Latest in our new series where we ask writers and artists to defend the seemingly indefensible, to put forward the case for some much-maligned creation, S. Mark Gubb tells the story of how Abel Ferrara’s infamous 1979 Video Nasty, The Driller Killer, changed his life.

My Father has always been something of an early-adopter where it comes to technology. In his bedroom wardrobe, you’ll still find a Sinclair ZX81 stored alongside a BBC Micro Model B computer, so it was no great surprise when early on in the home video revolution we found ourselves returning from a Saturday morning shop with a Ferguson Video star Toploader. The technology meant little to me at the time, but it opened up a whole new world of trips to the local video store. This was the early 80s, I was only seven or eight years old and it was long before Blockbuster had taken hold of the global video market, so we had a choice of two stores in my town – Southern Video or, the inexplicably named, Virgin Video. The latter had nothing to do with Richard Branson and its name just compounded any doubts my Mother may have had as to the potential bad influence of these new-fangled machines, so our allegiance was to Southern.

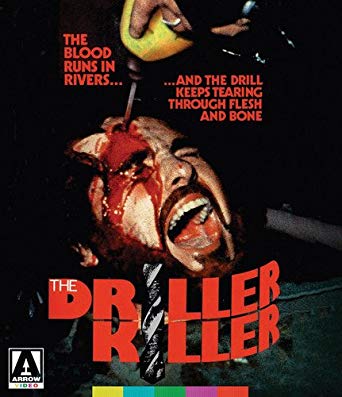

I clearly remember my first encounter with Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer. During one of our regular trips to the store, the video-box cover image positively leapt off the shelf at me – a bearded man, screaming in pain, as a drill burrows into his forehead. I don’t recall feeling scared or horrified by the image, just grimly fascinated. It alluded to something that was way beyond my reach at the time – a blood-soaked forbidden fruit, only to be accessed by adults, the keepers of the treasured membership card. It would be decades before I got to watch the film, or even to know what it was about, but I would look to catch a glimpse of the cover whenever we went to the store until, one day, it was gone. I remember wondering why until my much-older cousin who had managed to get in to see The Evil Dead at our local cinema even though he wasn’t 18, explained to me that a group of films had been deemed so violent and scary that they had been banned. These included the aforementioned Evil Dead and they had been banned under what was to become the 1984 ‘Video Recordings Act’. The 80s was an interesting time for moral panic. In a period where we had the very real and ever-present threat of nuclear holocaust, people expended a lot of time and energy worrying about things like video nasties and the purported Satanic content of rock and heavy metal recordings (it’s no coincidence that I’ve grown up obsessed with all of these things).

I clearly remember my first encounter with Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer. During one of our regular trips to the store, the video-box cover image positively leapt off the shelf at me – a bearded man, screaming in pain, as a drill burrows into his forehead. I don’t recall feeling scared or horrified by the image, just grimly fascinated. It alluded to something that was way beyond my reach at the time – a blood-soaked forbidden fruit, only to be accessed by adults, the keepers of the treasured membership card. It would be decades before I got to watch the film, or even to know what it was about, but I would look to catch a glimpse of the cover whenever we went to the store until, one day, it was gone. I remember wondering why until my much-older cousin who had managed to get in to see The Evil Dead at our local cinema even though he wasn’t 18, explained to me that a group of films had been deemed so violent and scary that they had been banned. These included the aforementioned Evil Dead and they had been banned under what was to become the 1984 ‘Video Recordings Act’. The 80s was an interesting time for moral panic. In a period where we had the very real and ever-present threat of nuclear holocaust, people expended a lot of time and energy worrying about things like video nasties and the purported Satanic content of rock and heavy metal recordings (it’s no coincidence that I’ve grown up obsessed with all of these things).

