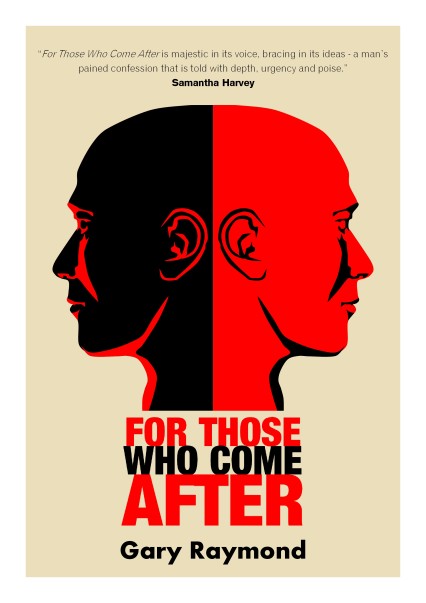

Bethany W. Pope casts a critical eye over Gary Raymond’s debut novel For Those Who Come After.

Gary Raymond‘s For Those Who Come After is an astonishing debut. Presented as a mise en abyme (it’s framed as the memoir of an aged billionaire that is presented to a journalist who is writing the biography of a famous, almost mythological poet) this intensely psychological novel explores questions of identity set against a backdrop composed of intermingled historical realism and archetypal myth. Hal Buren, himself a failed poet, is writing an autobiography of his early life, his brother Piers, and the Name to which his brother’s fate is inextricably tied.

Gary Raymond‘s For Those Who Come After is an astonishing debut. Presented as a mise en abyme (it’s framed as the memoir of an aged billionaire that is presented to a journalist who is writing the biography of a famous, almost mythological poet) this intensely psychological novel explores questions of identity set against a backdrop composed of intermingled historical realism and archetypal myth. Hal Buren, himself a failed poet, is writing an autobiography of his early life, his brother Piers, and the Name to which his brother’s fate is inextricably tied.

The novel spans nearly the whole of the twentieth century, beginning well before the first World War and coming to a close as the millennium nears. In it we are introduced to a host of highly individualized characters; Piers begins as a passionate creature, an aspiring poet who idolizes, beyond all measure, the poet Ki Monroe, though in the beginning his adoration seems harmless enough. Bess, his childhood love, breathes real emotions despite being used by Piers as a screen onto which he projects his adolescent anima. Matilda, the frigid-seeming Buren matriarch comes clad in a layer of icy flesh which reveals itself to be sheathed over hot, romantic bones.

Hal himself is drawn with great sensitivity and delicacy. He is the first billionaire, literary or otherwise, that I have ever enjoyed as a person. Even those who, like Hal’s poor, war-shattered father, only strut the stage for a few brief pages, thrum with undeniable life and verve.

The writing is both carefully considered and beautifully lush. One feels at home in Raymond’s narrative. Attention is paid to the visible world, as well as the (arguably realer) mental spaces the characters inhabit behind the bones of their skulls. Because so much of the action takes place in their heads, looking out through those sockets, we are party to a tremendous amount of projection. Part of the fun of this novel involves picking apart the warp of what the characters are described as seeing from the the weft of what really exists in their world. Here’s a small sample of this trick in action. Bess and Piers have gone to a coffee house known for harboring writers. Bess is looking for any poets that Piers might have read:

Bess looked on his behalf. A man with a bowed head, he was examining a newspaper, his brow in his palm, a cigarette pushing a twirl of smoke from his head. He looked sad, stuck with sadness, tied to it. He could be a writer, thought Bess. On the next table was a couple, young, but older than herself and Piers. The woman was wrapped up tight, smiling, touching the man often on the forearm; they spoke but looked past each other, looked into some distant philosophical notion of love, no doubt.

Speaking of love, philosophical or sudden and romantic, there is a lot of it in this book. According to Carl Jung, love at first sight is often a form of self-love. The love-object seems to reflect internal qualities that the lover either has, or wishes that they possess. This kind of love comes on like a storm, it brings a lot of tumult, a lot of passion, and it tends to fade very fast; as soon as the love-object reveals themselves as a whole, complete person with traits that don’t mesh with the lover’s ideal. Characters in this book enact this process in a real, and devastating way.

Piers, for example, falls in love like this twice: once, in adolescence when he becomes enamored with Bess (whose physical description matches one common depiction of the archetypal anima) and once with the poet Ki Monroe, who becomes an avatar first of Piers’ unknown father, then as a living version of the thing which Piers would like to think of as the ideal version of himself. In this, Raymond’s writing reminded me of the novels of Robertson Davies, infused with the unflinching, grounded violence of Ann-Marie MacDonald.

The central question, for the reader, is ‘who is Piers Buren, and why should we care about his connection to this fictional famous man?’ The answer lies in the blood and thunder of war-ruined Europe, and in the extremities of hero-worship, which can form a very special type of madness. This is a novel of love, and obsession; filial love, and insanity of a very poetic sort.

For Those Who Come After is available from Parthian Books.

Bethany W. Pope is a writer of fiction and poetry and a contributor for Wales Arts Review.