To mark the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, our writers recall their memories of life under the rule of the inimitable Bard.

Mark Blayney

Before I was a writer I was an actor. The most enjoyable role in this short career was as Gloucester in King Lear, a touring production that had one wooden chair as its only prop. We had an enthusiastic ensemble of actors, most of us recent graduates, and a powerful, eccentric leading man. Our King genuinely believed that the aliens were amongst us, and it was only a matter of time before they revealed themselves. We’re still waiting, but even now I do occasionally look around in Tesco and think, was he right all along?

There were great hopes for this production, which was meant to go overseas and tour Paris, Germany, Bosnia and the US. In the event, we didn’t get further than Norwich, but after each performance, as the husband-and-wife director and stage manager packed the precious chair away into the minibus, we dreamed of our future success and observed how the world really was our oyster, populated, perhaps, by some aliens.

There were great hopes for this production, which was meant to go overseas and tour Paris, Germany, Bosnia and the US. In the event, we didn’t get further than Norwich, but after each performance, as the husband-and-wife director and stage manager packed the precious chair away into the minibus, we dreamed of our future success and observed how the world really was our oyster, populated, perhaps, by some aliens.

It tested us physically. Most of us had at least two roles (the Fool was played by each of us in turn) and the actor playing Edmund, slim to begin with, was positively skinny by the end of it. This was mainly because he spent much of the evening running back and forth behind the back curtains, getting changed en route out of Edmund’s clothes to become Edgar a few seconds later from the other side of the stage. This, when we were in different theatres each time, gave him some problems. I often heard the thump and cry of muted pain as he found a new block of steps or obstacle to bump into backstage.

I had my first stage kiss, which, being young, I pretended not to be excited about. And as Gloucester I got blinded halfway through. If the set was minimal, the attention to detail here was the opposite. Each night a new set of blood bags was made up, so that when Goneril and Regan straddled me to gouge my eyes out, large quantities of thick, viscous blood were punctured in my face. The results were simple and distressing. I could hear (if not see) the gasps from the audience, and one night my mum came to watch and looked very pale afterwards. To this day, whenever I think about King Lear I can smell the mix of stale raw egg, cochineal, cornstarch and whatnot. One night I nearly threw up whilst being escorted off. But one is a professional, darling, and I managed not to cover the stage in vomit, although this perhaps might have added some noir-ish grit to the performance.

I don’t miss acting, but I do miss how it informs your relationship with the author. You get to appreciate Shakespeare far more from performing than from reading it. The lines are easier to learn than expected, because of their rhythm, and you feel a connection to the author that’s almost mystical; you hear him speaking to you. The recent news that students will no longer have to go to see live drama as part of their GCSE is concerning; but as long as they still stand up, act it out and use a wooden chair for a prop, they’ll be getting that experience.

Barbara Michaels

My iconic Shakespeare Moment was seeing Robert Helpmann perform Hamlet with the RSC at the Royal Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-Upon-Avon. The play was performed with a minimal set – unusual back in 1948. Dressed in a white open-necked shirt and black trousers, Helpmann, who made his name as a ballet dancer renowned for his sympathetic interpretation and elegance of movement – sat on a three-legged stool centre front on an otherwise bare stage. As he started speaking the famous soliloquoy “To be or not to be – that is the question” each word was like an icicle, sending shivers down the spine. You could have heard a pin drop. I have seen several actors perform that role since then – notably David Tennant, who came a close second – but never a performance that moved me like that one long ago.

My iconic Shakespeare Moment was seeing Robert Helpmann perform Hamlet with the RSC at the Royal Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-Upon-Avon. The play was performed with a minimal set – unusual back in 1948. Dressed in a white open-necked shirt and black trousers, Helpmann, who made his name as a ballet dancer renowned for his sympathetic interpretation and elegance of movement – sat on a three-legged stool centre front on an otherwise bare stage. As he started speaking the famous soliloquoy “To be or not to be – that is the question” each word was like an icicle, sending shivers down the spine. You could have heard a pin drop. I have seen several actors perform that role since then – notably David Tennant, who came a close second – but never a performance that moved me like that one long ago.

