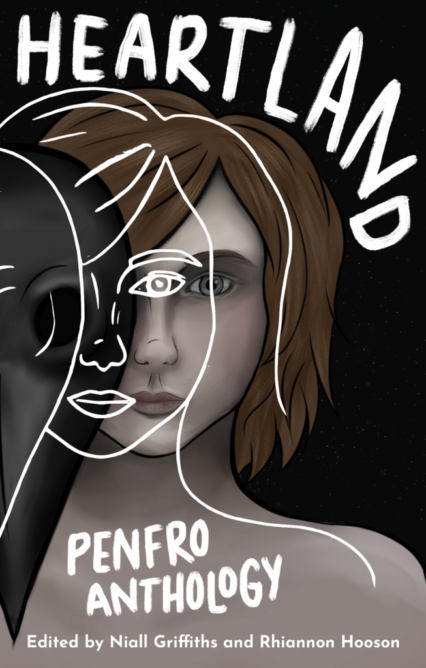

Nigel Jarrett reviews the latest Penfro Writing Competition’s anthology of finalists and winners from the annual Terry Hetherington Prize.

In a self-mocking moment of despondency, Welsh writer Leonora Brito said everyone around her seemed to be writing; they also appeared to be entering literary competitions and winning prizes (her own persistence was rewarded). The poet Fleur Adcock said she avoided competitions because ‘I don’t want to be placed 57th’.* Both probably felt that what they had to say – Brito in her colourful stories about Tiger Bay, Cardiff – might be stampeded out of contention.

The annual Penfro Book Festival runs a writing competition for poetry and short fiction. Although it’s open to everyone, just over half the writers in this anthology of the 2019 finalists are Welsh or have connections with Wales; it could be more, where biographies are not specific. That possibly reflects how widely the competition was advertised and promoted and whether or not writers outside Wales, far-flung or other, considered it profitable to enter. Maybe the trawl was capacious and the Welsh triumphed, as is often the case.

There were 32 finalists, one of them good enough to have a couple of entries make the judicial cut. In her report, the poetry judge, Rhiannon Hooson, says patterns emerged as she read the entries: grief private and personal; past and present; time’s passing; metaphorical burial and disinterment; – that sort of thing. Her list seems more variable than thematic, and even more typical of the range of subject-matter normally uncovered by competitions of this sort. In one sense, the only common theme, perfectly honourable, is the writer’s hope of winning.

There were 32 finalists, one of them good enough to have a couple of entries make the judicial cut. In her report, the poetry judge, Rhiannon Hooson, says patterns emerged as she read the entries: grief private and personal; past and present; time’s passing; metaphorical burial and disinterment; – that sort of thing. Her list seems more variable than thematic, and even more typical of the range of subject-matter normally uncovered by competitions of this sort. In one sense, the only common theme, perfectly honourable, is the writer’s hope of winning.

Niall Griffiths, the fiction judge, admits to having read ‘urgent explorations of human essentials’ and about the ‘fears and desires and losses and pains which inspired our earliest-recorded story-tellers.’ The stories proved that their authors were ‘driven to write, to grapple with the fundamentals of being human.’ Hooson was impressed by ‘the technical proficiency with emotional honesty’ of the poems that stayed with her.

These claims might be considered fulsome even for an anthology of work by writers whose names were known, never mind mostly unknown ones driven by the desire to come first. Moreover, one need not be cynical to suggest a relationship between a writing competition and the agreed publication of a book of its winning entries. It puts a lot of pressure on the judges – I know: I’ve been one – to think the best of what could easily turn out to be a dud crop, from which winners would still have to be chosen. It’s why many believe the comparisons engendered by these gladiatorial rushes to be odious. That the appraisals of Hooson and Griffiths are honest, however, goes without saying; indeed, it’s a recommendation of the work and the collection. At the same time, most winners of literary contests – I’ve been one of those, too – know that the merit of their work, ipso facto superior, is of the moment and in the gift of just one or two individuals: different judges, different decisions perhaps.

Be all that lengthily as it may. This is not the place to endorse adjudication or to question it. There’d be little point. Although the analogy shouldn’t be pushed, these are runners and riders, each rider wearing its unique livery. That there are winners – Elizabeth Wilson Davies for poetry and Richard Owain Roberts for short fiction – must be noted; that the liveries are distinctive, if not all equally so, is worth observing. Another observation might be that humour seems to have flown from short fiction and detail from poetry. Ditto politics. The first re-appears in Ben Wildsmith’s hilarious Table For One, in which a sold-out artist dines with his former self, he of the ‘petrified defiance, hollow pride, and retreat from reason’. The story is ultimately tragi-comic, and that’s a gear shift upwards. It’s there too in Estelle Birdy’s Vaj-Nut Hut, which has two single mums devising an outrageous business scheme involving doughnuts and the female nether regions. Like Wildsmith’s, her story has a serious undertow.

