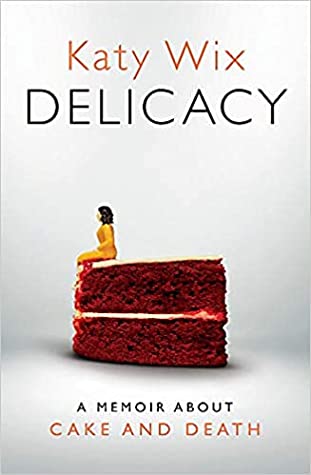

In just under two years, writer and actor Katy Wix lost her best friend and both her parents in a devastatingly short amount of time. This heartbreaking experience became formative in the writing of her acclaimed memoir, Delicacy. Recounting Wix’s experience growing up in Cardiff, the incubation of body image issues, as well as the aftermath of her profound bereavement, Delicacy provides a deep-dive into grief and emotional vulnerability. Caragh Medlicott caught up with Katy over Zoom to discuss writing, grief and diet culture.

Caragh Medlicott: I wanted to start by talking about the emotional labour of writing such an intimate memoir. At the very opening of Delicacy you write, “the important thing was to excavate the emotional truth […] and, by writing, maybe lay it to rest”. I was looking up the etymology of the word ‘memoir’ the other day and Google informs me that it’s from an Old French word meaning “something written to be kept in mind”. I wondered if that resonated with you — that writing this memoir wasn’t only about processing what happened but being able to turn the page on the experience knowing that, if you wanted to, you could go back to it?

Katy Wix: Yes, you know, there’s this amazing poetry collection by Rebecca Goss [Her Birth], where she writes about the death of her daughter and she said that, in writing it, she felt at times like she was prolonging her grief. And that quite haunted me because there were times where it almost felt slightly masochistic, the degree to which I was so obsessed with the detail; it was draining the amount of energy I had to give to go back over the memories. So it was almost like keeping it alive, sometimes in a bad way. But then, curiously, now when I see the book — the physical object — I sort of think of it as all being stored within it and I think, that’s done.

A really common question I get is whether it was difficult to write about this personal stuff. I always want to say, yeah, it was — but what’s more difficult is just making a good piece of writing. More the technical aspects of just, you know, writing and editing and making something work — making it flow. Good writing really quickly became the thing I was most obsessing over.

Caragh Medlicott: I really felt that your voice and style were so clear throughout the book. I always think there is something quite lonely about prose in particular. I wondered how you approached writing it, and how you found the transition from the script writing you’d done previously?

Caragh Medlicott: I really felt that your voice and style were so clear throughout the book. I always think there is something quite lonely about prose in particular. I wondered how you approached writing it, and how you found the transition from the script writing you’d done previously?

Katy Wix: Yeah, it was so different. But actually, the loneliness I really revelled in because I’m so used to writing in collaboration with other people and I think — because I’ve mostly written for TV and radio — you go through so many other people’s notes, and then there’s often a kind of gatekeeper at the top, so it was liberating to have none of that. As soon as I realised my editor was really supportive and happy to go with my more experimental ideas, I relished that creative freedom. If you compare it to TV writing, it was like I was the director, the producer, the writer and the costume department all in one.

Of course it was still lonely at times. It was a very stressful three years and there were points where I felt like I was having a breakdown simply because it was all on my shoulders. It felt like an immense pressure and there was a lot of self-doubt. But I also have a group of readers now, people I trust, and one person in particular who has read many more books than I have and is far smarter than me. I feel like that would be my biggest piece of advice to new writers, to find great readers you can trust.

Caragh Medlicott: I watched the YouTube interviews you did to go along with the book and heard you say that reading other people’s memoirs sometimes jogged your own memory, and that reading other people’s stories in general was more enriching than self-help books. It made me think of a quote from Kazuo Ishiguro: “In the end, stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. […] Does it feel this way to you?” — I wondered, how much did you think about the reader when you were writing? Was there anything you hoped people would take from it?