Gary Raymond

I’m sure I let out a whoop the first time I saw Shakespeare in Love and the urchin John Webster, petting his rat, tells Tom Wilkinson’s Hugh Fennyman that he likes Shakespeare’s earlier plays, the violent ones, the ones with all the blood in them. In Shakespeare in Love, which all but the most hard-hearted snobs will remember builds up to the debut of Romeo & Juliet, this Stoppardian in-joke gives a shout out to Titus Andronicus, and to the gory Jacobean revenge tragedies that came soon after Shakespeare’s reign. We studied The Duchess of Malfi for A-level, and that twisted nightmare of asylum grief spoke more to the 16 year-old me than Shakespeare had done. I was with Webster all the way, and I felt myself nodding along with him: Titus Andronicus is my favourite work of the Bard.

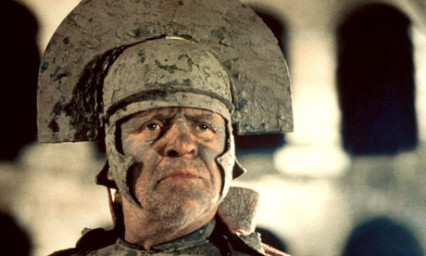

The reasons are many – I revel in just how bonkers it is! It is a horror movie. And Julie Taymor’s film version, with Anthony Hopkins in the title role, must be the most accurately insane version of any Shakespeare script put to film. I also love what it has influenced, most notably, Vincent Price feeding poodle pie to Robert Morely in every theatre critic’s favourite film, Theatre of Blood.

The reasons are many – I revel in just how bonkers it is! It is a horror movie. And Julie Taymor’s film version, with Anthony Hopkins in the title role, must be the most accurately insane version of any Shakespeare script put to film. I also love what it has influenced, most notably, Vincent Price feeding poodle pie to Robert Morely in every theatre critic’s favourite film, Theatre of Blood.

In Titus Andronicus there is a sense of everything unleashed. In MacBeth, another favourite for similar reasons, hell and damnation are always courted via spectral, hallucinatory conduits. Titus has no such veils. Rape, barbarism, debauchery, mutilation, incest, murder of every kind – we are down deep here. And much of it is not about ambition or politics, as with many of Shakespeare’s brutal plays, but it is about survival. Aaron may be one of the Bard’s characters who takes a moment to tell us he his bad for the sake of it, but much of the mayhem is sparked by Tamora’s ruthless wish to survive her capture, as well as avenge her capture. There is something more Greek about Titus than any of Shakespeare’s other plays.

The first time I saw it, me and few friends crammed in to Bath’s Theatre Royal for a matinee (always see matinee’s of Shakespeare to be sure of giving yourself an absolute minimum 3 hours pub discussion time afterwards). The defining moment of a brilliant production, and the moment that has been retold at many a party in the 15 years since, was when Titus offers Aaron his severed hand as proof that he and Queen Tamara are even (it is a ruse, of course – there is quite the bloody climax to come). Throughout the play me and my friends had been wryly smiling at the two old women behind us, the complete cliche of gummy sweet-sucking, wrapper rustling and non-whispered commentary throughout. The climax, less bloody, of this play within a play (something of The Two Ronnies about it) was when Titus cut off his hand and, stunningly choreographed, the hand flew into the air for Aaron to catch in a paper bag. “He put it in a baaaaaagggg!!!” screeched one of the old women behind us, loud enough for the entire theatre to hear it. What else could you say? He had indeed put it in a bag.

Nicola Ann Roberts

I never really wanted to become a teacher.

I’d seen my own English teacher’s fervor for the subject dissipate under the stress of exam results, paperwork and lesson planning. I couldn’t imagine a worse fate, until I returned from a year and a half round-the-world trip and I had nothing to do. I was broke, living at home and nursing the same issues with my dad that existing on different continents had, for a while, alleviated. I was desperate to go abroad again and I realised that teachers were needed everywhere, even in the furthest reaches of the world. So I Googled Katmandu and accepted the very generous £10,000 offered by the government to train as a secondary school English teacher. After all, Those who can, teach.

I didn’t know if I could but that was fine, I’d take the money and run.

Ten years on, I’m still in Wales and I’m still an English teacher. And the reason? Shakespeare. In fact, I can pinpoint the exact moment when I discovered that not only am I good at my job, but that I enjoy it.

