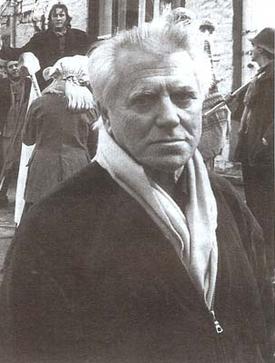

Author and editor Dylan Moore discusses John Hughes’ establishment of the city of Donetsk in the context of Gwyn Alf Williams’ documentary Hughesovka and The New Russia.

‘Three times has this city been the focus of a struggle to create the new Russia.’ The words of one Gwyn Alf Williams, introducing the BAFTA Cymru-winning three-part documentary series Hughesovka and The New Russia, directed by Colin Thomas, first aired on BBC2 in 1991. Like Byzantium-Constantinople-Istanbul, the city of Donetsk in eastern Ukraine has had three names and a turbulent history, but its history is as short as Istanbul’s is long. Its founder, Merthyr-born engineer and entrepreneur John Hughes, arrived in 1870. Now, less than 150 years later, the city – originally called Hughesovka in the Welshman’s honour – for a fourth time finds itself at the frontier of that battle for The New Russia.

As Hughes’ fellow Merthyr Boy Gwyn Alf Williams points out in the mini-series, Donetsk has been – throughout its entire history – ‘a microcosm of Russia’. It is an almost outrageously bold claim that such a place could exist, given the nature of the world’s largest nation and the turbulence of its history, but words spoken as narration on a relatively obscure Wales-made documentary seem remarkably prescient to the current geopolitical faultline forming in eastern Ukraine.

Despite that UNESCO’s ‘most beautiful industrial city in the world’ was, when Williams visited with BBC cameras in 1991, looking forward to a time of greater peace and prosperity, the history he recounts is more indicative of the region’s propensity to spill into violence. From its earliest days, there were the atmosphere, social conditions and unrest common to hard-bitten immigrant-built industrial towns like the one Hughes had left behind in South Wales. Hughesovka of the 1890s must have been a little like the Merthyr of the 1830s, complete with ‘flames, smoke, thunder, drink and disease’; it even had a sizeable Welsh workforce that Hughes had imported from Dowlais, Maesteg, Swansea and Blaenavon.

But, along with the 1892 Cholera Riots, there also were frequent pogroms that have alarming contemporary resonances in the neo-Nazi developments gripping the region, with reports of today’s Jews in Donetsk being forced to ‘report their nationality’ or face expulsion. Reminding us that the Russian Civil War – which had its Ukrainian episode in 1918 – killed fourteen million people, Williams says ‘there were Red armies, White armies, Ukrainian armies, German puppets and private armies’. A century on, the confusion, fragmentation and foreign interference are depressingly familiar.

Williams goes on to trace, in his inimitable style, some of the parallels between his native South Wales and the Donbass region, all the while acknowledging that, for all the extreme poverty and radical politics in 1930s Wales, in Stalino – as the city was renamed in 1924 – the suffering was on a completely different level. Thousands died of starvation before Lenin’s New Economic Policy put mining, steelworking and education at the forefront of the city’s reconstruction. Briefly, the new Yuzovka – it could hardly retain the name of a Western capitalist – was named after Trotsky, ‘organiser of the Red Army and hero of the civil war’ but then as he was airbrushed from history, the city settled on a ‘nice safe neutral name’ – steel town. As Williams wryly notes, ‘The word stalin simply means steel – but it was a choice that was to prove singularly prudent!’

A communist himself – of the generation politicised by the Spanish Civil War – Williams pulls no punches when it comes to the ‘shattering’ impact of Stalinism. Like a heads-of-the-valleys latter-day Orwell, he recounts how the Donbass was overrun with ‘idealists, careerists and half-literate peasants’ who enacted a ‘communism without communists’ as the Soviet Union ‘urbanised overnight’. He talks of the ‘murderous lunacy’ of a period in which there were one million ‘official’ executions and countless more besides, with at least eighteen million passing through the gulags. In Ukraine ‘there was a relentless assault on national identity, intellectuals and the church’; Williams talks to survivors about the widespread starvation, conditions that led to instances of cannibalism and the fact that even among the privileged managerial class ‘every day someone went missing’.