For those reading this who have never seen it, and I assume there will be many, The Driller Killer is about an artist called Reno Miller, a painter, who is struggling to finish a new work he believes will be the end to all of his financial woes. He has a complex relationship with the homeless, who are many on the streets around his Union Square apartment and studio in Manhattan, and an early scene suggests his father may well be one of their numbers. Whilst struggling to finish his painting a local punk rock band move into an adjacent apartment, noisily practising night and day, and the film charts the break up of his personal and professional relationships and his gradual descent into murderous insanity brought about, in no small part, by the scorn and derision heaped upon him by the art world.

There have been many analyses of this film over the years; you only have to do a quick Google search to find them, so I’ll spare you my own, mainly as it won’t differ much from what others have to say. But what I can offer is why I remain so nostalgically attached to this film and why I think it’s worth 96 minutes of your time, even once.

Let’s be honest – The Driller Killer is not a ‘good’ film. It’s badly acted, clumsily directed and struggles to keep your interest at times. In almost every way it looks exactly like what it is – a film made by an art school graduate learning their craft, making mistakes, figuring out how to tell a story – but that’s not the point. What comes through is a developed and sincere desire to discuss something more than the story at hand. The film may be about a struggling artist and his slide into insanity, but what it portrays is something relevant to its time – a financially depressed Manhattan, poverty, homelessness, the dispossessed, the insecurity of a creative life – all of the things that would have been Ferrara’s reality. It was released in 1979, having been filmed over the two previous years and, for me, it’s as much a portrait of late-70s New York as Warhol’s ‘Chelsea Girls’, ‘Empire’ or his ‘Screen Tests’ were of the 1960s. Almost certainly not by coincidence, much of the action takes place around Union Square, home to Warhol’s ‘Factory’ studio between 1967 and 1984. Other scenes are filmed in the legendary Max’s Kansas City music venue and the infamous NYC subway, none of which would have been remarkable at the time, but all of which have become cultural icons in their own right. The landscape this tale is projected on to is the living and breathing New York that I would romanticise and obsess over as a teenager, whilst feeling a million miles away from it in time and space.

Let’s be honest – The Driller Killer is not a ‘good’ film. It’s badly acted, clumsily directed and struggles to keep your interest at times. In almost every way it looks exactly like what it is – a film made by an art school graduate learning their craft, making mistakes, figuring out how to tell a story – but that’s not the point. What comes through is a developed and sincere desire to discuss something more than the story at hand. The film may be about a struggling artist and his slide into insanity, but what it portrays is something relevant to its time – a financially depressed Manhattan, poverty, homelessness, the dispossessed, the insecurity of a creative life – all of the things that would have been Ferrara’s reality. It was released in 1979, having been filmed over the two previous years and, for me, it’s as much a portrait of late-70s New York as Warhol’s ‘Chelsea Girls’, ‘Empire’ or his ‘Screen Tests’ were of the 1960s. Almost certainly not by coincidence, much of the action takes place around Union Square, home to Warhol’s ‘Factory’ studio between 1967 and 1984. Other scenes are filmed in the legendary Max’s Kansas City music venue and the infamous NYC subway, none of which would have been remarkable at the time, but all of which have become cultural icons in their own right. The landscape this tale is projected on to is the living and breathing New York that I would romanticise and obsess over as a teenager, whilst feeling a million miles away from it in time and space.

And then it plays this peculiar role in our own, very British, cultural history. The creation of a new law in response to a perceived moral threat, so significant that an entire episode of ‘The Young Ones’ was based around it, featuring The Damned playing their song ‘Nasty’ (with Cardiff’s-own Bryn Merrick on bass – R.I.P.)…

Catch, catch a horror taxi

I fell in love with my video nasty

Catch, catch a horror train

A freeze frame goin’ to drive you insane

The Driller Killer won’t change your life, for better or worse, despite what our moral guardians would have us believe. But it’s an important marker in our cultural and sociological history, on both sides of the Atlantic. And as a visual artist myself, there’s more than a little bit of me that can relate to Reno’s creative struggle and craving for validation and success, whatever that really means.

Now, where did I leave my drill…

You might also like…

Hayley Long offers an impassioned defence of cassette tapes in the latest in our series of essays on some of the modern culture’s most maligned items.

For other articles included in this collection, go here.