It was my first term as a newly qualified teacher. I’d been teaching Romeo and Juliet to the kind of Year 9 class that dreams are made on. The students were bright, creative and fearless and had never truly encountered Shakespeare before. They knew of him, but none of the students had knowingly spoken his words. I tend to romanticise the moment I decided that teaching was for me. I always remember the sun streaming into the hall and the sense of time at a standstill. But in reality, it was mid-November and the sun probably hadn’t made an appearance for months. It would have been cold in the hall and the students, in their costumes, would have been shivering. Groups of shy thirteen year olds were bunched together with their scripts, each with a different section to perform. It allowed me a wide, sweeping shot of the scene and as I moved from a dog of the house of Capulet moves me to did my heart love till now? I felt a sense of achievement that I had never felt before. I had transferred my love of Shakespeare and it felt like a gift. By the time I got to Romeo, Romeo wherefore art thou Romeo? I had stopped for a moment and I remember thinking, right then, when the sun wasn’t shining through the windows and Juliet’s costume didn’t quite fit the girl who would one day become a Shakespearean scholar, that I loved my job.

It was my first term as a newly qualified teacher. I’d been teaching Romeo and Juliet to the kind of Year 9 class that dreams are made on. The students were bright, creative and fearless and had never truly encountered Shakespeare before. They knew of him, but none of the students had knowingly spoken his words. I tend to romanticise the moment I decided that teaching was for me. I always remember the sun streaming into the hall and the sense of time at a standstill. But in reality, it was mid-November and the sun probably hadn’t made an appearance for months. It would have been cold in the hall and the students, in their costumes, would have been shivering. Groups of shy thirteen year olds were bunched together with their scripts, each with a different section to perform. It allowed me a wide, sweeping shot of the scene and as I moved from a dog of the house of Capulet moves me to did my heart love till now? I felt a sense of achievement that I had never felt before. I had transferred my love of Shakespeare and it felt like a gift. By the time I got to Romeo, Romeo wherefore art thou Romeo? I had stopped for a moment and I remember thinking, right then, when the sun wasn’t shining through the windows and Juliet’s costume didn’t quite fit the girl who would one day become a Shakespearean scholar, that I loved my job.

I never really wanted to become a teacher. But standing in that dim and cold hall, enveloped in the warmth and luminosity of Shakespeare’s language, gave me the distant lands I’d been hankering for.

Dai George

I’ve been lucky enough to catch some great performances, from Ian McKellen’s scabrous, sorrowful, shockingly full-frontal Lear to Coriolanus staged by National Theatre Wales in a disused airport hangar. Sheen as Hamlet, Matthew Rhys as a sultry, muscular Romeo: just the Welsh top brass playing title roles could fill a few paragraphs now I think of it. In amongst the gems there’s been some dross, usually the result of fussing about authenticity or else caring too little about it in the misguided pursuit of relevance.

Striking that balance between a respect for the plays as artefacts (contemporary to Shakespeare’s original audience) and artworks (contemporary to our moment) will always be the challenge facing any modern production. It seems inevitable that we should get that balance wrong from time to time, because god knows Shakespeare didn’t work in some vacuum of divinely ordained perfection. He wrote quickly, for the talents of particular actors, in response to the books he read and the events that shaped his world, sometimes in direct collaboration with other writers, and always with at least one eye on the gate receipts.

Nobody has taught me more about this febrile, endlessly fascinating context than James Shapiro. At first the teaching happened remotely, with me wolfing down his 1599 towards the end of my first year at university, in the Easter holiday following a dry ‘Approaches to Shakespeare’ module. 1599 gave me the raw, pulsating story of a year in Elizabethan England side by side with a deep reading of Hamlet, the one animating the other. It was my real education in Shakespeare.

Imagine, then, the excitement I felt when three years later – now at Columbia University – I skimmed the course directory and found a class with Prof Shapiro on 1606 and King Lear. I applied, more in hope than expectation: being a mere creative writing student, I expected a polite rebuff from this world-class scholar, as he protected his no doubt vastly oversubscribed course for the benefit of early modernists. Imagine my shock, then, when he emailed back with a warm welcome to the fold, signing off with a simple ‘Jim’.