Katy Wix: What a great quote, I love that. I think at the start it was definitely more selfish — I was writing for myself because I enjoy creating and it’s very therapeutic to me. I also think it keeps me sane. It’s almost like a compulsion, the drive I have to create a good piece of work. It was also partly because I felt like something had to come out of the total shit show I’d been through. There was also even a slight sense of anger, at times, the injustice of it — I’d literally become an orphan. I didn’t feel like I had a voice. So my baser self was almost wanting revenge, but then there was also my higher self which thought you know, someone might find this useful.

I didn’t feel pressure to give any kind of guide on how to cope with grief. I didn’t even feel particularly pressured to write a positive ending, it just happened. I think because I’ve come from writing comedy I felt so self conscious of the shifts in tone. To have been in comedy for so long, where everything is steeped in irony, to suddenly be so sincere was hard. That’s partly why reading would help me so much because I could see things that were worth saying without joking. The reader ultimately came to the forefront of my mind when I was in the editing process. I’d written everything down and the first version was almost like a journal so then I had to turn it into something more. I was really just aiming to be fair and honest.

Caragh Medlicott: Talking about shifts in tone, something I really liked about Delicacy was the variety of writing styles. Like the funny email exchange with your personal trainer where you underlined lies and added in extra comments in italics.

Katy Wix: You know, we recently recorded the audiobook and when we got to that bit it was really weird. I hadn’t even thought about that chapter and how I was going to convey it — I was like: Am I going to change my voice? Am I going to whisper? It sounds a bit like a pantomime. It works on the paper but reading it aloud it got a bit complicated.

Caragh Medlicott: It’s not the only style you use, you have the numbered list of thoughts on cancer, and the letter addressed to your friend. What I really liked about that was that it felt more true to life because memory and emotions aren’t uniform; we don’t experience them like a flashback in a movie. What motivated the decision to incorporate those different styles?

Katy Wix: Yeah, I totally agree. Like, particularly with the numbered chapter, the one to do with cancer. I feel kind of guilty, because it’s also such a ripoff of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets which I’d read a couple of months before and felt really inspired by. But also I just thought it was a much closer way of documenting how I was experiencing things. I was thinking a lot about trauma and memory and how things would suddenly come back to me at 3am. Grief is a lonely place, and it’s such a mass of thinking all at once. I think when it comes to something as profound as losing a parent you enter into a realm of such layered thinking, it’s so complex and amorphous. I was trying to work out how I felt and numbering it made me feel like I was organising it — but not necessarily in a narrative way. It made it exciting and freeing somehow. I would think to myself — what does this feel like? But then I would realise it wouldn’t make sense on the page, so this was a way of translating it.

Also, if I’m really honest, I have a short attention span and I really find structure quite intimidating. Even now. I always feel as though everyone else has read some book that I haven’t read on structure. I feel like there are rules I don’t know about, so I’m still learning. The thing with structure is that it can be so technical, especially in script writing. I’ve had notes back before now where people have said “this scene should happen on page 20” — so formulaic, as if it’s geometry. But for me, I just have to be more intuitive with it. Of course, reading helped too, I’d recently encountered prose poetry properly for the first time and it was like a door just opened in my head and I thought, these are like scenes. These can just be really specific contained moments with little borders around them.

Caragh Medlicott: I always think that prose poetry is closer to the reality of how we experience emotions anyway. We sort of impose a narrative after the fact.

Katy Wix: Yeah, exactly. And I think that those numbered fragments made sense because I felt like I was outside of normal time. It’s such a cliche, especially when someone dies, to say that time stops, and I don’t think it did stop, exactly, but it changed. I felt outside of other people’s time. Their lives were just carrying on and that becomes an outrageous idea when you’re grieving.

Caragh Medlicott: Yeah, it’s weird because we spend our whole lives saying to the people we love “I don’t know what I’d do without you” — but there’s obviously, at some point, a time when we have to figure it out.

