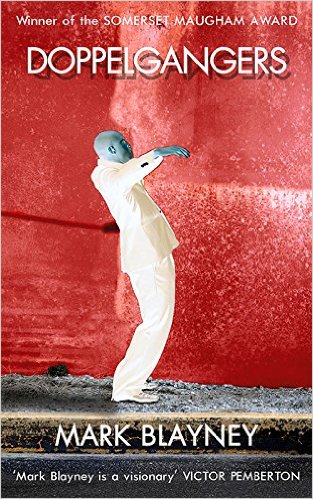

Emma Schofield reviews Doppelgängers by Mark Blayney, a collection of short stories that are equally deceiving and addictive.

Parthian Books

Mark Blayney’s intriguing collection of short stories, Doppelgängers, begins with a story which warns against believing everything we may think we know. ‘The Murder of Dylan Thomas’ features a journalist who tells us that everything we have been told about Dylan Thomas is part of a conspiracy to prevent us finding out the real truth about the poet. The narrator’s convincing voice and attention to detail as he describes his version of reality set the tone for a collection which calls in to question the cloudy line between truth and lies. From this starting point, the Cardiff based writer takes us through a range of different settings, beginning in Swansea before moving on to Spain, with the focus on human nature and relationships remaining constant throughout.

Doppelgangers picks up on some of the themes Mark Blayney drew on for his prize-winning first collection, Two Kinds of Silence, which secured the Somerset Maugham Prize. This new, imaginative collection explores ideas of duplicity in a number of ways, from the confused to the deceitful, as Blayney presents us with an array of characters whose doppelganger, or nemesis, is more often than not themselves and their own struggle to realise what they truly want in life. It is this struggle with the self which causes us to empathise with characters such as the hapless Ella in ‘The Roll of the Sea’, in which a couple grow increasingly separate as ‘he lives inside his own mind, and I live in mine’. Blayney delicately captures these moments of isolation and self-evaluation in this story, making it one of the more absorbing pieces in the collection.

Doppelgangers features a number of stories which have been previously published, such as ‘The Murder of Dylan Thomas’, which was a Seren Short Story of the Month, and ‘Fiesta’, which was first published in Wales Arts Review. These existing stories sit alongside several new narratives, meaning that the structure of the collection as a whole mirrors the idea of the known and unknown. It’s an approach Mark Blayney matches with his writing which focuses on the duplicity and changeability of human nature. Often, in the closing moments of a story, a character we have become familiar with will suddenly do something unexpected or present us with an alternative way of looking at the story we have just read. Overall, this balance is effective, never allowing readers to settle too much into a story before things shift and our perception changes again. When this approach works, such as in the ‘Four Tales from Seville’ sequence, it demonstrates both the fluidity of Blayney’s writing and the complexity of the characters he creates.

This balance is difficult, nonetheless, and at times these sudden shifts and twists in the plot can seem a little abrupt. ‘Success Has Made a Failure of Our Home’ is an amusing story which focuses on the relationship between a couple, Grahame and Lucy Kennard, who happen to meet two strangers who share the same names. The story has a laid back feel as it charts the progress of Grahame and Lucy’s marriage and careers, so it is slightly disconcerting to discover in the final paragraph that Lucy has been having an affair with her husband’s namesake, but apparently intends to choose her husband over her lover. Revelations such as this have a somewhat hurried feel which doesn’t do justice to Mark Blayney’s abilities and mean that some stories have an unfinished feel, as if the narrative has been drawn to close before Blayney intended it to be.

It would also have been good to see more time devoted to the more original and imaginative ideas here, such as the menacing statue in ‘Death and the Maiden’ who becomes the murderous counterpart to her sculptor, slowly morphing into a form of doppelganger which cannot be controlled. At moments such as this the collection is much stronger than when it is revisiting themes which have been explored so many times before. Mark Blayney’s creative mind is at its best when dealing with the seemingly unreal and the struggle for power, rather than when it is constrained by themes such as middle-aged men having affairs, subject matter which seems to limit his considerable ability.

Well worth reading, this is a collection which seeks to disconcert its readers and cause them to question the narratives presented to them. At times it raises more questions than it is able to answer, but it also makes some keen observations about the multiplicity of the human mind. It is an ambitious collection from a versatile author who promises to have plenty more to say and no shortage of stories to tell.