I can safely say that this stroke of right-place-right-time good fortune has changed the course of my life. Unusually for celebrity academics, Shapiro as a teacher embodied all the qualities of Shapiro as a writer – stimulation, rigour, generosity, with the added bonus of a bone-dry Brooklyn drawl and a sense of humour to match. I remember him coming to class with an overflowing brown paper bag of bagels under one arm and a flask of coffee in the other, ready to give us sustenance for an hour spent discussing the Porter’s scene in Macbeth and the kaleidoscopic meanings of one word, ‘Equivocation’.

Shakespeare was a playwright (duh) so it seems somehow wrong to choose a memory of his work that takes place in the classroom not the playhouse. All I can say is that the classroom’s an exciting place when it has Jim Shapiro in it. Moreover, it’s thanks to the art of scholars like Shapiro – and there aren’t many of them to the pound – that we can go to a performance of King Lear today, confident that what we see onstage forms a link in a chain stretching back to its first audience, and what they would have thought and felt when watching it for the first time in 1606.

Cath Barton

Like so many others, I experienced Shakespeare’s plays only in gabbled versions when I was at school. I couldn’t understand them at all. But in due course I saw and heard Shakespeare played well, with proper attention to the cadences of the language. And while I now appreciate and love the beauty of his language, it is the characters in his plays who he referred to as the “lighter people” for whom I have the greatest affection. Sir Toby and his late-night carousing friends in Twelfth Night, the rude mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and so on.

A good many years ago I had a partner who was an amateur actor. He played a lot of Shakespeare. One summer we were holidaying in Provence and he was preparing to play the twin roles of Angelo, the Duke’s deputy, and Pompey, the pimp, in Measure for Measure. We sat on our balcony, glasses of wine in hand, and I heard his lines. The play was new to me. We got to the scene where Pompey is being questioned by Angelo’s man about his supposed misdemeanours. Reading ahead I saw the following lines coming up:

Escalus: Come you hither to me, Master tapster. What’s your name, Master Tapster?

Pompey: Pompey.

Escalus: What else?

Pompey: Bum, sir.

Escalus: Troth, and your bum is the greatest thing about you, so that in the beastliest sense you are Pompey the Great.

I dissolved into giggles. Actually, I couldn’t speak. Bum – a Shakespearean word! This no doubt sounds pretty childish, but the serious point is that the business with Pompey is an example of Shakespeare’s genius at drawing people into the serious content of his plays. Measure for Measure deals with issues alive in politics now. Pompey is one of Shakespeare’s “lighter people”. His supposed sins are at least out in the open. Unlike those of the much more sinister Angelo. To see the two played by the same actor, as I then did over many performances, was actually spine-chilling – smile-wiped-off-face material.

My relationship with the amateur actor is long over. My relationship with Shakespeare is alive and well.

Frances Spurrier

If I have a single bard-related memory, it is of the sinking feeling that the mention of him always brings even – I am ashamed to admit – these days. Recently I tried to sound enthusiastic when a friend suggested a visit to the theatre at Stratford. But there it was again, the same old dread. So much death; so many coincidences; too many shipwrecks and not enough horses.

It started as so many Shakespeare memories do, with a bad experience of being force-fed Macbeth and his odious Lady at school. If you attended school in the United Kingdom at the time when I did (full many a glorious morning have I seen) the English curriculum was bard-intensive. I laboured through the wretched ‘out damned spot’ speech for GCSE along with the best of them.

Yet I am not a complete Shakespeare heathen. Who would not want to be shipwrecked and land on an enchanted isle? The only drawback would be having to cope with Prospero and his annoying sprite. I have been awestruck by David Tennant’s Hamlet. I have seen some of the great Knights of the British theatre go mad on stage and I have wept with Cordelia. I have watched Joseph Fiennes and Gwyneth Paltrow rollicking across the big screen in search of the bard – or at least his sex life. I have adored Christopher’s Wheeldon’s ballet of The Winter’s Tale and am plotting to see it again.

I can recognise Shakespeare’s all-encompassing influence on every aspect of the literature and culture of his country. Yet somehow I still connect him with that sense of worthiness and duty. The school hangover. “And you call yourself a poet?” I hear you inhale sharply. “The sonnets! Surely … at least … the Sonnets!” Well, yes, let me not to the marriage of true minds admit visions of Kate Winslet in Sense and Sensibility.