Detail returns as a dazzling scatter throughout Philip Dunn’s poem Ministry of Labour, A Dictionary of Occupational Terms, based on an eponymous tome bought at a car boot sale. It celebrates particularity: ‘For dyke-reeve, it’s singular; stemmer of floods./His Dutch paragon, a dyke-mayor no less,/Sat for Rembrandt: Dirk van Os 111, at seventy.’ Dirk the Dyke, among ‘a foolscap slab of 30,000 terms’. This is poetry that’s banished the confessional, and much of it here is also joyously descriptive, as in Rosalind Hudis’s By-the-wind Sailors, a meditation on the jellyfish-like Hydrozoan Vellela vellela, a name that sounds ‘like a lament from places unsafe to travel’; Ian Murray’s Sorting Office, in which the poet’s view of dereliction allows him to look beneath and beyond the surface; and Anthony Watts’s Lord of Carrion, or vulture, which, in its concluded anticipation of death by predator, is ‘a collapsed umbrella’.

Poems don’t have to be crammed with enumerated particulars. Where they aren’t in this anthology there’s a compensatory flight to the exotic or the past as well as an absence of navel-gazing. Darren J. Beaney’s graphic Sugarland might pictorially be straight out of Edward Burra – ‘hard boiled sweat and pornographic scent’ – and it may be no coincidence that at time of writing Beaney was studying at the University of Brighton: the poem is redolent of the Brightonesque. Kittie Belltree’s Self-portrait with Onion is an exquisite musing on sorrow; David J. Costello’s Furnaceman a spare portrait of occupational hazard and the distress it causes; and Derek Sellen’s Green a marvellous testimony to verdure: ‘the promiscuity of ivy and bindweed’; the green that ‘prowled abandoned temples and ate fallen cities.’

After Iconoclasm: The Jesse Tree Window, by Angela Graham, reaches back through the agency of the 16th-century, multi-faceted stained glass at St. Dyfnog’s in Denbighshire to the Christian story and its triumph over misrule. Jane Burn’s The Sound of Death in a Soft Mouth is ventriloquism, talking animals notwithstanding, of mortality in the natural world, specifically one skewed by humans: ‘I have held the dream of fields inside my cheap meat’. In Cinnamon Girl (After marginalia by Dr John Dee in his copy of Gesner’s De Remediis Secretis), by Mary Anne Smith, the particulars are in the title, the delight in the closely-encountered drawing by the doctor of a girl next to a remedy for healthy skin. It involved distilling the titular spice and other ingredients, its result ‘then splashed upon the face like the first rain in May’.

Narrative is largely given over to the stories. There’s little engagement in these poems with society in the mass. More’s the pity. Both are conjoined in Maeve Henry’s Alterations: a red cocktail dress is being collected from a Kurdish tailor and his compatriot employees, who ‘have a country yet not a country’ and are in Britain for a better life. It reminds the poet’s partner of a dressing-gown worn ‘about the time NatWest became a Costa/about the time the twin towers crashed down’. A latte is real, a disaster 3,000 miles away an albeit shocking image on a TV screen. It’s not as though form has over-ridden political or social content, or any other subject for that matter. Henry’s poem is cast in couplets – a structure that suits its flow – but Selma Carvalho’s Sudden Midlife Storms is fractured and reflects an admirable attempt to convey the contortion of a relationship at a T-junction.

Family or some sort of domestic life is probably the anthology’s most common theme. Kathy Miles was the only competitor with two entries in the final. Angelology and Summoning are poems in which a father and mother are vividly recalled in examples of the disinterment Rhiannon Hooson mentions. Julie Ann Rees’s story The Islanders features a protagonist whose unspecified anxiety or illness leads to a vision of horror on a remote island; an individual from a broken family lost among the rest of humanity and imagining the worst of it. There’s probably a political dimension to The Puppet Mistress, by Rebecca Trick-Walker, if only one could locate its encampment, in which children, with the aid of puppets, are shown the possibility of family reconstruction.

