Beth Pyner was at the Reardon Smith Lecture Theatre in Cardiff for The Power of Instagram: A Symposium to take in a series of discussions and lectures on the style and evolution of social media’s most influential platform that looked beyond the celebrity porthole.

Since its launch a decade ago, Instagram has seeped into our lives, becoming the go-to social media platform for sharing photographic updates of our every day: from food to selfies, and from holidays to fashionably small dogs. Amid the overwhelming visual noise of the constant posts produced by Instagram’s one billion monthly users, the platform’s focus on the visual has prompted significant shifts in our use of photography, as well as scholarly and artistic understandings of photography, art, and communication. These shifts can be easily overlooked and disregarded, perhaps due to a preconception that Instagram is driven by a potent combination of consumerism and celebrity. ‘Instagram: A Symposium’ sidestepped these assumptions, instead of engaging with the platform’s multifaceted existence: considering Instagram’s place in contemporary photographic practice, as well as its uses for artists and creatives.

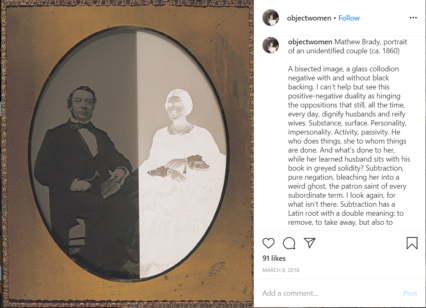

As we shuffled out of the cold and into the red velvet plushness of the beautiful Reardon Smith Lecture Theatre, I was uncertain of what to expect. But the symposium soon unfolded with a fascinating address from Dr Alix Beeston, making enticing links between the early-twentieth-century work of German documentary photographer August Sander and Instagram. Sander documented ordinary people, arranging their images in one of seven categories, each of which, for Sander, represented unique but equal roles within society. Sander’s categorical arrangement, his mosaic of humanity, argued Beeston, both reflected and entrenched social identities, his serialized images foreseeing not only the gridded structure of Instagram but also the replicable nature of contemporary selfie culture. And if that introduction wasn’t enough to grab the attention of any audience member harbouring doubt about the depth of Instagram’s influence, there was certainly a lot more to come: from Professor Alexandra Georgakopoulou’s analysis of Instagram’s evolution from selfie to ‘story’ feature, via Dr Alexandra Kingston-Reese’s analysis of ‘Instapoetry’; from Beeston’s digital project @objectwomen, subverting the male gaze of photography’s representations of women, to Celia Jackson and Huw Alden Davies’ revisited childhoods; and from Michal Iwanowksi’s Go Home Polish, an Instagram-hosted art project challenging the xenophobia he’d experienced in post-Brexit Britain, to Federica Chiocchetti’s reflections on Instagram as a promotional tool in an increasingly digitised world.

For me, the common thread that united these diverse talks was the concept of power. Dr Cadence Kinsey explored the issue of authenticity on Instagram via a (now infamous) work of art, originally hosted on the platform, in which artist Amalia Ulman (@amaliaulman) undertook a five-month-long, three-part performance piece, hoaxing her own life. Ulman gained nearly 90,000 followers during the project and faced strong criticism from them when the jig was up, and the truth revealed in her dramatic finale. The power dynamic here is clearly complex. Kinsey highlighted the power of the influencer to choose what they present to the world in an endless act of personal curation. But the power of the backlash, a cacophony of individual users rallying against an individual, is also immense. In reality, noted Kinsey, on Instagram we’re all the product rather than the consumer, feeding Instagram’s profits via social media’s well-established model of paid-for advertisements, tailored and tweaked by our every digital move. Given that the project was subsequently exhibited at several galleries, including the Tate Modern, what does this say about Instagram’s power to influence the art world, or the art world’s power to harness Instagram? And what is art, anyway, if we are all performing to Instagram’s lens, all the time?

Georgakopoulou, meanwhile, explored modes of female self-empowerment established or enhanced by Instagram’s reach. The average selfie-taker is a young woman, aged 24, who takes six to ten snaps before posting just one, established Georgakopoulou. Is this inverting the male gaze or an act of self-objectification and sexualisation? Instagram’s later introduction of the ‘story’ feature appeared to turn this on its head, replacing the ‘sexy’ selfie with the ‘goofy’ or ‘ugly’ selfie-and reflecting a more holistic self-representation. I can’t help but think, however, that the consequent backlash against the ubiquitous sexy selfie that evokes accusations of female narcissism, is the digital equivalent of the ageless quest to control and police female sexuality. So is there a winner? No, concluded Georgakopoulou, predicting ominously that selfie culture would continue to evolve, inevitably supporting the facial recognition cultures of the not too distant future.

