Bianca Bellová was born in Prague and grew-up as the communist regime of Czechoslovakia began to fracture. This background provided the material for her first book, Sentimental Novel. She has since written four further novels and worked as both a translator and interpreter. The Lake won the Czech national Magnesia Litera Book of the Year Award and the European Prize for Literature. It has been translated into over twenty languages and is published by Parthian this month. Here, Glen James Brown interviews Bianca Bellová, prior to the UK launch at the Czech Embassy in London.

Glen James Brown: In previous interviews, you have mentioned the Borgesian Conundrum: You don’t know whether the author is creating the story or the story, the author. It reminded me of the novelist Elizabeth McKenzie’s views on inspiration as ‘fermentation’—memories and experience ferment in the subconscious and eventually bubble up to the surface in the form of a story. I’m interested in the position this puts you in when writing. Are there times when you, The Author, disagrees with The Subconscious on the direction of the story? Did that happen at any point when writing The Lake? And if so, how did you resolve it?

Bianca Bellová: Yes, an interesting question indeed. For me the best sign that I have written decent prose is looking back at it and wondering what the hell happened? . Where did all those words come from and who welded them together? Where was I? And then I remember vaguely how I tried to tame and drive those words in a way I deemed sensible. To me, writing is like marriage of this highly unpredictable call from the subconscious or whatever you want to call it which saddles you up – and the disciplined craft with which you somehow try to control that wild horse. The craft gets better with experience, but the madness of the inspiration is just as exciting every time. At some point you sense it quietly knocking of your minds door and the next thing you know is it has taken over and there is nothing you can do but to surrender to it. And it is actually the ultimate joy the author can experience, or at least for me it is. Like a privilege or grace which has fallen upon you.

My latest novel titled The Island is due out in March next year and those who have so far read it are rather puzzled: Where does it come from? It is so very different from the contemporary literary canon. It is set in the Middle Ages with a merchant for a main character who is travelling the world to put his conscience at ease, nothing could be further from my normal scope of interests, being a medievalist was never my ambition. And I could not tell you where the text came from. At the beginning of the pandemic I could not help thinking about the similarity with the plague epidemics. At that time, I was also reading the History of Death by Philippe Ariès and A Fantastic Bestiary for Travellers by Dominique Lanni, and all these sources somehow started blending together and, voilà, a year later, I end up choosing a cover design for a new book. A book that gave me a great refuge through the challenging times of the coronavirus years. I am sorry I talk about my latest work instead of answering your question; I am always most excited about the work I currently work on.

Glen James Brown: Nami’s journey through the novel in search of his mother feels archetypal. The landscape he moves through is fictional—almost Biblical at times—even though you must have drawn on your own experiences growing up under Eastern-Bloc oppression. Could you talk a little about your decision to locate the story beyond real-world geography?

Bianca Bellová: I am not sure I can answer this one precisely; you are presuming that I know what I am doing when I write which is – more often than not – not the case. You know what Marcel Reich-Ranicki said about writers – that they don’t understand literature any better than birds understand ornithology. In my case, it is more than true.

I guess I located it in an area you cannot find on the maps in order to avoid writing a documentary prose about Lake Aral, which was the source of my initial inspiration, just a couple of powerful photographs from the devastated land which was once a thriving community. And later on, I also found out that this vagueness allows readers from different parts of the world to relate to it, be it the people from the Baltics who have the similar experience with the oppression you talk about and a presence of a foreign military force like my country does, to readers in Japan with the aftermaths of Fukushima. But that was never a calculated plan.

Glen James Brown: Similarly, I felt like time itself was slippery. The Lake begins in a post-USSR landscape, but increasingly feels like a post-apocalyptic future where society and climate are about to collapse. Nami could be somewhere in the late 20th Century, the present, or a hundred years in the future. Would you agree? If so, what was your thinking behind this?

Bianca Bellová: Again, there wasn’t really any thinking or planning behind it but it is my belief that a reader gets a more satisfactory experience from reading when he or she takes part in the making of the story. When they have to put their imagination and own memories and images to work and co-create. Some reviewers bluntly described the novel as the story of the Aral Sea, yet another reader told me that it describes the atmosphere of the time when he was growing up in Poland in the 1980s. And I really like the fact that each reader gets their very own book and it is never the same for two readers. There is no right or wrong way of interpreting it.

Glen James Brown: I loved how sensory your novel was. You tell Nami’s story via his physical reaction to smells, tastes, cold, and other sensations. It is filled with blood, sweat, and vomit. Rashes and infections. I found this method of storytelling very effective, and was wondering why you kept returning us to the physical in this way?

Bianca Bellová: That again is quite an instinctive matter; it is the only way I can write. However, I recently read it in Mystery and Manners, the collection of essays and lectures by Flannery O´Connor where she actually strongly recommended to her students of creative writing to use the reference to the sensory experiences as a powerful tool to engage the reader. So, there goes the secret.

Glen James Brown: The Lake seems to tell us what might happen if we stop loving not just each other, but the planet itself. The world you depict in your novel can be incredibly brutal, but you do show glimmers of love and humanity that seem to say all is not lost. It’s a heavy question, but do you have hope for us as a species? If there is a way back from the brink for us, what might it be?

Bianca Bellová: I was never good at giving predictions or wisdom. I certainly do believe though that humanity has a very strong self-preservation drive and every action prompts a counteraction, so the harmful moves in the learning process are always replaced by an opposite effect – and then forgotten so that it can all start anew.

Glen James Brown: The Lake won the EU-Prize for Literature and has been translated into over 20 languages. Congratulations on it now being translated into English. What are your hopes for the book with English-speaking audiences?

Bianca Bellová: It is dream come true really as breaking into the English-written book market is such a challenge; a realm which is full of highly literate and sophisticated readers who could hopefully enjoy my writing. Other than that I have no other aspirations.

Glen James Brown: Finally, no writer works in a vacuum. What writers, artists—or anyone in fact—have inspired and shaped your own work?

Bianca Bellová: I wouldn’t know where to start really. There are two writers– Kazuo Ishiguro and Ian McEwan – whom I hold in high regard but the list would be endless and nobody likes reading lists. There would be Marguerite Duras on it, as well as Doris Lessing and Toni Morrison and so many others. One can always aspire to writing like someone else, but the truth is you can only ever write like yourself.

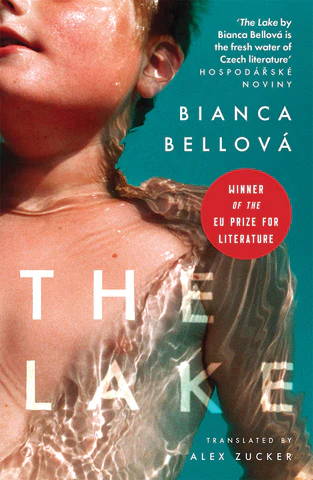

The Lake by Bianca Bellová is available from Parthian Books.

Glen James Brown is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review. His latest novel, Ironopolis, was shortlisted for both The Orwell Prize 2019 and The Portico Prize, and is available now from Parthian.