In a new series for 2019, Wales Arts Review will be asking what are the greatest albums ever produced by Welsh musical artists? A wide selection of writers will be examining their favourites, and here Gary Raymond looks at one of the most influential albums to ever come out of Wales, Young Marble Giants’ Colossal Youth.

The album comes out of nowhere; an ambiguous, modest wheeze of synthesised effects, barely registering; and thirty-eight minutes later it fffts and purrs, a nervously prodded organ seems to disassemble before you, and the album’s over, and you’re left wondering what exactly just happened. Nothing sounds like Colossal Youth. It has its kin – I could list many albums that remind me of it – Nico’s The Marble Index (1969), Skip Spence’s Oar (1969)– but these records don’t sound like Colossal Youth, they merely seem to inhabit the same space; most likely an empty dilapidated old picture house with fallen gantry and ripped up ruby-coloured upholstery.

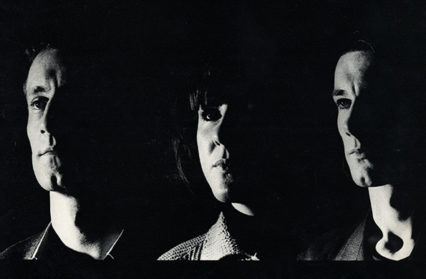

Released by Cardiff trio Young Marble Giants in 1980, Colossal Youth is perhaps the great time (and simultaneously timeless) capsule of the turn of one remarkable decade into the next. What the seventies will be remembered for, musically, is punk, and what the eighties will be remembered for is the electronica of the synthesiser. Where Colossal Youth sits is at this right angle where the three-chord gob of punk and the earnest shoulder swaying of New Romanticism is exactly at its most interesting point. It is a deconstructionist masterpiece, in that it does exactly what Howard Devoto could never really bring himself to do with Magazine, and that is: lay bare.

The music on Colossal Youth would surely have been mistaken for a demo by any other record label execs had YMB not been signed to Rough Trade, where they shared a stable with other creatives who sounded like nobody else (think of The Smiths’ début, Scritti Politti’s ‘Skank Bloc Bologna’ (1978), and Ivor Cutler’s Privilege (1983), and you begin to get an idea of Rough Trade’s philosophy in the early 1980s). That the music sounds so incomplete is only part of the charm. There is much being done in the empty spaces. It is folk music, of course, only the folk of the basement night club with sweat-dripping walls, leather and denim, acne, bubble gum, and monochrome nights where nothing quite goes to plan. Alison Statton’s vocal is pure flat-folk, in the tradition of the fifties’ London coffee dens. There are little inflexion and no passion, and it is captivating, palely sitting atop the intricately assembled songs like a barefoot chanteuse, legs tucked under the bottom, on a Moroccan rug.

And these songs are not composed, not ‘played’ like the Buzzcocks might have recorded them, but they are assembled. They are put together like Lego blocks, or stickle brick, every inch clicked into place, carefully, but far from delicately. These songs are robust. Anything less sturdy would not have lasted so long, so well. Kurt Cobain took more from the Moxham Brothers’ songs than he ever did from the Sex Pistols, and he readily admitted it.

So, the songs. To the uninitiated, I envy you the chamber of two-minute classics Colossal Youth has waiting for you. The first time you hear the bassline of ‘Wurlitzer Jukebox’ you will begin to wonder if you have ever really understood the skeleton of funk before, and you will understand why Kraftwerk was one of the funkiest bands to come out of the 1970s. ‘Include Me Out’ is exactly something the New York Dolls might have gnarled right up, and then in comes a Muddy Waters slide riff from Stuart Moxham, and we are in the realms of purity that would not be heard again until Mark Hollis’ Talk Talk masterpiece of modern roots music, Spirit of Eden (1988), some eight years later. The songs on Colossal Youth are some of the richest ever collated to one album.

There is a real tragedy on this record, made all the more supple for the blips and clicks of the rhythmic canvas, the soulless delivery of the musicians, and the corpuscular presence of Statton above it all. ‘Eating Noddemix’ is like a Raymond Carver short story, not lyrically, but spiritually. And yet there is the touch of Debbie Harry in the way Statton strides across the spoken word middle eight. And there is the sinister edge, the Corman-Esque emptiness of some of those organ riffs, such as on the masterfully unsettling ‘N.I.T.A.’, in which Statton sings an almost plaintiff-sounding love song that is, frankly, bloodied with menace. The revelation toward the end of the song’s fourteen lines (that the narrator is a mother, and so could be singing to her flit offspring) gets nailed to the door, rather like Piper Laurie in Carrie.

There is a lot of fun to be had here, too; an important ingredient for any Great album. The Moxham brothers, Stuart and Philip (Stuart, the guitarist and keyboard player, writes most of the songs; Philip providing the distinctive compressed bass and the percussive tapestry) like their musical tricks, allusions, and pranks. They switch from funk to Poe-facades with a wink of the eye, and they slide from Chuck Berry chord progressions to Kurt Weill tumults with just as much dexterity, all done with a wry smile, even if it’s only on the inside. The carnival is never far away from Colossal Youth. Manning other stalls you’ll find Ennio Morricone, Jeff Beck, Neu!, all flower-pressed into this concise, pure soundscape.

But the listener is never allowed to forget that Young Marble Giants’ Colossal Youth is a reserved record, a suppressed expression, although not a muted one. It is brimming with the punk idiom, with the disenchantment, the snarl, and the vestments of Eddie Cochrane.

Tracks like ‘Salad Days’, ‘Brand – New – Life’ and ‘Credit in a Straight World’ (covered brilliantly by Hole – a song that sounds almost written for Courtney Love, and perhaps the greatest East Coast MTV grunge-pop record of all time) are towering classics of form, melody and assembly. If my personal favourite, ‘Wurlitzer Jukebox’, is partially deep in my soul because the refrain can be perfectly replaced by ‘Murenger Jukebox’ (the late lamented and legendary jukebox from my local pub), it is also there because it is as close to pop perfection as you are likely to ever come across.

In 2007 Young Marble Giants reformed for a one-off gig at Clyro Court in Hay-on-Wye as part of the festival. Even though they have played a handful of reunion gigs around the UK in the years since, at the time it was a point of pilgrimage for many. I walked an hour in the rain through country lanes to get to the gig and then stood in the peculiar school-hall atmosphere of Clyro Court, sopping wet, drinking cans of Red Stripe listening to the three band members clip through Colossal Youth and a few other b-sides and EP tracks that make up their entire oeuvre. It was as close to the perfect synthesis of music and atmosphere that you are ever likely to get – just inches from the empty dilapidated old picture house where I always picture YMG playing in my head whenever I play the record. After the show, I did something I have never done at any other gig in my life ever: I approached the artists. I went up to Stuart Moxham, who was unplugging his effects pedals on the stage, and I told him I thought Colossal Youth was a great album, and I thanked him for it. He thanked me in return and shook my hand. And I went back into the rain.

Colossal Youth by Glass Marble Giants is available here.

Gary Raymond is an editor and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

For other articles included in this collection, go here: The Greatest Welsh Album

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.