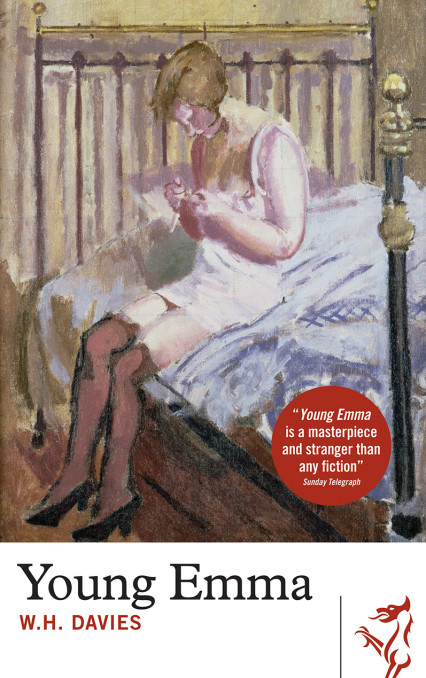

Gary Raymond on the 40th title in the Library of Wales Series, Young Emma, the ‘lost classic’ of WH Davies, not published until 40 years after the author’s death.

There is a danger with Young Emma that the story outlining the journey of the book from pen to print could come to outshine the book itself. In 1924, W.H. Davies wrote to Jonathan Cape, his publisher, that he was working on a new book but that it would have to be published anonymously – ‘It frightens me how it is done,’ he said. The story of Davies’ encounter and eventual marriage to young woman at a bus stop and the ensuing dramas, was committed to paper with unflinching honesty by Davies. When it was finished, he and Cape indulged in a little toing and froing and eventually Davies decided that the book could not be published. Davies had decided that so honest and raw were the details of the story that, as she was thirty years his junior, he could not commit her to a life of notoriety in the decades after he (and Cape) had left this mortal coil. Davies had read the manuscript to Emma, a simple if charming country girl, someone who it is clear from the book had no head for literature, and she was ‘very much alarmed by it’. And how alarming it must have been to have sat and listened to your character relayed back to you in Davies’ sardonic, self-involved prose. No doubt the arguments, musings and conversations that went on around the manuscript – all held by men at least twice her age – would have alarmed her just as much. It is perhaps singularly remarkable that the book was not published until after her death in 1979 (Jonathan Cape first published Young Emma in 1980, a full forty years after Davies had died).

By all accounts, everybody who came across the manuscript in those days when Davies was deciding what to do with it, thought it was a magnificent thing, rich and pure and unique. George Bernard Shaw, first to champion Autobiography of a Super-tramp with a forward on its publication, called it an ‘amazing document’ (although he advised aginst its publication, for Davies’ own sake). Cape was keen to see it out. But in the end Davies pulled the plug, and gave ever-so-slightly ambiguous instruction for the manuscript to be destroyed (destroy the manuscript ‘…as soon as you like.’) Cape erred on the darker side of ambiguity and put the m/s under lock and key, where it was ‘forgotten about’.

The real tug in this contextual question perhaps tells us more about WH Davies than the book itself, which is often discomfortingly self-aware in its prose. Davies frequently refers to his position as a celebrated outsider of literary London – but most certainly celebrated he was – and comes back again and again to the fact that he was far from naturally aligned with the artists with whom he often found himself socialising. Many of these artists would undoubtedly have had little trouble in masking into fiction such stories as we find in Young Emma, and of course in the case of the Bloomsbury lot this would move further to mythologising. Scandal would not have been tolerated, of course, as Roy Campbell found out when he was ostracised for his lampooning of the literati in his Georgiad poem. But scandal was largely a fluid term to the writers Davies knew,and a term of their own definition. The thing that really stood in his way however, was his class; George Bernard Shaw understood that when he advised that although the book is a masterpiece it should not be published during the life times of either Davies or his wife. Shaw notes in his advice to Cape that publication may ‘do him [Davies] harm’ and anyway ‘what right has he to give away his wife?’

So the book Young Emma, inside and out, is a fascinating document of the times, there is no denying it. But what of that inside? Is it a masterpiece?

The simple answer – and you have to really push for simple answers always with Davies – is that it is not a masterpiece, but rather a significant curiosity written by one of the most popular literary figures of his day. The book professes throughout to be about this young woman who stole his heart, but it is from beginning to end a book about the author, a book about men. This is not Flaubert or Tolstoy, and Emma is neither Madames Bovary or Karenin. Davies’ insight is almost always turned back toward himself, whereas Emma’s story, although told with sincere compassion, is narrative and presumptive. We like Emma in the same way we like innocence, country girls, a bit of peril and a happy ending. But it is Davies we get to know. Perhaps had Davies been a novelist and this book been a novel it might have given him the license to explore further.

What Davies is a master of, as you can see in his other works of prose and his poetry, is of structure and voice. Young Emma is structured like a novel, paced perfectly, the development of the plot unfolding with a careful hand. Had it been published in 1924 it may have become part of any conversation that brought up Bartleby the Scrivener or even Metamorphosis. There is a similar claustrophobia to Davies’ lodgings as we feel with Bartleby’s office or Gregor Samsa’s apartment (and perhaps even Samsa’s metaphor is in the region of Davies’ reality). You feel the same smoke in the air, the same damp corners and cobbles as you do in these great works. And Young Emma is extremely funny, too. WH Davies may be self-involved but he cannot be said to be guilty of taking himself too seriously.

Davies’ voice is attractive because it is so unusual, so untarnished by sophistication, and this may perhaps account for many aspects of Davies’ ‘otherness’ – something Bernard Shaw was attracted to. You could argue Shaw appreciated a social experiment related to his Pygmalion (1913) in Young Emma – the parallels are obvious, only in this facsimile Henry Higgins is an ex-tramp. What is more likely is that Shaw had sympathy for Davies’ style and philosophies as they fell much into his Ibsenist outlook. The ideas Shaw recorded in his essay ‘The Quintessence of Ibsenism’ (1890), are stunning in how germane they are to Davies’ writing: ‘out of a thousand persons there are 700 philistines, 299 idealists, and only one lone realist.’ In WH Davies he saw the one realist, the figure who went about life insisting on the removal of masks. Young Emma is an intimidatingly mask-less book (too intimidating even for its author). To this effect, all other literature of the time – the mythologising of things that were real – were exercises in the ideal. So in this sense, in the purest sense, Young Emma really is a formidable work.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, editor and broadcaster.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.