Ahead of Music Theatre Wales’ homecoming on Tuesday 8th October 2019, David Truslove travelled to ROH’s Linbury Theatre for a performance of Gerald Barry’s The Intelligence Park.

Last week at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre, Music Theatre Wales and the London Sinfonietta jointly presented Gerald Barry’s The Intelligence Park, an anarchic opera which first saw the light of day nearly thirty years ago when it was premiered at London’s Almeida Theatre. I came away from this heady experience bemused and exasperated, yet oddly drawn to a work that seems to be, in its absurd iconoclasm, the Classical equivalent of Punk Rock. Its surreal world is compelling, and so too virtuosic performances from an excellent cast who responded to the work’s maverick demands – summarised by conductor Jessica Cottis as “exquisitely difficult” – as if to the manner born. To memorise conventional melodic contours with regular metres is one thing, but to learn lines with counter-intuitive word accentuation and pitch contours resembling a financial crisis chart is no mean feat.

The Intelligence Park is the first of Barry’s six operas, yet despite its composer having “no fixed idea” about what the work is about, it has a life-force of its own. At its 1990 premiere, Michael McCarthy, Artistic Director to Music Theatre Wales, found it “thrilling but bizarre. It felt like this music had arrived from outer space”. Clearly transfixed by this Irish composer (born 1952), McCarthy believes it “is a work of such an extreme nature, dramatically and musically, and of such originality that it felt like the sort of piece Music Theatre Wales should be doing”. As an evangelist for new music he considers there’s “an audience out there hungry for challenge, engrossing intellectual exercise and musical inspiration”. Well, there’s always going to be a market for off-the-wall capers such as The Intelligence Park, and if last week’s niche audience was gripped by the performance, they might have been at a loss to follow the notion of a deconstructed opera bringing together fantasy and reality in themes of obsession, incapacity and betrayal.

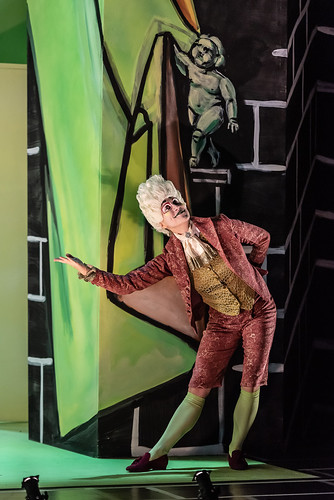

Vincent Deane, the librettist, sets the opera in Dublin in 1753 to which Director and Designer Nigel Lowery conjures a toy theatre comprising roughly drawn flats that he describes as “messed-up Baroque”. The work concerns an opera composer, Robert Paradies (Michel de Souza) suffering from writer’s block. His intention to marry Jerusha (Rhian Lois), the daughter of the wealthy Sir Joshua Cramer (Stephen Richardson), comes adrift when he finds himself attracted to her singing teacher, the Italian castrato Serafino (Patrick Terry) whose own interest in her – based on the real-life exploits of the castrato Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci – brings about a typically theatrical love triangle and gives rise to scenes of comically-staged intercourse. Other characters similarly attired in period costume and adorned as painted caricatures include Paradies’s companion D’Esperaudieu (Adrian Dwyer), Faranesi (Stephanie Marshall) and a row of stuffed dummies representing Dublin society interested only in excessive eating and playing cards. There’s also cameo appearances from a Grim Reaper and a leather-clad dominatrix!

So far so straightforward, but the text (bearing some kinship with James Joyce and generously interleaved with Italian) is ludicrously dense and its wilfully angular word setting, notwithstanding a persistent syllabic declamation, conspires to bury whatever fleetingly melodic lines occasionally emerge. Rare moments of pure lyricism are virtually lost within a welter of vocal acrobatics underpinned by a surfeit of wind and brass which rhythmically shadows the voices. It’s as if Barry has taken a wrecking ball to conventional vocal style and while Stravinsky’s neoclassical Rake’s Progress famously transforms 18th century mannerisms into something clearly still recognisable, Barry reboots and distorts the world of Handel to leave a scattered debris of musical ideas that require forensic scholarship to unravel them. This would all be less irksome if the words could be heard and the need to read the ceiling-high surtitles avoided especially when Faranesi declaims “But he must craunch the marmoset”. That said it was a pleasure to follow the lines of Cramer’s supper ‘aria’, “Soup enough to swim in; huge swinging tripes and trillibubkins”.

Singing and acting is consistently impressive across the board and among the principals Brazilian baritone Michel de Souza commands our ear, Stephen Richardson brings gravitas to Sir Joshua Cramer (reprising this role from its original performance), counter-tenor Patrick Terry sings with limpid beauty, Pontrhydygroes-born soprano Rhian Lois adds sparkle and stratospheric agility and tenor Adrian Dwyer sharply focused declamation. In the pit, the ever-versatile London Sinfonietta, under the firm baton of Jessica Cottis, dazzle with their efficiency and confirm Barry as a composer of formidable talent and originality. Be prepared when it comes to Cardiff on Tuesday 8 October to be mystified by this manic enterprise, but you’ll be sure to come away transformed.

Robert Paradies – Michel de Souza

D’Esperaudieu – Adrian Dwyer

Sir Joshua Cramer – Stephen Richardson

Jerusha Cramer – Rhian Lois

Patrick Terry – Serafino

Stephanie Marshall – Faranesi

The London Sinfonietta

Jessica Cottis – conductor

Nigel Lowery – Director & designer

Music – Gerald Barry

Libretto – Vincent Deane

You might also like…

David Truslove travelled to Covent Garden to witness Tosca, the latest production from the Royal Opera House featuring Bryn Terfel, Kristine Opolais and Vittorio Grigòlo.

David Truslove is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.