If the current crisis in Donetsk is, at present, a far cry from such horrors, there are warnings from history in the confusion surrounding the identity of ‘protestors’. Are they Russian infiltrators? Local militias? Ordinary people concerned for the future of the country?

There are troubling echoes too of the next stage of Stalino’s violent story. In his documentary, Gwyn Alf Williams paints a particularly vivid picture of the treachery and violence that ripped through the city in the wake of the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As the unlikely communist-fascist agreement broke down and the Germans rolled into Stalino in October 1941, the Russians operated a scorched earth policy. The Nazis threw hundreds to their deaths down mineshafts but some Ukrainians welcomed the Germans as liberators, such was the brutality of the Stalinist regime. Before long, however, they became sickened by Nazi treatment of ‘subhuman Slavs’ and ‘subhuman Jews’ – a quarter of a million were killed in prison camps during the two-year occupation of Stalino.

75 years after John Hughes had arrived on the steppes from Merthyr Tydfil, the city he founded as Hughesovka had endured untold suffering. By the time Nikita Khrushchev – ‘local boy made good’ – came to power, preaching what Williams calls the ‘boundless optimism’ of the ‘communism of the future’, the Soviet Union had become an ‘organised hypocrisy with corruption running through it like black slick’.

However, returning in 1991, Williams cannot help but to romanticise a ‘beautiful city of broad boulevards, spacious squares, 500 libraries… roses everywhere’, where ‘in the culture, miners are heroes’. There is a sense in which the old communist is attracted to a city, long since renamed for a third time – ‘Donetsk, jewel of the Donbass region’ – because in March that year it found itself ‘the Mardy, the Tonypandy’ of a Miners Strike that was to rock the very foundations of the Soviet Union and pave the way for the independent state of Ukraine that has retained a territorial integrity until this current crisis.

But it is instructive to revisit Williams’ documentary now, because even then – in 1991 – the historian noted, with an eye that sometimes journalism lacks, that there were ‘Ukrainian flags, but little Ukrainian nationalism – their politics is confused’. He is intrigued in his conclusion by the way ‘this genial but confused town, celebrate[s] the Welshman who created it: a classical nineteenth century capitalist’ giving birth to a ‘community even more wretched than his predecessors had created in South Wales’. Williams’ unique perspective allows him to understand Donetsk as ‘a tissue of contradictions’: ‘roses bloom because disease bearing spores cannot live in the polluted air’.

The documentary ends on a note of hope, as if Hughesovka is emerging finally from the long, dark mineshaft of its history. There are carnivals instead of marches, and a church built by Hughes is full again of young people with their children. We are left with footage of children going to school on the first day of term. ‘From these kids may come the people who may create a decent life and a decent society here… God in heaven, they’ve earned it!’ Williams exclaims. But his hope is tempered with a chilling undertow of caution: ‘When I think of those black monsters out of Russia’s dark past’, says Williams, ‘my stomach turns over.’

Those kids, Williams’ symbols of hope, will now be in their twenties and thirties. Some of them are now, no doubt, occupying public buildings and declaring a separatist state, or an allegiance to Mother Russia; some of them ‘protesting’ for one faction or another; some of them cowering at home, fearing that their city once again finds itself on a key square of the global checkerboard. All of them are pawns in a game being orchestrated from the Kremlin and the Pentagon. In this steeltown on the steppes, founded by a Welshman, history doesn’t roll on, it rolls over.

Dreaming a City: From Wales to Ukraine by Colin Thomas was published by Y Lolfa in 2009. It is accompanied with a DVD featuring the complete series of Hughesovka and the New Russia.