Katy Wix: Yeah it’s like the cognitive dissonance we need to go about our lives. Otherwise we’d all just start screaming. I think before I experienced loss, I didn’t really think about it. And I think that’s kind of correct — I feel like when you’re young you shouldn’t think about it. There’s a friend of my mum’s who I suppose must be in her late 50s who still hasn’t lost anyone. Like she still has her grandparents and she kind of just looks frightened. I think it’s an emotional privilege, in many ways, to go through your 20s and not lose anyone. I have friends who lost a parent when they were really young and I think they just kind of had to park it and deal with it later.

Caragh Medlicott: One of the things that struck me while reading your description of grief was that idea of “hoarding time”. Do you think that our society is impatient with grief, where after a certain period people don’t want to be reminded of it because it makes them uncomfortable?

Katy Wix: Well, there is this amazing book called The Shame of Death, Grief, and Trauma — it’s sort of like a psychological manual, in a way. I remember seeing the title and wondering what it meant by the shame of grief. There’s this chapter in it which explores the shame of having to bring death up. I think it’s so outside of the social norm. The profundity of it and the strangeness of it, it almost makes it a bit embarrassing. Like there would be times I’d be making small talk with someone and then I’d have to say, “anyway, I’ve got to go, my mother is dying”. Or when I’d just start crying in public. There was an awkwardness there — a breaking of the rules somehow.

Also, I think it’s sort of internalised to feel like you’re somehow attention-seeking or just being a burden or something. Financially I was so lucky that I was self-employed and in an industry that is mostly compassionate — that I had savings so I could take time out to grieve. I’ve got so many mates, especially back home in Cardiff, and they just couldn’t do that. For a lot of people it’s like a week off, and then you’ve just got to get on with it.

Caragh Medlicott: It’s almost unfathomable that people are expected to function after such a short period of time.

Katy Wix: Yeah, it is. I know it depends on the context of the death and everything else. Like with my friend, it was very sad and brutal. I would actually say I was dealing with shock for the first six months. Grieving is one thing and shock is a different thing altogether, it’s such a strange, physically demanding experience. It’s almost violent and after it you feel like you can’t remember anything. It still hits me all the time, the grief. Sometimes I’ll go for months and months without getting upset. I pack it all away to keep functioning. But then it catches up with me out of nowhere. It feels very cyclical at the moment, like every six months I’ll have a couple of big grief days.

Caragh Medlicott: Another thing I’d really like to talk to you about is body image. When I was reading Delicacy I found a lot of my own memories coming back — one was a really strong recollection of being confused as a kid when women would say they felt “guilty” for eating something. I just remember thinking, you feel bad about fibbing or fighting with your siblings, but not about something nice like ice cream. It’s weird because now I’m trying to relearn something I knew inherently as a child. Do you think for women raised in our diet culture it’s possible to develop or even maintain a normal, neutral relationship with food?

Katy Wix: It’s so interesting, that idea of guilt. In school you’re taught about this very clear world of right and wrong that isn’t really there. But it’s so confusing because no one has to say to girls directly that food is bad but these messages are transmitted — consciously or unconsciously — through our mothers and the people around us. When I interviewed Susie Orbach [author of Fat is a Feminist Issue] she was saying that in our culture it is almost impossible to be fully healed, but if you’re kind of 80% recovered, that’s a really good place to be.

Ultimately it’s going to be a lifelong thing. For me, I’ve realised it’s so integrated into my sense of self. When I was in my 20s and I first went to therapy, we would talk about various things but it wouldn’t even occur to me to talk about what I was going through with food. I didn’t expect there to be a solution there. Women around me said things like, you know, being a woman is just starving and occasionally having some pudding at Christmas. This was presented to me as just to be expected.

Caragh Medlicott: I was thinking the other day about those little souvenir magnets you can buy, the kind mums love, where they say stuff like “I’m watching my weight — but it’s not going anywhere!”. It’s a joke, but also it points to the longevity of it — of how it’s taken as given that women are always dieting.

Katy Wix: Susie Orbach really made me laugh when I was speaking to her the other day because she said this thing about how she suspects that men think that women enjoy it. Like this, continual dieting, as if it’s just a thing that women do. Like, we haven’t stopped to ask ourselves why we’re doing it or if it’s enjoyable. As if it’s on par with shopping or something. Leaving that diet culture is almost like leaving a cult — except the cult is mainstream.

