In an exclusive extract from a new evaluation of the artist, Peter Wakelin explores the profound effects of Capel-y-ffin on the genius of modernist David Jones as a new exhibition of Jones’ work opens to run over the summer at y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, in Brecon.

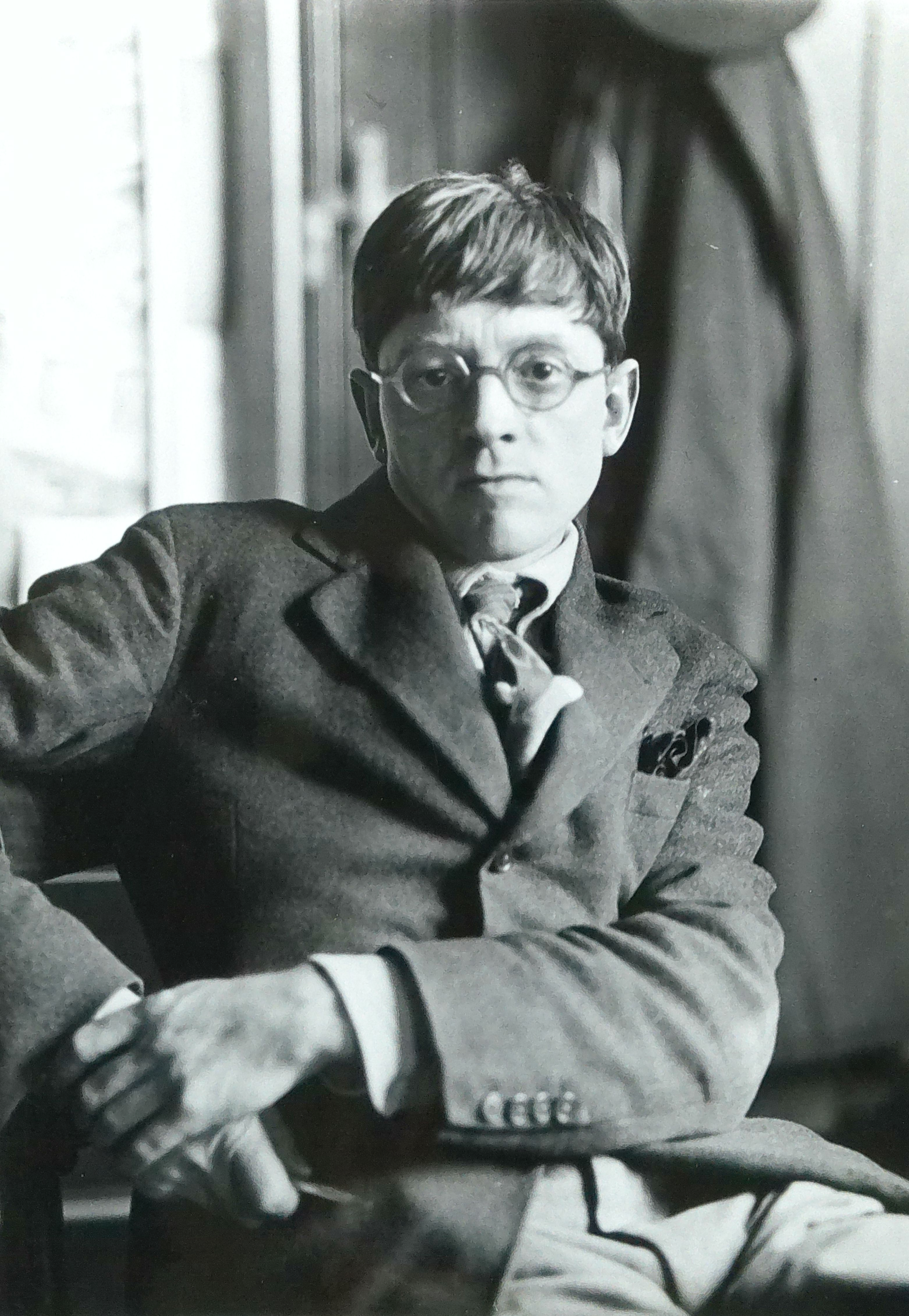

Intense experiences of new places can be turning points in the creative lives of artists. David Jones identified his periods living and working at Capel-y-ffin in the mid-1920s as ‘a new beginning’: ‘My subsequent work can, I think, be truthfully said to hinge on that period.’ His experiences comprised both revelation and inspiration. So sure was he of his new direction that when he went home he burned almost all his earlier paintings. Though his work continued to change and develop thereafter, Capel persisted in his visual and poetic imagination for the rest of his life.