Despite all the above, I am very excited and consider myself fortunate to be reading Sonnet 26 as part of the Winchester Shakespeare 400 celebrations this month. Doth that makest of me an hypocrite? When the organisers emailed round for volunteers apparently there were hundreds of people wanting to read Sonnet 18 (‘Shall I compare thee…’) and Sonnet 116 (‘Let me not to the marriage…’). An equitable distribution needed to be made so that there would be a reader for each sonnet, rather than a hundred readers for one sonnet and no-one for the rest. But then that’s the bard for you. The great equalizer.

Adam Somerset

I had it lucky with Shakespeare; the introduction never came by the pedagogic route. When that time, inevitably, did arrive and our English master handed out twenty-six tired copies of Macbeth to his class of fifteen year olds I had already had a long acquaintance with Will of Stratford. That familiarity had three different strands.

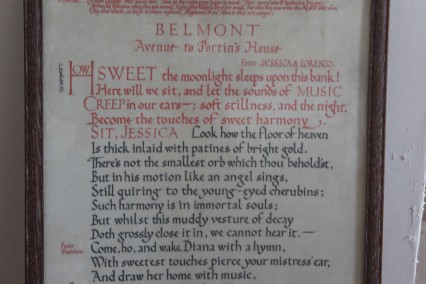

For a start he was right there, close to our front door. My grandparents, late Victorian, had siblings galore, at least two dozen great aunts and uncles, bewildering to a child. The liveliest had broken out and taken a training in art. Becoming a master calligrapher her wedding gift had been a speech from Shakespeare. I doubt if I ever read it but at a height of five foot it hung permanently next to the front door.

For a start he was right there, close to our front door. My grandparents, late Victorian, had siblings galore, at least two dozen great aunts and uncles, bewildering to a child. The liveliest had broken out and taken a training in art. Becoming a master calligrapher her wedding gift had been a speech from Shakespeare. I doubt if I ever read it but at a height of five foot it hung permanently next to the front door.

Shakespeare was literally a part of the furniture.

That hall and that speech from The Merchant of Venice were located fourteen miles from the Avon. Stratford was thus never a place for reverence and pilgrimage. Nearby Charlecote Park was first a place for play and secondly a place where the young pre-writer had supposedly gone poaching.

The Avon itself was site for a regular hour’s boat-hire and messing about on the river. Once outside the theatre mid-river my father pointed upward. On a high-up galley a Sultan in full regalia, in retrospect most likely a suitor for Jessica, was taking a breather during a Saturday matinee. The town’s memorial monument was familiar, a place for a game of tag rather than literary homage. The characters had their stories – Prince Hal trying out the crown before the monarch had even died, Lady Macbeth forever trying to cleanse her hands of blood. These were good stories for kids.

Shakespeare was never text on a page. He was action. Admittedly he came with a few words but the school-trip audience member could always tune out the speeches and await the next action. Puck and Oberon spun plates and conversed on trapezes. A thirty-six year old Ian Richardson was a nasty Angelo one year, a battling, contemptuous Coriolanus the next. Richard Johnson was Mark Anthony to Janet Suzman’s full-throttle Cleopatra.

These were big shows. By the grim seventies Terry Hands had to make do with a cast of a mere twenty-five where Peter Hall in 1964 had fifty for his Henry V. Hands’ Henry V played London and internationally to acclaim. Its impact was tremendous. I even heard two theatre old-timers talking about it with rapture in Aberystwyth’s Arts Centre in the autumn of 2015. Those with a penchant for the waggling of cameras who like to spout on theatre’s ephemeral nature should pause, look and listen. For myself that Henry of the late Anthony Howard was of such an impact that I have never felt the need to see the play again.

If there is a moral to be had here it must be that Shakespeare is best kept well away from the printed page. If children have to do him, and I suppose they must, then let actors be the conduit. Downplay the awe and heritage and give the kids what they like, blood, battle and malice. Add too that George R.R. Martin’s naming of Stark versus Lannister is pure linguistic homage to York versus Lancaster.

Glyn Edwards

Crouched in the gloom at the side of the curtainless stage, the three bodies were silver-skinned and rag-wrapped; one woman was shaven-headed, one woman was, in fact, an elderly man, one woman was revealing more flesh than anyone in my pre-GCSE class (in their pre-internet schooling) had ever witnessed. The three witches were immediately intimidating; to a group of boys who had never been to theatre before, they were formidable.

