Isobel Roach reviews Fannie by Rebecca F. John, a feminist reimagining of the story of Fantine, the tragic character from Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables.

Victor Hugo’s Fantine has had many iterations since her conception in 1862’s Les Misérables; she’s taken to the stage and the screen and sung about her woes in musical form. But Fantine is a woman living in the shadow of men, her story has never quite been her own. Now, in Rebecca F. John’s novel Fannie, Fantine is finally given top billing and a voice with which to tell her own tale. Published by independent Welsh women’s press Honno, John’s skillfully crafted retelling of Fannie’s tragic life is deeply feminist at its core. It’s a short volume, but one absolutely packed full of its heroine’s thoughts, dreams, and desperation as she struggles to earn enough money to buy her daughter’s medicine. After being revealed as an unmarried mother and expelled from her factory job, Fannie sinks lower and lower into a seedy underbelly of crime and poverty – all with an enduring sense of hope that one day, she and her long lost daughter will be reunited once again.

This is a story about the violence and carelessness of men, but John’s masculine characters are shadowy figures that linger on the outskirts of Fannie’s story. Her ‘gentleman’ in particular is little more than a malevolent phantom haunting the memories of his one-time lover. He is faceless and anonymous, described through the intimate details of his body; a reminder of Fannie’s ill-fated sexual daliances. Men by the dockside are similarly lacking in identity, and despite their cruelty and abuse, Fannie’s autonomy and agency are not diminished. She is a heroine that survives men and defies the tragic circumstances of her life, much like the street cat that John uses as a symbolic manifestation of Fannie’s relentless will to go on. Just as the cat ‘slinks and darts’ through the unforgiving streets, so too does Fannie.

More vivid are the women that enter Fannie’s life. From the unjust hatred of the factory supervisor, to the half-hearted sympathy of the landlady, these female characters have presence and identity. The biggest presence of them all is Mother, a madam who takes pity on Fannie and offers her a chance of employment. It’s a bittersweet chance at salvation, but amidst the novel’s relentless misery, Mother’s kindness is a breath of fresh, hopeful air. John uses the book’s cast of prostitutes to explore the roles and labels that are assigned to women by men, whilst simultaneously defying this form of condemning categorisation. The rebel, the lover, and the virgin form a strong community of women, and through their relationship with Fannie, John brings the lives and personalities of sex workers to the foreground.

John’s exploration of nineteenth-century prostitution is emblematic of the novel’s interest in the female body and the wider struggle for bodily autonomy. Our first introduction to Fannie describes the ‘moisture between her legs and under her armpits’; John’s heroine is a real woman whose suffering and experiences are in no way idealised. Instead, she endeavours to rise above her circumstances by retaining a physical sense of elegance and poise; Fannie mimics the movements of a ballerina in order to ‘take back control of the body that was beginning to feel so strange to her’. Fannie’s refusal to shy away from the realities of the body can, at times, be difficult to read. With the shearing of hair, pulling of teeth, spitting out of blood clots, and sexual violence, this is a book that is relentless in its brutal honesty – despite the inner strength and agency of its heroine.

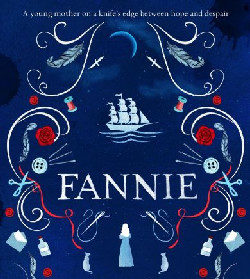

Billed as ‘a story of desperation, but also of love and the soaring power of hope’, Fannie is a novel that juggles these opposing thematic forces with varying degrees of success. John’s talent as a writer is evident in the simple beauty of her prose and the authenticity of Fannie’s voice, yet on occasion the book loses itself in darkness. The hopeful ‘twist’ of the ending feels jarring and incredibly sudden – an extreme departure from the direction the plot had been taking up until the final pages of the book. Yet, despite this, John’s consistent and careful use of nautical imagery (ships and sails caught in the wind) is a poignant and subtle reminder that this is not the Les Misérables we know; this is Fannie’s story and she is at the helm.

Fannie by Rebecca F. John is published by Honno and is available now.