The experience of place was especially fertile for British artists who were drawn to the mood of neo-romanticism between the early 1930s and the early 1950s. Like Jones, they cross-fertilised the innovations of modernism with an appreciation of landscape’s associations and evocations, taking a step away from the purely formal, visual values that had predominated in the era of Post-Impressionism. One of neo-romanticism’s preoccupations was with genius loci or spirit of place. From the beginning of his Capel years, Jones can be seen as a precursor to this movement – perhaps a pioneer. His sense of nature as sacrament and sign emerged explicitly in paintings such as Sanctus Christus de Capel-y-ffin and implicitly in many others. It was expounded later in poems such as ‘The Tutelar of the Place’ and ‘The Sleeping Lord’.

Diverse artists of Jones’s era found encountering a new place to be an impetus to creative reinvention, among them Graham Sutherland and Barbara Hepworth. Sutherland wrote that the jagged ancient landscape around St Davids in Pembrokeshire, which he first visited in 1934, had ‘taught’ him to paint: ‘From the first moment I set foot in Wales I was obsessed’. Hepworth’s sculpture shifted after she moved to St Ives in Cornwall in 1939 from geometrical abstraction towards rhythms observed in rocks and waves.

In many cases, new experience of place has been accompanied by meetings of new minds. In Cornwall, Hepworth and her husband Ben Nicholson came into daily contact with a stimulating artistic community that included the émigré Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo. In an earlier generation, the crescendo in Van Gogh’s painting after he arrived in Arles was driven by fresh landscapes and southern light but also by his debates with Gauguin. For David Jones, Capel-y-ffin brought rich exchanges about art and its purposes among a remarkable resident community and a flow of visitors. Looking back, he made the point that a change of place or subject matter cannot be the driving force for advances in an artist’s work unless accompanied by ‘new or more developed perception relating to the formal problems’.

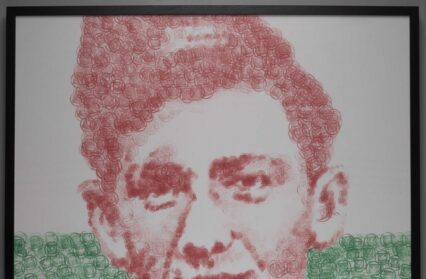

David Jones was 29 when he arrived at Capel but after years of art training and then service in the First World War (the ‘parenthesis’ as he called it), he had not yet found his direction as an artist. The next four years transformed him from an uncertain student into a noted modernist and a leading illustrator. Within a decade Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery, could describe Jones as ‘the most gifted of all the younger English painters’. After his epic poem of the First World War was published in 1937 Jones was called a genius by, among others, T. S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky.

He is not always easy to appreciate. The delicacy and ‘objectness’ of his watercolours is best seen in the originals yet conservation demands that they are not often on display. The length and narrative arc of his poetry usually defeats anthologists. His Capel period is his most accessible, but even then, before his writing and painting accumulated extra layers of complexity, his work was sometimes characterised as difficult. His first dealer, Arthur Howell, who came from Cardiff and sought to promote new art from Wales, would play a trick on visiting critics by surreptitiously leaving paintings leaning up against the wall for them to see on multiple occasions until their initial incomprehension was overcome. Another observer advised in 1927: ‘His exaggerated simplicity seems to repel at first, but I think all his detractors will have to admit themselves in error.’

Some audiences missed the point. He had his share of bad reviews, and later detractors too. The art historian Malcolm Yorke wrote in 1988 of his work as ‘arcane, fey and idiosyncratic’. As John Petts wrote for the Arts Council retrospective of 1954: ‘Works of art which are by their nature subjective, intimate and transcendental, are sometimes condemned by those who have not learned to read them.’ Any viewer must take time to look closely to grasp the real richness of Jones’s work. Those who do, not just in Britain but internationally, hold him in exceptionally high regard.

It is probably true that Jones has had more recognition in Wales than elsewhere: major public exhibitions were held in his lifetime and extracts quarried from his epics have appeared in anthologies of Welsh verse. In 2016, Welsh National Opera adapted In Parenthesis for the stage. Even so, 2023 sees the first major presentation of his work in Wales since his centenary in 1995. I hope it will be an opportunity for new audiences to discover David Jones and for those who know him well to enjoy his brilliance afresh.