Loss of a parent is chronicled in Steve Wade’s Beneath a Sky, Kingfisher Blue: a boy recalls the farm death of his father and the trauma and uncertainty it engenders. The grand-daughter who has suffered loss in Karen Hill’s poem The Art of Plaiting Hair cannot bear the thought of her grandmother’s death from cancer, foretold by ‘the black spots on her liver’. The ‘hunting prints and pious needlework’ on the walls of a Valleys café in David McVey’s story Everything Pie look down on a narrator whose meal evokes some unpleasant family recollections. The couple moving to Wales in Diana Powell’s Dead Sheep/Babies discover reminders of the trauma they are leaving behind and the impossibility of accommodating it in new pastures. And so on.

It’s a relief to be taken to an iron-ore mine in Australia, where the Antipodeans nonetheless have similar concerns. Another one Bites the Dust, a story by Kelly Van Nelson, tells of the contracted site-safety manager Miles, who’s a long way from the home he supports and is living among the workforce in conditions of deepening and disturbing rancour. Then there’s the journey into myth mapped by Eluned Gramich in her story Cream Horns, which has a super opening: ‘The death began on Sunday. It was finished by Wednesday.’ A woman struggling with miscarriage-type events seeks the help of a Gwalian Mrs Cravat (the narrator was expecting someone akin to Morgan LeFay), who lives beside the location of a Mabinogion story involving rape and the birth of twins. The outcome is as hazy as the narrator’s drug-induced vision is impalpable.

All this tribulation has much to do with identity, the subject of Moira Ashley’s ‘concrete’ poem Double Helix, a lyrical exploration of origins that include ‘Jamaica’s cassonade sands’, and Kathryn Tann’s story Blushing Rainwater, a lovely portrait of self-consciousness. The no-nonsense quatrains of Phil Jones’s poem Your Father’s Father had Eyes like Yours seem fit vehicles for its focus on masculinity. Persona, particularly the distaff, is foregrounded in Morgan Davies’s story The Tenant Joneses, in which a trio of women representing three fibrous generations of a rural Welsh family find themselves fielding the attentions of men who believe that without them they are less than self-sufficient. Home-making by the couple in Ellen Davies’s poem DIY is confounded by a dysfunction that bodes ill, the poem’s title being both metaphor and message. Perhaps it’s no bad thing that the anthology ends with Christina Thatcher’s poem Touring Tenby with the Man I will One Day Marry. It’s a tour that has taken in a chequered past, historical and personal, beside which the present is intimate and unshakeable. Nice to end on a solid note.

That leaves the winners: Elizabeth Wilson Davies’s poem, Heartland, is a bleak intimation of mortality in a Wales still defined by decline and dereliction and the ghosts of times past. The last are represented by antique family names on gravestones: Titus, Waldo, Seth, Theophilus, Zorabel. They will soon be joined by the narrator’s partner, who is ‘present and not present’, for ‘the writing on the stone stops/halfway/down.’ Anyone brought up in a Wales defined by images of a stubbornly insistent history will recognise the picture. It’s as if the past shifts the landscape in its claim on the will of a generation wanting to re-make the land in its own image. Heartland is a powerful statement.

Richard Owain Roberts’s winning story, Terrence Malick, is named after the controversial auteur, just the kind of person who may have popped up in the interview being conducted flittingly, inconclusively (Roberts will like the yoked adverbs) with the writer-narrator on route to a literary event in Serbia. It’s a story like no other in the anthology – fresh, fugitive, dreamlike, yet one in which the writer is in complete control of the aesthetic. Roberts’s reputation for being elusive is a tad risible. But he’s an important new voice in fiction, not just in Wales. No question.

The foregoing is not a critical review but a commendation and survey of work that has already undergone assessment – i.e., it’s not a critique of the works themselves or a qualitative comparison of one finalist with another. Despite its challenges, often hopeless of positive outcome, there’s not much formal experiment in the anthology; but such a statement would be a bit rich coming from someone who stuck to norms. The range of subjects and the confidence of addressing them in both poetry and prose must have impressed the judges, because they are impressive. Let’s leave it at that.

* Quoted in How To Publish Your Poetry, by Peter Finch (Allison and Busby).

Heartland: Penfro Anthology, edited by Carly Holmes is available from Parthian Books.

Nigel Jarrett is a former daily-newspaperman. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize and the Templar Shorts award for short stories, and is represented in the Library of Wales’s anthology of 20th–and 21st-century short fiction. He’s also written a poetry collection, a novel, and two volumes of stories. Among others, he writes for Acumen poetry magazine, Jazz Journal, and on music and other subjects for the Wales Arts Review. His pamphlet of stories, A Gloucester Trilogy, has just been published by Templar Press.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.