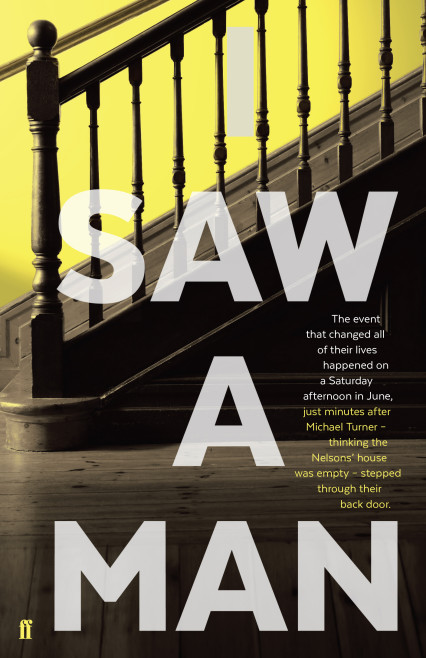

I Saw a Man is a fiction novel by Owen Sheers which keep death and pain at its core for a thoughtful and arguably difficult read.

We cannot avoid labels and categorisation, but they trip us up at every turn. I Saw A Man is Owen Sheers’ second novel, but he is much more than a “novelist”. He describes himself as “poet, author and playwright”, and I like his putting the term “poet” first. The way in which he writes, be it in the form of a poem, play or novel, has a particular quality of grace, beauty and ease which can be called “poetic” and helps to make sense of otherwise senseless things. Big things like death and pain.

Death and pain are at the heart of I Saw A Man, but, ultimately, this is a book about how people carry on living anyway, about the ways in which we try to save ourselves. The author sums up the purpose of it as he describes people gathering in the evening light on the edge of Hampstead Heath:

Life, in the final moments of the day, had been coaxed to the surface in all its complex, simple beauty. As if to say, through the coming hours of darkness, do not forget this. This is what you wait for, what you work for, what you love for.

At the start of the novel, Michael Turner has moved to London, to a flat on the edge of the Heath, after the death of his wife, and formed friendships with his neighbours, Samantha and Josh Nelson, and their two young daughters. This is the setting for everything that happens from the hot summer’s afternoon when Michael steps through the open back door of the Nelsons’ house in search of a small screwdriver which he has lent them a couple of days previously. But while things flow from what happens in the house, that flow has started long before, from the time before Michael’s wife Caroline was killed, and is affected by that and also by the lives of people many thousands of miles away.

Caroline, a journalist, was killed in a US drone strike in Pakistan. As Caroline’s colleague Peter arrives at the cottage on the Welsh borders where she had lived with Michael, the River Severn is “flashing in the distance like a falling coin”, an image that pre-figures the news which Peter brings. Owen Sheers does not prettify or glorify her death; he is factual. When Josh, who works for Lehman Brothers in the City of London, is complaining to Michael about being “‘fucking exposed with my balls on the wire’” in his work, Michael wants to tell him about Lehman’s investment in the manufacture of the Hellfire missile which killed his wife:

How Caroline, in doing her job, had also been ‘fucking exposed’, sitting as she had been at the brilliant centre of that Hellfire’s 5,000-degree thermobaric blast. How, at that heat, flesh melts instantly, bone is vaporised and the person you love goes, in less than a second, from being to not.

As in real life, several strands go on in parallel in the novel. For what seems like an unconscionable length of time, although it is only minutes, Michael is gradually making his way into the Nelsons’ house. Chapter after chapter opens with this, screwing up the suspense so that when the moment arrived I actually gasped.

Interspersed with this are the backstories of the main characters and, also, the story of Major Daniel McCullen, the man who flew – remotely but he nonetheless flew it – the Predator from which the missile that killed Caroline was fired. In the last few seconds when it is too late to abort the deployment of the missiles, he sees something on his monitor which will haunt and torment him.

The target of the missile was not Caroline. In that sense, it was an accident that she was killed. No one willed her death. There is another accident in this novel. Something happens which no one will, but which different people’s actions either brought about or could not prevent. There are inevitable “what if?” questions for the people involved and affected. I Saw A Man explores the nature of the accident and the related issues of agency, connection, inevitability and choice. As Michael was to tell himself after it all:

None of their choices had been malign. And yet, combined, they’d created darkness more than light.

Owen Sheers writes about all this with a light touch – his novel is much more than a conventional thriller but it has the pace and atmosphere of one so that you are driven to consume it like a lion devouring its prey and then let it sit with you for some time as you digest it. One thing that emerges on contemplating the story is the realisation that the novel is written with a Droste effect – a picture inside the same picture as on the Droste cocoa tin. We learn of Michael’s work as a writer who immerses himself in the lives of his subjects and then removes himself from the scene to complete the work. In his desire to save himself and do more harm than good in the impossible situation in which he finds himself in his own life, he tries to do the same thing, to “change the day’s truth”, by pretending he was never in the house when the event occurred on that June day.

Daniel, the US drone pilot, also living with an unbearable truth, does the opposite though. He writes to Michael because:

He was tired of being unseen. Of being dislocated from his actions. Of witnessing but never being witnessed. He wanted to own his life, and he knew that meant owning all of it.

And as corresponding with Michael maybe Daniel’s salvation, or at least the way he can move on, so writing may, in the end, be the way Michael can “bring it to a close for all of them.”

For me, a good novel is one which carries me with it on the crest of its writing but which, when I am back on the firm land of the shore, leaves me with food for thought. I Saw A Man does both. It deals with issues of our time and timeless issues too. Excellently achieved.

I Saw a Man by Owen Sheers is available now.

Cath Barton is a regular contributor at Wales Arts Review.

For other articles included in this collection, go here.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.