No pupil wanted to be shepherded by the elderly stewards to the front of the theatre and none wanted to bookend the draughty first row. My first experience of Shakespeare was to sit directly under the glare of the three witches before Macbeth began at Mold’s Theatre Clwyd and, as the school bus had arrived thirty minutes early, my ordeal of eye-contact avoidance began early.

The witches lurked stage left throughout the play, haunting Macbeth from his periphery. They possessed during the interval and even remained to jinx the audience as we left; I am fairly sure that, while the rest of my class echoed bad Taggart impressions and slugged No-Frills Cola, one of the witches was stood in the aisle next to me on the coach, then followed me home in the rain.

The witches lurked stage left throughout the play, haunting Macbeth from his periphery. They possessed during the interval and even remained to jinx the audience as we left; I am fairly sure that, while the rest of my class echoed bad Taggart impressions and slugged No-Frills Cola, one of the witches was stood in the aisle next to me on the coach, then followed me home in the rain.

My son repeats ‘shakes peer’ rhythmically in the café, like we have rehearsed it for the Americans who are noisily debating whether to stay and order. He colours the playwright’s face on a brochure, shading the pupils, rainbowing the lank hair. We tell him that Shakespeare spelled his name six different ways and try to show him, but he will not forsake the crayons and begins instead to write his own: the hooped ‘A’, a hangman’s ‘r’, a wide, flamboyant ‘t’, then, realising he is choked of space, doubles back, adds a ‘h’, ‘u’ turns and slots the ‘r’ between earlier letters. ‘Shay kspere’, he says, ‘shhhhake speer’.

He sounds the name as we thread the narrow corridors of Shakespeare’s Birthplace. The tiled floor of the living room is as cracked as the back of an old glove, the button-sized windows look out onto the courtyard where a seam of Chinese tourists are being led by an actor playing a lute. Over the empty beds, the empty fireplaces, the empty cribs, he says, ‘Shakesp ear’ and seems to inhabit the place.

In the garden, he is finally stilled. It is beginning to get cold and there is drizzle hiding in the late afternoon; the blossom cloaking the cherry trees is a reminder that it is still Easter. A lady in a cloaking, green dress covets his attention and earns it with her playful accents, ‘Double double, toil and trouble,’ she begins, casting her arms, stretching her fingers.

‘Double double,’ he mimics.

The actress plays all three parts and bewitches him. He is silent for so long on the winding walk back to the hotel that we know he is trying to make sense of it all, that he is trying to give voice to the changes happening to his thoughts, that he is rapt withal.

Elin Williams

Shakespeare and I have always got on. I was good at English at school, average at University and now I teach others how to do the English. Bill and I had a brief falling out in 2010 when I didn’t like a lecturer at University so couldn’t take the Late Plays Module but asides from that, it’s been smooth sailing. I’ve studied most plays, taught three or four, seen countless performances, but there is one memory that really endures.

I was nineteen. I had decided that I was going to make new friends in Cardiff and be brave, so I was going along to the open auditions for Cardiff’s drama society, Act One. I was probably wearing something awful that I thought made me look interesting and quirky. In fact, I’ve had a flashing recollection whilst writing this that I was wearing legwarmers. Yep, I was, I was wearing legwarmers. I had decided to audition for the musical, Footloose (God only knows why. It must have been the leg warmers) and the Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing.

The corridors were littered with Act One veterans rehearsing audition pieces. What the hell was I doing? Did I really think that my legwarmers and I stood a chance at getting a part against these people? I wanted to be sick, but instead, I queued up, signed my name, got a script and scanned it quickly. I was good at deciphering Shakespearean language quickly, but suddenly the words were swimming in front of me. What possessed me to enter that audition room I will never know, but I did. Me and my legwarmers against the world. (For a detail only remembered whilst writing this, my legwarmers have become a notable feature in this piece haven’t they?)