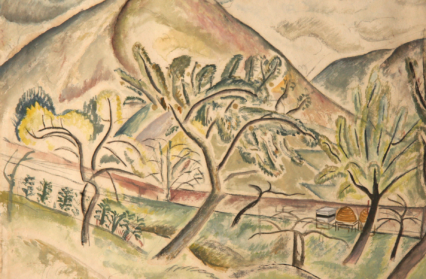

From the moment he arrived at Capel-y-ffin, David Jones was set challenges by the landscape. Its enclosing mountains were quite unlike the places where he had worked previously, and he felt the different history of the borderlands. He could not frame a traditional landscape composition with such high horizons. Even the Welsh father of British landscape painting, Richard Wilson, had stepped back from mountains to depict them. Here, the subject was close; it rose up to fill the view. When Eric Ravilious came to paint at Capel a decade later he joked: ‘the hills are so massive it is difficult to leave room for them on the paper.’

Jones started painting outdoors during that first Christmas, working quickly in the cold. In possibly his first picture, Tir-y-Blaenau, he seems to have chosen the mountain on the east side of Capel rather than the one that would prove to be his favourite, but he hit almost immediately on the way forward. It was a breakthrough that freed him from the polite organisation of his previous landscapes. Jones would never part with the picture, hanging it over his bed. He said it was the one from which all his ‘subsequent watercolour thing … developed.’

Tir-y-Blaenau displays precisely the ‘strong hill-rhythms and the bright counter-rhythms’ of the river that Jones talked about later, the convex arcs of the mountain and the field below it mirroring the concaves of the two riverbanks. The right side seems to be spinning away, the trees growing at right-angles to the slopes, but the composition is stilled by the standing horses and bound together by wattle fences and spreading branches. He gives more-or-less equal tones to the far summit and the foreground river, compressing distance. The intersecting arcs imply and underlying circle. Jones wrote later: ‘it is an abstract quality, however hidden or devious, which determines the real worth of any work.’ The hill, field and river also suggest an anthropomorphic sensibility, relating the landscape to the human figure, which he would pursue decades later in his poem ‘The Sleeping Lord’.

Tir-y-Blaenau was a breakthrough in technique too. He said he needed to be outdoors to capture the tensions that made for a ‘live’ painting, whereas working from memory produced easy lines and boring rhythms. Working in all weathers made him work fast. He used crayon and ink fluidly and sparingly and watercolour translucently so that the white of the paper lends the whole a mid-tone that was to characterise almost all his work from this date onwards. He enjoyed watercolour’s transparency, which permitted images to overlay one another – an equivalent of experiencing the world, where attention shifts and vision persists. As David Blamires wrote:

He quickly developed an idiosyncratic use of pale colours, applying them discontinuously in dabs and strokes, so that the effect is almost disconcertingly vibrant. One never feels that a scene has been captured in the timeless still, but rather that it is still moving, that the water is rushing on, the trees are swaying in the breeze and the light is just changing.

The paleness and tentativeness was a great change from his recent work. It was perhaps expressing a feeling that as he saw more, he knew less. The mastery he was to develop shows in Bridge over Honddu of 1926, one of several painting of the footbridge and ford on the Nant Bwch (little changed today). Trees dance in the intimate valley, which is contrasted with the bare top of Darren Lwyd, brought close by equal tones.

A problem in interpreting the progression in Jones’s paintings at Capel is that dates can be uncertain. Working on paper pinned to a board he sometimes signed and dated pictures immediately, but some were left undated or else dated from imprecise memory years later. What is clear is that though he hit on the way forward early on, Jones continued to experiment.

In his first New Year at Capel it was so cold that working outside was challenging. Then it snowed and he was forced indoors, where he painted a Crucifixion mural in the temporary chapel and the tiny Sanctus Christus. High in the Black Mountains, the snow was long-lasting but he got out to paint again when it was melting. He said he ‘liked the look’ of it and had never seen such huge drifts, though it gave him ‘a kind of ill-at-ease feeling almost of foreboding.’ In a few paintings he tried out a naïve style, perhaps influenced by seeing paintings by André Derain or Ben Nicholson. In these he responded to objects that interested him with directness and simplicity rather than with naturalism. He walked along the lane west of the monastery to look up the valley towards the Mountain Gate. In one painting the disappearing snow reveals remains of tree-felling which might recall the aftermath of shelling. In another, snow has fallen from the trees but is lying in the fields and woods. Pale sunlight gives a yellow glow to the whiteness and casts blue shadows. He makes strong features of the trees and logs, the road swooping into the distance and the wall that separates the woods and fields from the unenclosed mountainsides above. He went down to the riverside for another view in the same area.