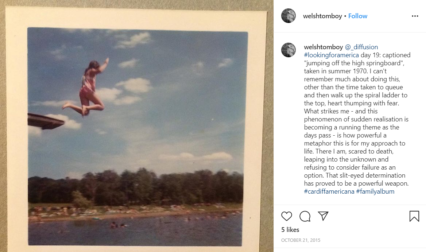

Other sessions spoke to the power of assemblage that comes with the territory of a digital photographic platform. Jackson returned to the traditional photographic albums of her childhood in 1960s America, pristinely assembled and preserved by her parents. Reassembling this content for an Instagram project has clearly been a cathartic exercise for Jackson, allowing for the reconfiguration of the self, the renegotiation of familial dynamics, and the reification of details from personal memory, ultimately subverting the powerlessness of childhood. Davies’ project Xennial, extended upon these themes. Wanting to recreate his youth in a small ex-mining village on the cusp between Generation X and Millennials, Davies has produced a multi-source archive across Instagram and other platforms, both digital and physical. Instagram, Davies suggested, enables a form of artistic communication more intuitive for Millennial and Gen Z audiences. Digital platforms such as Instagram, therefore, embody the power to engage with wider audiences, but also to archive memories and ways of living that might otherwise be lost. It’s important to remember, he stressed, that Instagram itself is not a permanent archive, but one that should be archived itself. This suggests to me that Instagram will inevitably be swallowed by its own present power, eventually falling victim to the replicability inherent to its success.

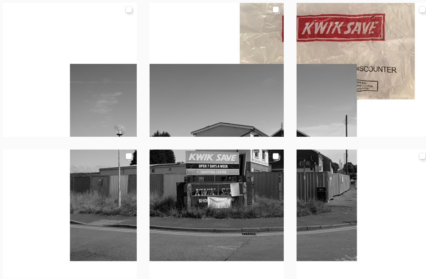

In the final panel of the afternoon, Iwanowski demonstrated the power of Instagram to turn unpleasant, in his case xenophobic, experiences into a source of community and comradery. Having seen ‘Go home Polish’ scrawled in graffiti, Iwanowski won funding to conduct a digital art project documenting his 1,900km journey to his birthplace in Poland from his home in Wales. Hoping to challenge the concept of what home is, and who gets to define a person’s belonging, Iwanowski found that Instagram was a perfect home for his project: #gohomepolish’s digital environment brought tens of thousands of people together, supporting Iwanowski’s journey, and standing up against racism and xenophobia.

The success of this project, however, also taps into the issue of Instagram, power, and the art industry at large. Several of Iwanowski’s photographs have since been shown in galleries: Iwanowski built a short, elongated panel for displaying the images, replicating their original format as seen on a smartphone alongside their Instagram captions. This development arguably epitomises the impact of Instagram on photography and art: from social media to social movement, to gallery. Some of Iwanowski’s images have been acquired by National Museum Wales, so watch this (digital) space to see for yourself the impact of Instagram on curatorial practice.

By the end of the afternoon, my mind was full to bursting. Our allotted time over, stretching the seams of the compact schedule, there were clearly many more avenues to explore, discussions to begin. ‘Instagram: A Symposium’ was engaging and knowledgeable, treating the issues it addressed with depth and urgency. But, most excitingly, it only scratched the surface.

As we shuffled back out of the lecture theatre, back into the cold, I couldn’t help but reflect on Beeston’s words about the ‘certainty’ of Instagram. The certainty of shooting, selecting, assembling, and its sharp contrasts with the ‘randomness’ of traditional, and in some cases historical, photographic practices. From the experimental chemistry of the original dark rooms to the anticipation (or dread) of what would return from Jessops in exchange for the negatives of my childhood. Surely there is power in this knowing, power in this certainty?

This article is presented in partnership with Image Works: Research and Practice in Visual Culture, a public initiative of the School of English, Communication and Philosophy at Cardiff University.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.