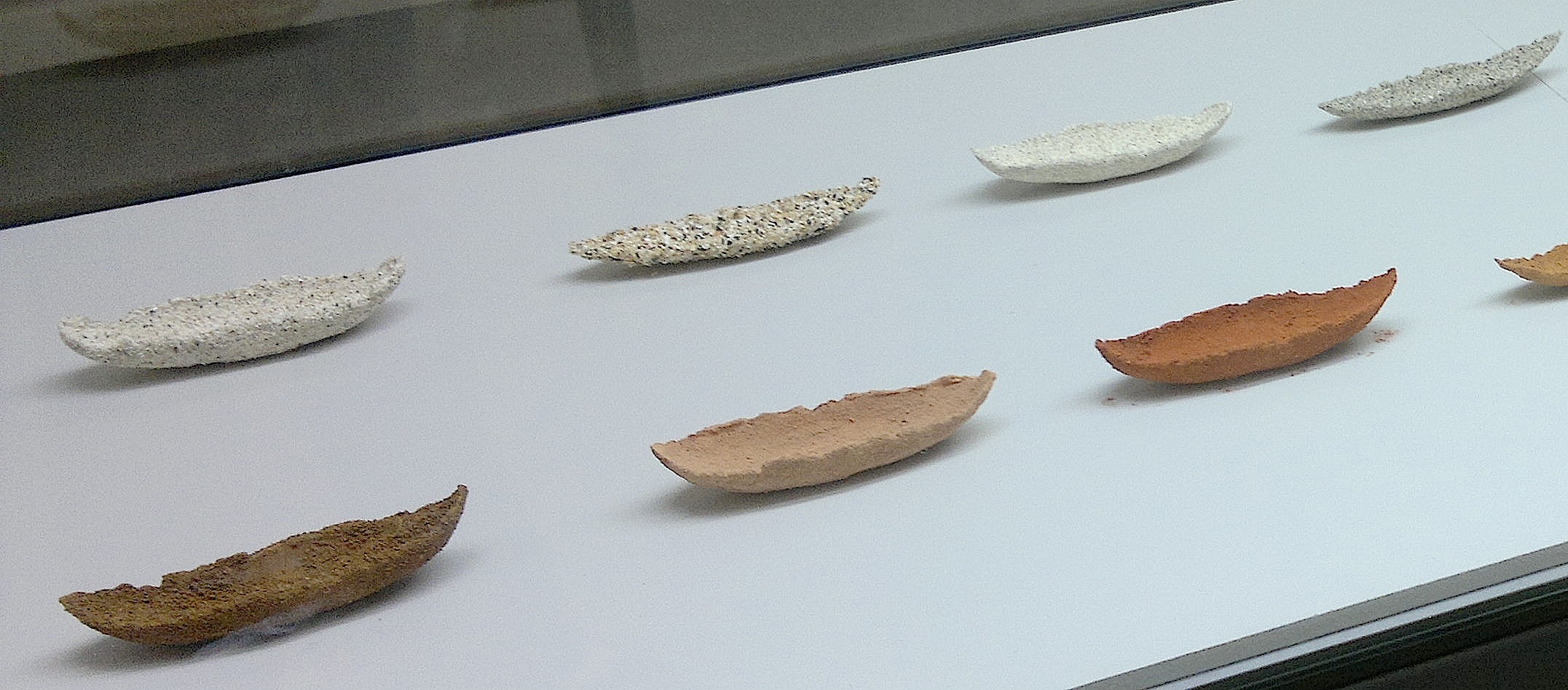

‘Fragile’ is also the expression that comes to mind when looking at Marged Pendrell’s work which she named Crossings. Pendrell lives and works in Snowdonia and trained at Dyfed College of Art and Loughborough University. Like Buick, she is interested in traditions and connections between people and the surrounding landscape. She collected earths and sands from the west of Wales and east of Ireland and produced vessels that would certainly dissolve straight away if set adrift. Some of them would crumble already at the slightest touch. Six of them were cast from a large pebble the artist found on the Welsh shore and take the form of coracles, small traditional Welsh boats. These sand and earth vessels are accompanied by other small boats made from metals such as silver, gold and copper, all materials mined in Wales. They resemble votive ships from the ancient world.

Professor Vincentelli explains that the exhibition is foremost about getting into the spirit of ‘The Year of Legend’. She especially encouraged the use of different media and was pleased about the artists’ responses to the given theme. She hopes that the visitor will engage with the objects and allow their imagination to flow, conjuring up the princesses’ dangerous crossing of the Irish Sea. On the other hand, she alludes to the plight of today’s refugees, who may not find such a happy ending as the king’s troublesome daughters.

This exhibition is on at the Ceramic Gallery at the Aberystwyth Arts Centre until the 27th of August: http://www.ceramics-