He tried another approach in a view of the monastery in February with snow still on the ground. The sharp angles and interpenetrating shapes give the painting an Art Deco quality; a hint of Vorticism. Nevertheless, it is an accurate depiction. It shows the monastery buildings on the right, the trees that separated them from the farm, the red stone of the orchard wall running down the hill and the ghostly, semi-derelict chapel, as yet with its roof.

Following his first ten-week stay in winter, Jones returned to Capel from August to October. Y Twmpa with Conifers must have been painted then, as deciduous trees are in leaf. This was the view he saw daily from the front of the monastery. He exaggerated the heights to be true to the feeling of the enfolding hills. Henceforth, the end of the Darren Lwyd ridge overlooking Capel (his ‘Twmpa’) appeared regularly, the cairn near the top picked out to punctuate the horizon. Another favourite motif was the farm opposite – Pen-y-maes, where he would walk for the milk.

The next year, 1926, was the annus mirabilis of Jones’s painting at Capel. He was there for half the year in total, in winter, spring and summer. He was out in nature drawing obsessively even though he was working simultaneously on major illustration commissions. He alternated between paintings that brought together all the characteristics of his new landscape style and others in which he tried varying approaches. In June he painted a view of a cascade on the Nant Bwch in such dense gouache that he used white paint to add the highlights. The warm colour and luxuriant vegetation seem fantastical, evoking The Lost World or the Garden of Eden. He makes a feature of the straight lines weathered in the stone. Yet from around the same time another painting of the stream employs translucent washes that leave white paper and fine work in pencil. The layering in the sandstone rhymes with the ripples in the stream rushing away amidst grass, ferns and trees.

In several paintings of the orchard at the monastery in both 1925 and 1926 he tried a mildly Fauvist idiom that employed opposite colours to create an energetic effect, perhaps influenced by Henri Matisse or André Derain. In one that looks diagonally down the orchard, northwards to the sheltering mountain, he celebrates the Capel community’s husbandry of the land: fruit on the apple trees, vegetable plots, straw bee-skeps and a wooden hive, new saplings planted alongside the bent old apple trees. In another picture done the previous autumn the fruit has gone from the trees and the pickers have left behind a ladder and a few pruned branches.

In the paintings of more settled style in 1926 the mountain captured Jones’s mind again and again. Y Twmpa, Nant Honddu has sparing colour, placed only where he wanted it to create form, and fluid pencil line is given status as an equal partner. He distorts scale and gives stability with a clever play of triangles – the summit, the wood below, the fields either side and inward-leaning trees. The view is a short walk up the lane from the monastery and the time must be high summer as he creates textures with woods, feathery foliage and lines of mowing. He drew the field shapes quite accurately judging by contemporary maps. Indeed, a review of Jones’s first exhibition the following year said truthfully that his paintings were ‘half maps and half pictures, with the distance between near and far abolished, but with considerable emphasis on the relief of individual parts – such as the folds of the hills’.

By July, when he painted Landscape at Capel, Jones knew his subjects intimately – the mountain with its skirt of woodland, the hillside farm, the monastery barns and the little stand of trees in the field below. Pale tones, delicate marks and prominent pencil under watercolour were all distinctive qualities of his paintings for the rest of his life, as was his ability to pick out emblematic details without shattering the composition: the scarred tree-trunk, the fence and the plough lines pointing towards Pen-y-maes.

John Rothenstein said about the paintings of 1925/6: ‘These drawings may be regarded as marking David Jones’s point of departure as a mature artist.’ One that he had in mind was Hill Pastures: Capel-y-ffin, which shows another aspect of Jones’s maturity: the abstract qualities he captures in his outlined landforms, the dead tree, the cross-hatching and patterning of wood and hayfield. Rothenstein recalled that he had seen it newly finished on his visit in 1926 and that Gill said it had been done from the monastery window. More plausibly, the view is from the unenclosed grazing above the monastery: the artist is not level with Pen-y-maes farm but looking down on it and the valley is hidden behind the hillside shelf where the ponies put down their heads to eat. The outcrops of ‘Twmpa’ are not facing the viewer but silhouetted on the right.

Jones achieved the fluidity and movement he sought in all of his new paintings but especially in those with mountains and woods. Y Twmpa is rich in curves and arcs and arabesques as well as staccato cross-hatching. He relishes the varied forms and textures of the trees, woods, ferns and grasses – he was already an admirer of the woodland drawings of Samuel Palmer and knew his heartland landscape in Shoreham. The view is from the lane just west of the monastery, looking down into the river meadow and up to Pen-y-maes. Jones keeps the rhythms flowing by cutting off the mountain peak, which would otherwise have drawn the eye.