Caragh Medlicott: I try to practice intuitive eating but what I find really hard is when I’m faced with other people who are obsessing about food and calories. It’s so hard not to be sucked back into it, you end up almost feeling like you are failing, in some way, by eating what you want.

Katy Wix: It’s funny, isn’t it? Something I wanted to explore when I was writing was this atmosphere I felt growing up. One I didn’t really understand at the time but, retrospectively, had to do with being objectified. Like wearing a pretty dress and being told to do a twirl as a child. That feeling of being an object which ultimately led to self-objectification. In a weird way, writing has been one way out of that. Like I know when I can manage to see myself as a whole person I have a much nicer day, right? So when I seriously sit down to write it’s liberating, I have this feeling that I’m just a brain — that it’s just me and my words — no one is looking at me. I was really exalted in that feeling; I found it very healing.

Caragh Medlicott: I also wanted to talk to you about the broader idea of sensitivity. It does often seem that our culture sees sensitivity and vulnerability as a bad thing. Do you see your own vulnerability differently now, and if so, do you think that writing about it has been part of that change?

Katy Wix: Yeah, certainly. I think getting a bit older helps. And I guess realising that, actually, what often happens when you tell someone the truth of how you’re feeling, or something you feel is shameful, is that they react in a totally fine way. They say, “that’s fine — I still like you”. But it’s taken a long time. I still find subtle ways to avoid being vulnerable even now, and I catch myself doing it, and it’s interesting noticing when it happens. I still think like, if you watch someone being very open and raw in a stand-up show, I think that’s so brave, because with the book it’s still a one-sided conversation. I was able to control the level of vulnerability.

As for sensitivity, it is something I’ve embraced more. I think I was raised in an atmosphere where you didn’t show people the truth of how you’re feeling. I always felt more that it was my job to make sure other people were feeling okay. Women are raised to put others’ needs before their own. It means it doesn’t feel natural to say, “oh actually I don’t feel good about this”. It takes confidence — so there is strength in that. My mother used to say that being sensitive was just the price you paid for being a creative person and I do think there’s some truth in that — but it’s almost like it can’t be valued unless you can commodify it. I have read some really interesting stuff about the idea of sensitivity being a trait that’s inherited. Some people are wired differently and they might actually just experience the world in a different, more intense way.

Caragh Medlicott: Do you have any more writing projects coming up?

Katy Wix: Yeah, I do, but the problem at the moment is finding one idea and sticking to it. I’m at the very beginning of seeing if I can adapt Delicacy for TV. If I can, it will be centred around a family growing up in Wales, probably more of a drama than comedy, but a bit of both. It’s been more challenging than I thought, actually, because I’ve deliberately written something which doesn’t follow a neat, linear story. So I think using a lot of flashbacks will be the only way to do that.

I also have an idea for another book, a novel, but I am still intimidated by the idea of narrative. At the moment I have three protagonists, with three timelines, so that I can chop it up. We’ll see where it goes. Finally, I have an idea for a film script set in Wales — I want it to be about female desire and longing.

Caragh Medlicott: Is it important to you that these stories are set in Wales?

Katy Wix: It is and it isn’t — it just happens because it’s the only childhood I’ve known. I started watching the BBC3 series In My Skin recently. It’s set in South Wales and I think that Kayleigh [writer Kayleigh Llewellyn] is really talented. When I was first watching it I thought — “why does this feel weird?” — and it’s because I’m not used to hearing Welsh accents like this, aside from in Gavin and Stacey, I’m not used to hearing it played straight. I was speaking to the comedian Kiri Pritchard-McLean the other day, I went on her radio show, and she was saying that the writing in Delicacy felt really Welsh at times. Like it had this sad poetry to it — almost like standing in the rain somewhere in Wales. I like that — I think that’s nice.

Delicacy by Katy Wix is available now from Headline Publishing Group.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.