The corridors were littered with Act One veterans rehearsing audition pieces. What the hell was I doing? Did I really think that my legwarmers and I stood a chance at getting a part against these people? I wanted to be sick, but instead, I queued up, signed my name, got a script and scanned it quickly. I was good at deciphering Shakespearean language quickly, but suddenly the words were swimming in front of me. What possessed me to enter that audition room I will never know, but I did. Me and my legwarmers against the world. (For a detail only remembered whilst writing this, my legwarmers have become a notable feature in this piece haven’t they?)

I faced a panel of about four or five people. I did the audition. I don’t remember it. I do remember getting a voicemail asking me for a call back from my now good friend Matthew King. I also got a call back for Footloose, but the less said about that, the better. I went along to the call back and finally received a phone call telling me that he and his co-director and then girlfriend, now wife, would like me to play all the odd parts. I was a messenger, a sexton, Ursula and a Watchman, I think. It transpired they liked my silly Welsh accent.

During the rehearsal process I kept acquiring new parts because (this is a direct quote from Matthew King, the director) “We didn’t realise you could actually act.” I made so many friends during the rehearsal process, had an amazing time and thoroughly enjoyed the whole experience. The type of enjoyment that when it’s over, you don’t know what to do with your life because you’ve been consumed by it. The production reminded me of the genius of Shakespeare. The play was genuinely hilarious, but not because of us, because of the writing. The show really embraced how entertaining Shakespeare was and would always be. We had so much fun with it, it wasn’t taken too seriously and the result was an unforgettable production for all involved.

I’ll never forget the opportunity given to me by Matt and Ruth. Without Act One, my time at University would have been completely different and a LOT less fun. I met some of my very best friends in that society, wrote and directed my own plays, acted in fantastic productions, partook in some highly competitive fancy dress and even took a show to the Edinburgh Fringe festival. Act One made my University experience, and it was all down to a Shakespeare play and one chance given to a girl with her legwarmers and her silly Welsh accent.

Nigel Jarrett

In a different existence I’d live and work in Stratford-Upon-Avon so that I could easily get to all the affordable RSC productions; in fact, I’d make sure I could afford them. It would be my reason for being there. Despite what would be going on in contemporary theatre and in the re-defining of classics from eras other than the Shakespearian, I would consider what went on at the company’s main house and its intimate annexe, the Swan, central to what I understand by theatre and theatrical thrill.

In any case, I’ve seen many great productions and performances, especially in the 1980s: Zoë Wanamaker as Viola in Twelfth Night (1983), Michael Pennington in the title role of Hamlet (1980), Sinéad Cusack as Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing (1982), and Antony Sher in the title role of Richard III (1984), among others. I think Stratford offered me my first true theatrical experience. At the Swan, there was Middleton, Jonson, Congreve, Chekhov and, so far this year, Marlowe – plus Shakespeare, in a Swan-tailored production of Henry V by Gregory Doran.

It would be idiotic to state that everything at the RSC was always rosy. There’ve been highs and lows, though the 21st century up there seems to be glowing continuously. I recall one period when the verse-speaking wasn’t as convincing as usual, and lately Stratford has been no different from other theatres in having some actors almost whisper their lines, with the non-whisperers, the voice-throwers, being usually of the older generation and if men then men with beards. (My theory for the latter is that actors who spend time before the TV and film cameras forget that voice production in a theatre requires a different technique. I’m sure they’re aware of that but they don’t always heed it.)

It’s hard to see modern Stratford – the town, I mean – as anything more than a heritage site thronged with tourists. One does sometimes hear about another, more ‘colourful’ Stratford, perhaps one Shakespeare himself might have recognised, mutatis mutandis. One night, while walking from the main theatre after seeing Patrick Stewart as Prospero in The Tempest (Julian Bleach’s Ariel was the show-stealer), we witnessed a strange, almost theatrical sight, just yards from the pub where we were staying. We may even have been the first to observe something that in later months had became universally newsworthy: a pavement scrum of about twenty youths, boys and girls, consisting of two males brutally scrapping and an audience of eggers-on, their faces bilious with the neon light from mobile phones. They were filming and broadcasting the fight as it was happening. ‘Rude mechanicals on a night out’, one of us commented, with, it must be admitted, a detachment both ironic and slightly superior. Well, the theatre is not supposed to be an inviolable shrine, but theatregoers and the characters they go to watch do sometimes appear to inhabit different worlds at places like Stratford, especially the toothless characters who allowed Shakespeare to offer light relief.