It is clear that he was seeking significance in his paintings by this time; not just records of topography but signs of something beyond. The central stand of trees in Y Twmpa suggests the mystery of a refuge or a sacred grove. A few years after painting it he conjured in the last scenes of In Parenthesis a vision of the Queen of the Woods arriving to bestow tokens on the fallen: ‘The secret princes between the leaning trees have diadems given them’ of berries, myrtle, sweet-briar, saxifrage.

It would be hazardous to read ideas from his writings into the interpretation of paintings that came before them, but there is no doubt that his reading and thinking at Capel had begun a journey into meanings. The notion that nature manifested praise of God was explicit in the title of a painting just a little later, at Lourdes in France in spring 1928: Montes et Omnes Colles. The phrase comes from Psalm 148, in which all things in Creation are enjoined: ‘Praise ye the Lord … Mountains, and all hills; fruitful trees, and all cedars’. Nature was for Jones, therefore, a sign of God, a transubstantiation; and by manifesting nature, art achieved a similar condition. His Sanctus Christus of 1925 expressed the holiness he found in Capel-y-ffin: the cross is hewn from trees felled in the valley, the hills have been riven apart by the planting of the cross and the Honddu springs from its foot. Jones borrows details from the Capel landscape: the red soil, a footbridge, the monastery chapel, a Welsh pony and a heron in flight, though his primitive Christ may have been influenced by wayside shrines he saw in France during the war.

He did not need or expect his audience to share his associations. His friend Nicolette Gray wrote that allusions ‘come into his pictures because they are part of his mind, not because they are intended to be read by the beholder.’ Nevertheless, the meanings of objects became increasingly central. The clear mountain waters had holy connotations through St David’s links to the name ‘Honddu’ and through baptism and water as a sacrament.

He would explore in later works comparative mythology and connections between the present and the past as understood through Sir James Frazer’s Golden Bough, and sources as diverse as Maritain, Morte d’Arthur, the Gododdin, the Mabinogion, the Roman liturgy and Eliot’s The Wasteland. He read most of them before or during 1926. Already in his Capel paintings, the mountain ponies might be seen as relict from the ancient armies lost in battles: ‘Those straying riderless horses gone to grass in forest and on mountain’. The woods and trees may have brought to mind ideas about nature, refuge, the folklore of forests and the wood of the cross. He came to Capel only ten years after he had fought his way through Mametz Wood under constant fire. That might be echoed by the trees that edge a sloping field in Landscape at Capel-y-ffin.

The geographical reach of Jones’s painting at Capel was constrained. All his subject seem to lie in the valley of the Nant Bwch, many of them within a hundred paces of the monastery (see map inside back cover). He seldom drew on the open hillsides – perhaps preferring the trench-like protection of the valley, the more so as his agoraphobia worsened. However, he did sometimes walk further. During his first Christmas he got lost on a ridge-top in the mist with René Hague and walked with the Gills to the top of Nant Bwch. Some paintings appear to be located near Blaen-bwch, a farm beyond the Mountain Gate, where he walked with Petra, some 2 miles from the monastery. Here, the headwaters of the Nant Bwch flow between sculpted earthen banks. One wintry upstream view is all ‘hill-rhythms’ and movement: the profiles of the mountains and landforms interweave, trees lean and a slope has slipped into the river to reveal the red Breconshire soil. Another (possibly unfinished), in which smooth tumps contrast with rocks and dead trees, seems to be the reverse view, south-eastwards towards Capel.

Jones took no interest whatever in a wealth of other prospective subjects. He never drew the distant views from the mountain tops. He did not walk down to Llanthony Priory in homage to Turner. He was never captivated by the little church that charmed Kilvert with its owl-like turret, nor by the high-banked lanes or Baptist chapel that so fascinated Ravilious when he arrived in Jones’s footsteps. Jones limited even the monastery to appearances through the trees or above the fields.

His subject was instead the natural essence of Capel-y-ffin, freighted for him with spiritual, mythical and personal meaning. It was the Capel of his mind: a magical, enclosed and all-round space of water, woods and mountains. In two years, in his responses to this cherished place, he had redefined himself and become an artist unlike any other.

This is an extract from the catalogue essay by Peter Wakelin accompanying the exhibition Hill-rhythms: David Jones + Capel-y-ffin, 1 July to 29 October 2023, y Gaer: Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library, Glamorgan Street, Brecon.