Cath Barton reviews The Golden Dragon, an opera by Peter Eötvös based on the play of the same name by Roland Schimmelpfennig.

A gorgeous, silken orange drape patterned with a golden dragon is raised. Members of the Music Theatre Wales Ensemble, sitting centre stage, are dressed as kitchen workers, as are conductor Geoffrey Paterson and the five singers. Four of the singers are lined up along the red work surface of a Thai, Chinese, Vietnamese fast food restaurant, the name of which, The Golden Dragon, is emblazoned on the wall behind them. They match the way they stir, chop and whisk to the percussive introductory phrases in the orchestra. In front sits the fifth singer, wearing a t-shirt with a Coca-Cola logo, introduced as “A young Chinese man, beside himself with toothache,” otherwise referred to as The Little One. The exposition is clear, the design strong.

Having read through the libretto (helpfully supplied online by Music Theatre Wales) beforehand, I was concerned that it might be difficult to follow what was going on through the interlocking stories weaving through the central dilemma of What to Do about an illegal immigrant with toothache. On one level I need not have worried about that. The position of the singers in front of the ensemble, combined with their impeccable diction, meant everything was clearly audible.

However, this was a tricky course to weave, the 49 episodes of Schimmelpfennig’s stage play having been reduced to 21 for the opera. The performers having to switch from one character to another frequently was achieved effectively enough in Michael McCarthy’s production, but the strands of the different story lines – involving a Grandfather, pregnant Granddaughter, her Boyfriend and Hans the shopkeeper next door – did not always remain clearly differentiated. Maybe this would not have mattered had the central theme of the exploitation of the vulnerable come through strongly. Sadly, for me, it did not.

Part of the reason for this lies in the text and dramatis personae. Dramatic tension is difficult to achieve, because there is no personification of the oppression of the kitchen workers, no kitchen manager to chivvy them or for them to rail against. There are, instead, the characters of the cricket and the ant. In Aesop’s fable the foolish cricket sings instead of gathering grain for winter; the ant who she asks for food has no mercy. Here the story is much darker. The cricket, also representing the sister for whom The Little One is searching, is ruthlessly exploited by the ant and abused by The Grandfather, Hans and the Boyfriend.

The production was played for laughs, which sounds strange – neither toothache nor any form of exploitation being a laughing matter. Had it been a question of the laugh which dies in your throat when you realise the stark truth, this approach might have worked, but this was not the case. In fact, worse, the way the sexual exploitation of the cricket is portrayed is crude and a distinctly questionable use of farce. I question the use of the singers to portray the characters of the cricket and the ant. There are other options, the use of puppetry for example, through which the message might have come through in a less diluted form.

There is also the issue of the flight attendants, who come to the restaurant for a meal. The tooth which is eventually extracted from The Little One’s mouth flies through the air and lands in the Thai soup which one of the attendants has ordered. The attendants are observers – one of them refers to seeing an open boat full of people on the ocean as they flew over. Then The Waitress comes over and asks them if they would like something to drink. Not only is there no commentary (a limitation of the text) but the interaction with The Waitress is humorous (a dubious production decision). And why, just because the (female) attendants are played by men, do they have to be played as camp?

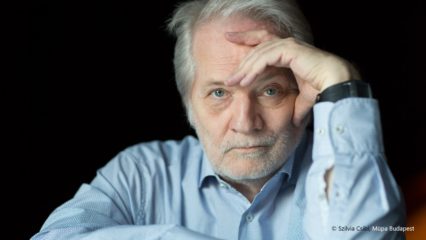

Having said all this, the performances of all concerned were excellent. The commitment of the singers was total, and in a strong ensemble mezzo Lucy Schaufer and tenor Andrew Mackenzie Wicks were stellar, both in terms of singing and acting. The instrumental ensemble played with verve and, in the few lyrical passages, sensitivity. Composer Peter Eötvös’s score is driven by the action and supports it admirably, with the sparky sonorities of a band weighted towards wind – including a contra bass clarinet – brass and percussion.

But the fact remains that for all that I enjoyed the music and the performances, I was disappointed. The subject matter is important, and while I am happy for laughter to play its part, I also want to cry, or at least be moved. I wasn’t, not one tiny bit. The outcome of the tooth extraction is tragic, but I did not feel it to be so. Consequently, the climax of the opera and what it had to say about the iniquities of human trafficking did not impact strongly on me.

One final doubt and question. It was an all-white cast. The central characters were Asian. I know that four of the singers had to play multiple roles, and that some of the other characters were (possibly) not Asian. But, I wonder if consideration was given to casting an Asian singer in at least the role of The Little One.

An opera by Peter Eötvös

Based on the play of the same name by Roland Schimmelpfennig

Music Theatre Wales

Conductor: Geoffrey Paterson

Director: Michael McCarthy

Designer: Simon Banham

Lighting Designer: Ace McCarron

Singers: Llio Evans, Lucy Schaufer, Andrew Mackenzie Wicks, Daniel Norman, Johnny Herford

Sherman Theatre, Cardiff, 22nd September 2017

Header photo: Andrew Mackenzie Wicks as the Cricket: credit Clive Barda/ArenaPAL

Cath Barton won the New Welsh Writing AmeriCymru Prize for the Novella with The Plankton Collector, which is published by New Welsh Review under their Rarebyte imprint. Her second novella, In the Sweep of the Bay, will be published by Louise Walters Books in September 2020, and in early 2021 Retreat West Books will publish her collection of short stories inspired by the work of the Flemish artist Hieronymus Bosch.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.